In my years of working with precision mechanical systems, I have come to appreciate the unique role that cycloidal drives play in various industrial applications. These reducers, known for their high torque density, compact design, and smooth operation, are critical components in robotics, conveyor systems, and heavy machinery. However, their performance and longevity are intimately tied to disciplined maintenance and proactive fault management. Through this article, I aim to share a comprehensive analysis grounded in practical experience, focusing on the operational principles, systematic maintenance routines, and effective troubleshooting strategies for cycloidal drives. I will employ formulas and tables to distill complex information into actionable knowledge, ensuring that practitioners can optimize the lifecycle of these remarkable devices.

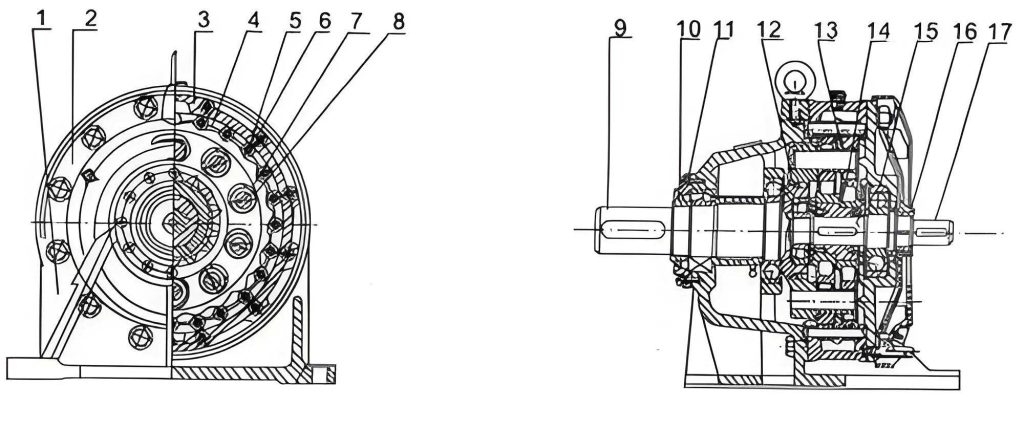

The fundamental operation of a cycloidal drive is a fascinating application of planetary kinematics. At its core, the mechanism converts high-speed, low-torque input into low-speed, high-torque output through a unique啮合 (meshing) action between a cycloidal disc and a ring of stationary pin gears. The input shaft drives an eccentric cam or a dual eccentric sleeve with a 180-degree phase shift. This eccentric motion is transferred to one or two cycloidal discs via roller bearings, often called turning arm bearings, forming an H-type mechanism. The lobes of the cycloidal disc then engage with the pins of the stationary ring gear.

The kinematics can be described mathematically. As the input shaft rotates once, the eccentric sleeve causes the cycloidal disc to undergo a复合运动 (compound motion): a revolution around the center (公转) and a slight rotation about its own center (自转). For a single-stage cycloidal drive, the speed reduction ratio \( i \) is determined by the difference between the number of pins \( Z_p \) on the stationary ring and the number of lobes \( Z_c \) on the cycloidal disc. The standard formula is:

$$ i = -\frac{Z_p}{Z_p – Z_c} $$

Typically, \( Z_c = Z_p – 1 \), leading to a high reduction ratio \( i = -Z_p \). The negative sign indicates a reversal in the direction of rotation between the input and the output. The output motion is extracted via a set of rollers or pins in an output mechanism (often a W-output机构) that captures the slow rotation of the cycloidal disc while canceling its eccentric oscillation. The torque capacity is exceptionally high due to the multiple lobes sharing the load simultaneously. The force transmission can be analyzed by considering the contact forces between the cycloidal profile and the pins. The theoretical contact stress \( \sigma_H \) at the pin-cycloid interface can be estimated using a modified Hertzian contact formula for cylindrical surfaces:

$$ \sigma_H = \sqrt{\frac{F_n E^*}{\pi \rho L}} $$

where \( F_n \) is the normal force per contact, \( E^* \) is the effective elastic modulus \( \left(\frac{1}{E^*}=\frac{1-\nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1-\nu_2^2}{E_2}\right) \), \( \rho \) is the effective radius of curvature, and \( L \) is the contact length. Proper lubrication is crucial to mitigate this stress. The efficiency \( \eta \) of a well-maintained cycloidal drive is high, often above 90%, and can be modeled accounting for sliding and rolling friction losses:

$$ \eta \approx 1 – \left( \frac{\mu_s P_s + \mu_r P_r}{P_{in}} \right) $$

where \( \mu_s \) and \( \mu_r \) are coefficients for sliding and rolling friction, \( P_s \) and \( P_r \) are the respective power losses, and \( P_{in} \) is the input power.

