In this study, we investigate the contact characteristics of the planetary roller screw mechanism, a critical component for converting rotary motion into linear motion in high-precision applications such as aerospace, CNC machinery, and optical instruments. The planetary roller screw offers advantages like high load capacity, accuracy, and longevity, but its performance heavily depends on the contact behavior between threads. Previous research has simplified contact analysis by assuming coincident principal planes, which may introduce errors. Here, we employ differential geometry to compute principal curvatures and directions, derive the angle between principal planes, and analyze Hertzian contact effects. Our focus is on how structural parameters influence contact ellipse shape and area, providing insights for optimizing planetary roller screw designs.

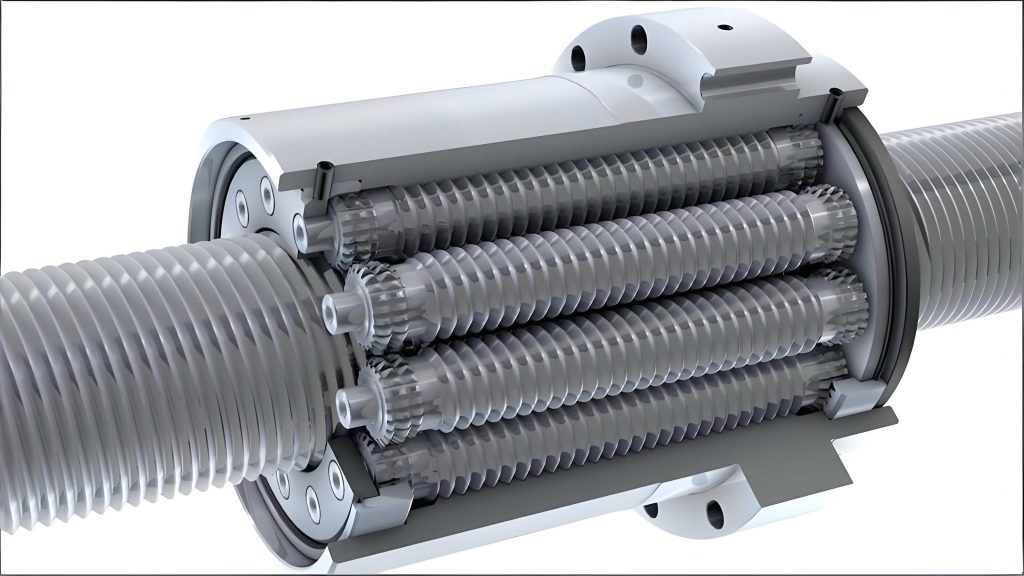

The planetary roller screw mechanism consists of a screw, multiple rollers, and a nut, with threaded surfaces in contact to transmit loads. Accurate contact modeling is essential for predicting stress, wear, and fatigue life. We build on existing work by incorporating the principal plane angle, often overlooked in simplifications. Using global coordinate systems and transformation matrices, we calculate this angle and integrate it into Hertz contact theory to determine ellipse eccentricity and area. Numerical examples illustrate the impact of pitch and thread profile half-angle, comparing results with simplified methods.

Geometric Foundation and Principal Curvatures

To analyze the contact in a planetary roller screw, we start with the parametric equations of the helical surfaces for the screw, roller, and nut. Based on the thread profile in the normal cross-section, the unified surface equation for each part is given by:

$$z_i = \xi h_i(r_{pi}) / \cos \lambda_i + l_i \theta_{pi} / (2\pi)$$

where \(i = s, r, n\) denotes screw, roller, and nut; \(\xi = \pm 1\) for upper or lower surfaces; \(h_i(r_{pi})\) is the profile equation in the normal section; \(l_i\) is the lead; and \(\lambda_i\) is the helix angle. The parametric form is:

$$\mathbf{f}_i = (r_{pi} \cos \theta_{pi}, r_{pi} \sin \theta_{pi}, \xi h_i(r_{pi}) / \cos \lambda_i + l_i \theta_{pi} / (2\pi))$$

The unit normal vector \(\mathbf{n}_i\) is derived from the gradient of the implicit surface equation. Using differential geometry, the first fundamental form coefficients \(E, F, G\) and second fundamental form coefficients \(L, M, N\) are computed as:

$$E = \mathbf{f}_{i,r} \cdot \mathbf{f}_{i,r}, \quad F = \mathbf{f}_{i,r} \cdot \mathbf{f}_{i,\theta}, \quad G = \mathbf{f}_{i,\theta} \cdot \mathbf{f}_{i,\theta}$$

$$L = \mathbf{f}_{i,rr} \cdot \mathbf{n}_i, \quad M = \mathbf{f}_{i,r\theta} \cdot \mathbf{n}_i, \quad N = \mathbf{f}_{i,\theta\theta} \cdot \mathbf{n}_i$$

where subscripts denote partial derivatives with respect to \(r_{pi}\) and \(\theta_{pi}\). The principal curvatures \(\kappa_1\) and \(\kappa_2\) are found from the mean curvature \(H\) and Gaussian curvature \(K\):

$$\kappa_1 = H + \sqrt{H^2 – K}, \quad \kappa_2 = H – \sqrt{H^2 – K}$$

$$H = \frac{EN – 2FM + GL}{2(EG – F^2)}, \quad K = \frac{LN – M^2}{EG – F^2}$$

The principal directions are obtained by solving:

$$\begin{vmatrix} E \, dr^2 + F \, dr \, d\theta & F \, dr^2 + G \, dr \, d\theta \\ L \, dr^2 + M \, dr \, d\theta & M \, dr^2 + N \, dr \, d\theta \end{vmatrix} = 0$$

yielding ratios \(dr : d\theta\). Transforming these into Cartesian coordinates gives the principal direction vectors \(\mathbf{t}_{i1}\) and \(\mathbf{t}_{i2}\) at the contact point.

Angle Between Principal Planes

The principal plane angle is crucial for accurate contact analysis in the planetary roller screw. We establish a global coordinate system aligned with the screw axis. For correct meshing, contact points must satisfy height matching conditions. For a screw with \(n_s\) starts (e.g., \(n_s = 5\)), the contact point angles \(\alpha_s, \alpha_{rs}, \alpha_{rn}, \alpha_n\) for screw, roller-screw side, roller-nut side, and nut are related by:

$$\alpha_{rs} = n_s \alpha_s, \quad \alpha_{rn} = \alpha_{rs} + \pi, \quad \alpha_n = \alpha_{rn} / n_s$$

Rotation matrices transform part-specific principal directions into the global system. The roller rotation matrix \(\mathbf{K}_r\) and nut rotation matrix \(\mathbf{K}_n\) are:

$$\mathbf{K}_r = \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\pi – 4\alpha_s) & -\sin(\pi – 4\alpha_s) & 0 \\ \sin(\pi – 4\alpha_s) & \cos(\pi – 4\alpha_s) & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \mathbf{K}_n = \begin{bmatrix} \cos(-\pi/5) & -\sin(-\pi/5) & 0 \\ \sin(-\pi/5) & \cos(-\pi/5) & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$$

For the roller-screw side, the principal planes are \([\mathbf{t}_{s1}, \mathbf{n}_s]\) and \([\mathbf{t}_{s2}, \mathbf{n}_s]\) for the screw, and \([\mathbf{K}_r \cdot \mathbf{t}_{rs1}, \mathbf{K}_r \cdot \mathbf{n}_{rs}]\) and \([\mathbf{K}_r \cdot \mathbf{t}_{rs2}, \mathbf{K}_r \cdot \mathbf{n}_{rs}]\) for the roller. The angle \(\omega_s\) between these planes is computed via vector algebra. Similarly, \(\omega_n\) is found for the roller-nut side. Our analysis shows that \(\omega_s\) and \(\omega_n\) remain constant during engagement, simplifying dynamic modeling.