To systematically outline the maintenance requirements for a cycloidal drive, I have found that a tabular approach is invaluable. The following table summarizes the core maintenance activities, their frequency, and key parameters. Adherence to this schedule is non-negotiable for reliable operation.

| Maintenance Activity | Initial / Frequency | Key Parameters & Notes | First-Person Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Oil Change | After first 100 operating hours | Flush internal cavity thoroughly to remove manufacturing residues and wear-in debris. | I always use a mild flushing oil and inspect the drained oil for any unusual metallic particles. |

| Routine Oil Changes | Every 6 months (for 8h/day operation). Adjust to 3-5 months for >8h/day or harsh conditions (dust, high temp, moisture). | Oil type: ISO VG 220-320 synthetic or mineral gear oil recommended by manufacturer. Check oil specification for extreme temperatures. | In my practice, logging the operating hours is more accurate than calendar time. I use a simple hour meter. |

| Oil Level Inspection | Weekly / Before each start-up in critical applications | Maintain level between min/max marks on sight glass or dipstick. Overfilling can cause overheating and seal leakage. | A sudden drop in oil level often indicates a seal failure. Investigate immediately. |

| Bolt Tightening Check | Monthly, especially for first 6 months after installation | Check all foundation, flange, and coupling bolts. Torque to manufacturer’s specification (e.g., 70-90 Nm for M12 bolts). | I follow a star-pattern tightening sequence for flange bolts to ensure even pressure. |

| Alignment Check (Coupling) | Quarterly, or after any base modification | Check parallel and angular misalignment. Tolerance typically <0.05mm offset and <0.05°/100mm angular. | Misalignment is a silent killer. I use dial indicators, not just straight edges, for precision. |

| Temperature Monitoring | Continuous via sensor or periodic manual checks | Normal operating temperature: 40-70°C. Ambient temperature +50°C is a good rule of thumb. Alarm at 80°C, shutdown at 90°C. | I feel the housing with the back of my hand; a sudden hot spot often points to a bearing issue. |

| Vibration & Noise Audit | Monthly listening and annual formal vibration analysis | Baseline vibration velocity (e.g., <4.5 mm/s RMS). Unusual clicking, grinding, or rhythmic knocking needs investigation. | Stethoscopes are cheap and incredibly effective for localizing internal sounds. |

| Seal Inspection | During every oil change | Look for oil leaks, hardened/cracked rubber on shaft seals. Replace if any sign of wear or leakage. | When replacing seals, I always clean the shaft sleeve surface to prevent new seal damage. |

Beyond the schedule, the philosophy of maintaining a cycloidal drive involves understanding its “personality.” The lubrication regime is paramount. The oil does not just reduce friction; it carries away heat, protects against corrosion, and helps flush out microscopic wear particles. I strictly use oils with anti-wear (AW) and extreme pressure (EP) additives suitable for hypoid gears, as the contact in a cycloidal drive can be similarly demanding. The replenishment volume \( V \) for a given housing can be estimated, but one must always refer to the manual:

$$ V = k \cdot (A \cdot L) $$

where \( A \) is the internal cross-sectional area, \( L \) is the housing length, and \( k \) is a fill factor (typically 0.7-0.8). More critically, I never mix different oil brands or types without a compatibility test.