Hertzian Contact Analysis

Under load, contact points deform into elliptical areas. According to Hertz theory, the semi-major axis \(a\) and semi-minor axis \(b\) of the ellipse are:

$$a = m_a \sqrt[3]{\frac{3Q}{2\Sigma \rho} \left( \frac{1 – \mu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \mu_2^2}{E_2} \right)}, \quad b = m_b \sqrt[3]{\frac{3Q}{2\Sigma \rho} \left( \frac{1 – \mu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \mu_2^2}{E_2} \right)}$$

where \(Q\) is the normal load, \(E_i\) and \(\mu_i\) are elastic moduli and Poisson’s ratios, \(\Sigma \rho\) is the sum of principal curvatures, and \(m_a, m_b\) are ellipse coefficients related to eccentricity \(e = \sqrt{1 – (b/a)^2}\). The coefficients depend on complete elliptic integrals \(K(e)\) and \(L(e)\):

$$m_a = \frac{2K(e)}{\pi \sqrt[3]{e^2}}, \quad m_b = \frac{2K(e) \sqrt{1 – e^2}}{\pi \sqrt[3]{e^2}}$$

The principal curvature function incorporates the principal plane angle \(\omega\):

$$F(\rho) = \frac{(\rho_{11} – \rho_{12})^2 + 2(\rho_{11} – \rho_{12})(\rho_{21} – \rho_{22}) \cos 2\omega + (\rho_{21} – \rho_{22})^2}{\Sigma \rho^2}$$

where \(\rho_{ij}\) are curvatures for bodies 1 and 2 in principal planes. Solving for \(e\) involves iterative methods using \(F(\rho)\) and material properties. This approach allows us to assess how \(\omega\) influences contact ellipse shape and stress distribution in the planetary roller screw.

Numerical Examples and Parametric Studies

We consider a standard planetary roller screw with parameters listed in Table 1. The screw has 5 starts, a pitch of 2 mm, and a thread profile half-angle of 45°. Using MATLAB, we compute principal curvatures, angles, and ellipse parameters.

| Parameter | Screw | Roller | Nut |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal radius \(r_i\) (mm) | 15 | 5 | 25 |

| Number of starts \(n_i\) | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Pitch \(p_i\) (mm) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Profile half-angle \(\beta_i\) (deg) | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Roller contour radius \(R_r\) (mm) | — | 7.0711 | — |

Table 2 compares results with and without considering the principal plane angle (\(\omega = 0\) vs. \(\omega \neq 0\)). The angle \(\omega\) significantly affects eccentricity \(e\), with errors up to 8.7% for pitch variations and 7.2% for half-angle changes. This highlights the importance of including \(\omega\) in planetary roller screw contact analysis.

| Contact Side | \(\omega\) (deg) | Eccentricity \(e\) (\(\omega = 0\)) | Eccentricity \(e\) (\(\omega \neq 0\)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roller-Screw | 48.4136 | 0.8258 | 0.8626 |

| Roller-Nut | 48.5240 | 0.8620 | 0.8179 |

We explore the impact of pitch and half-angle on \(\omega\) and \(e\). Figure 1 (based on computed data) shows that \(\omega\) increases linearly with pitch for both sides, but the roller-screw side plateaus at higher pitches. For half-angle, \(\omega\) decreases nonlinearly, with the roller-nut side showing a steeper decline. The eccentricity \(e\) varies non-monotonically; for instance, as pitch rises, \(e\) oscillates due to changes in curvature sums. These trends are summarized in Table 3 for select parameter values.

| Pitch \(p\) (mm) | Half-angle \(\beta\) (deg) | \(\omega_s\) (deg) | \(\omega_n\) (deg) | \(e_s\) | \(e_n\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 45 | 40.2 | 40.5 | 0.851 | 0.830 |

| 2.0 | 45 | 48.4 | 48.5 | 0.863 | 0.818 |

| 2.5 | 45 | 52.1 | 53.8 | 0.842 | 0.805 |

| 2.0 | 40 | 50.3 | 51.2 | 0.870 | 0.812 |

| 2.0 | 50 | 46.8 | 45.9 | 0.855 | 0.825 |

The contact ellipse area \(A = \pi a b\) under different loads is given by:

$$A = \pi m_a m_b \left( \frac{3Q}{2\Sigma \rho} \left( \frac{1 – \mu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \mu_2^2}{E_2} \right) \right)^{2/3}$$

Table 4 lists areas for loads from 100 N to 500 N, assuming steel parts (\(E = 210\) GPa, \(\mu = 0.3\)). Including \(\omega\) slightly increases area on the roller-screw side and decreases it on the roller-nut side, but differences are under 5%, indicating that \(\omega\) has a minor effect on area but a notable one on ellipse shape.

| Load \(Q\) (N) | Area \(A_s\) (mm², \(\omega = 0\)) | Area \(A_s\) (mm², \(\omega \neq 0\)) | Area \(A_n\) (mm², \(\omega = 0\)) | Area \(A_n\) (mm², \(\omega \neq 0\)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 0.152 | 0.158 | 0.148 | 0.143 |

| 200 | 0.241 | 0.250 | 0.235 | 0.227 |

| 300 | 0.312 | 0.324 | 0.304 | 0.294 |

| 400 | 0.373 | 0.387 | 0.364 | 0.352 |

| 500 | 0.427 | 0.443 | 0.417 | 0.403 |

Discussion on Structural Parameter Influences

Our analysis of the planetary roller screw reveals that the principal plane angle \(\omega\) remains constant during operation, simplifying dynamic models. However, ignoring \(\omega\) leads to significant errors in eccentricity prediction, which affects stress concentration and fatigue life. The non-linear relationship between pitch, half-angle, and \(e\) suggests that optimization requires careful balancing. For instance, increasing pitch improves load capacity but may alter ellipse shape, potentially increasing wear. Similarly, half-angle adjustments impact contact conformity and sliding behavior.

We derive additional formulas to quantify these effects. The curvature sum \(\Sigma \rho\) for the roller-screw side is:

$$\Sigma \rho = \kappa_{s1} + \kappa_{s2} + \kappa_{r1} + \kappa_{r2}$$

where \(\kappa\) values depend on thread geometry. The sensitivity of \(e\) to \(\omega\) can be expressed as:

$$\frac{de}{d\omega} \approx \frac{F'(\rho) \cdot \sin 2\omega}{2e \cdot (dK/de)/K(e)}$$

This derivative indicates that \(e\) changes most when \(\omega\) is near 45°, common in planetary roller screw designs. Furthermore, contact pressure \(p_0\) is related to ellipse dimensions by:

$$p_0 = \frac{3Q}{2\pi a b}$$

Thus, errors in \(a\) and \(b\) due to \(\omega\) neglect directly affect pressure estimates. Our results align with industry trends; for example, commercial planetary roller screw products often use pitches that minimize \(e\) variations, as seen in our data points marked in parametric studies.

Conclusion

In this work, we have presented a comprehensive analysis of contact characteristics in planetary roller screw mechanisms, emphasizing the role of the principal plane angle. By applying differential geometry and Hertz theory, we computed principal curvatures, derived the constant angle between principal planes, and evaluated ellipse parameters. Numerical examples show that neglecting this angle introduces errors up to 8.7% in eccentricity, while its effect on contact area is minor. Structural parameters like pitch and thread profile half-angle influence the angle and ellipse shape non-linearly, guiding design choices for enhanced performance. Future research could extend this approach to dynamic loading and thermal effects in planetary roller screw systems, further optimizing their reliability in high-precision applications.

The planetary roller screw remains a vital component in motion control, and accurate contact modeling is key to advancing its capabilities. Our methodology provides a foundation for more precise simulations and design optimizations, ensuring that planetary roller screw mechanisms continue to meet demanding engineering standards.