Another aspect I emphasize is the systematic inspection of internal components during major overhauls. When disassembling a cycloidal drive for inspection, I follow a meticulous process. After draining the oil and removing the housing, the first component I assess is the set of needle rollers and the pin gear. Wear patterns here tell a story. Uniform polishing is normal, but pitting, spalling, or brinelling indicates overloading or lubrication failure. The clearance between the cycloidal disc lobes and the pins is critical; excessive clearance leads to backlash and impact loads. A simple jig can be used to measure the backlash \( B \):

$$ B = \frac{\Delta \theta_{output}}{i} $$

where \( \Delta \theta_{output} \) is the angular free movement at the output shaft when the input is locked. Backlash should typically be less than 10 arcminutes for precision applications. When reassembling, the preload on the eccentric bearings is crucial. Too little causes play, too much generates excessive heat. The bearing preload force \( F_{preload} \) is often set via shims and should follow:

$$ F_{preload} = C \cdot \sqrt[3]{\frac{d^2}{D}} $$

where \( C \) is a bearing constant, \( d \) is bore diameter, and \( D \) is outer diameter. Manufacturer guidelines always take precedence.

Despite best maintenance practices, faults in cycloidal drives can and do occur. A structured approach to fault analysis is essential. From my experience, faults can be categorized into mechanical wear, lubrication failures, assembly errors, and overload events. The following table details common faults, their root causes, diagnostic symptoms, and recommended corrective actions.

| Fault Category | Specific Fault | Primary Root Causes | Typical Symptoms | Corrective Action & First-Person Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bearing & Wear | Eccentric/Turning Arm Bearing Failure | Insufficient or degraded lubrication, contamination (dust, water), misalignment, excessive axial load. | Rising temperature localized near input side, grinding noise synchronous with input speed, increased vibration at bearing frequencies. | Replace the entire bearing set. I never replace just one bearing in a paired set. Clean the housing meticulously before installation. Investigate and rectify the root lubrication or alignment issue. |

| Pin (Needle) Bearing or Pin Gear Wear | Abrasive wear from contaminated oil, fatigue from shock loads, improper heat treatment of components. | Increased backlash, metallic particles in oil, possible knocking sound during load reversal. | Replace worn pins and the pin gear segment or entire ring. For the cycloidal drive to function smoothly, all pins must be replaced as a set to maintain uniform load distribution. | |

| Cycloidal Disc Lobe Wear or Pitting | Overload beyond rated capacity, inadequate lubrication film, foreign object damage. | Localized scoring on disc lobes, possible seizure marks, noise during specific phase of rotation. | Replace the cycloidal disc(s). Always replace as a matched pair if two discs are used. Check the corresponding pin gear for damage. | |

| Lubrication Failure | Oil Degradation & Sludge Formation | Oxidation due to high temperature, prolonged service interval, ingress of moisture or process chemicals. | Dark, viscous, or milky oil, strong burnt smell, reduced heat dissipation leading to general overheating. | Complete oil flush and refill with fresh, recommended oil. Identify and eliminate heat source or contaminant ingress point. Consider synthetic oil for higher temperature stability. |

| Oil Leakage | Shaft seal failure (aging, wear, improper installation), overfilling, blocked breather causing pressure buildup. | Oil seepage around input/output shafts, oil accumulation on housing or floor. | Replace shaft seals. Ensure breather is clean and functional. Verify oil level is correct, not above max mark. | |

| Structural & Fastener | Keyway Damage (Eccentric Sleeve or Output Shaft) | Frequent starts/stops (shock torsional loads), improper fit between key and keyway, material fatigue. | Abnormal knocking on startup, visible fretting or deformation at keyway, eventual loss of drive. | Option 1: Replace the damaged component (eccentric sleeve or shaft). Option 2: For emergency repair, machine a new keyway at 180 degrees from the damaged one. I prefer replacement for long-term reliability. Ensure key is properly sized and fitted. |

| Housing Crack or Bolt Failure | Severe shock load, foundation settlement, corrosion, improper bolt tightening sequence or torque. | Visible crack, oil leak from crack, loose housing parts, abnormal structural vibration. | Weld repair may be possible for non-critical housing areas, but often housing replacement is needed. Replace all fasteners in the affected area and retorque to spec. | |

| Coupling Misalignment | Foundation shift, thermal growth not accounted for, improper installation. | High vibration at 1x and 2x running speed, coupling overheating, premature bearing failure on connected equipment. | Realign drive to driven equipment using laser or dial indicator tools. Re-check alignment after running under thermal equilibrium. | |

| Operational | Overheating (General) | Overload, high ambient temperature, incorrect oil viscosity, blocked cooling fins, failed cooling fan. | Housing temperature >80°C, thermal protector tripping, possible smoke or smell. | Immediately reduce load if possible. Check ambient conditions, oil level and viscosity. Clean cooling surfaces. Install auxiliary cooling if needed. The steady-state temperature rise \( \Delta T \) can be modeled: \( \Delta T \approx \frac{P_{loss}}{h \cdot A} \), where \( P_{loss} \) is power loss, \( h \) is heat transfer coefficient, \( A \) is surface area. |

| Performance | Excessive Backlash or Lost Motion | Cumulative wear in pins, cycloid disc, and output mechanism bearings, improper assembly clearance. | Poor positional accuracy in servo applications, “wind-up” before motion, clunking noise during direction change. | Measure backlash systematically. Replace worn components starting with the output mechanism rollers/pins. Adjust preload shims if design allows. For precision cycloidal drives, backlash can sometimes be compensated in the controller, but mechanical rectification is preferred. |

Diagnosing a faulty cycloidal drive often starts with sensory observations. I recall an instance where a drive exhibited a high-pitched whine accompanied by a gradual temperature rise. Spectral analysis of vibration data revealed a dominant frequency at the cage pass frequency of the eccentric bearing, pointing to lubricant starvation. The corrective action was an oil change and bearing replacement, but the root cause was a slightly undersized breather that became clogged in a dusty environment, causing a vacuum that impeded oil flow to the bearings. This highlights the need for a holistic view.

Mathematical modeling can also aid in fault prediction. For example, the remaining useful life (RUL) of the eccentric bearings, often the first point of failure, can be estimated using a modified Lundberg-Palmgren bearing life equation, adjusted for the specific loading in a cycloidal drive:

$$ L_{10} = \frac{10^6}{60 \cdot n} \left( \frac{C}{P_{eq}} \right)^p $$

where \( L_{10} \) is the rated life in hours (90% reliability), \( n \) is input speed (rpm), \( C \) is the dynamic load rating, \( P_{eq} \) is the equivalent dynamic load on the bearing, and \( p \) is 3 for ball bearings and 10/3 for roller bearings. In a cycloidal drive, \( P_{eq} \) must account for the combined radial load from the cycloidal disc reaction forces and the centrifugal force from the eccentric mass:

$$ P_{eq} = X \cdot F_r + Y \cdot F_a $$

where \( F_r \) and \( F_a \) are radial and axial loads, and \( X, Y \) are factors from bearing tables. Monitoring vibration trends and temperature allows for dynamic updating of this life estimate, moving from time-based to condition-based maintenance for the cycloidal drive.

When it comes to repair, part matching is critical. The precise conjugate action of the cycloidal profile and the pins means that components from different manufacturers or even different production batches from the same maker may not mesh correctly. I always insist on using genuine spare parts or parts from a certified rebuilder. If a component like the eccentric sleeve must be machined locally, material selection is paramount. I recommend case-hardening steels like AISI 8620 or similar, followed by carburizing and grinding to achieve the required hardness (58-62 HRC on the surface) and precision. The eccentricity \( e \) must be held to a tolerance of ±0.005mm, as it directly affects the backlash and smoothness of the cycloidal drive.

Preventive measures are the cornerstone of reliability. Implementing a robust maintenance program for cycloidal drives involves not just following a checklist but understanding the interdependencies. For instance, ensuring perfect alignment reduces bearing load, which in turn lowers operating temperature, which then extends oil life and seal integrity—a virtuous cycle. I advocate for the use of condition monitoring tools: simple infrared thermometers, vibration pens, and periodic oil analysis. Oil analysis can detect wear metals (Fe, Cu from gears and bearings), silicon (dust ingress), and water content long before a catastrophic failure.

In conclusion, the reliable operation of a cycloidal drive is a testament to the marriage of elegant mechanical design and disciplined engineering practice. From my firsthand experience, treating the cycloidal drive not as a black box but as a system whose physics I understand has been the key to maximizing uptime and productivity. The principles of timely lubrication, precise alignment, careful handling of components, and systematic fault diagnosis are universal. By integrating the quantitative guidelines provided through formulas and the qualitative insights summarized in tables, maintenance personnel can develop an intuitive feel for these machines. The goal is to transform maintenance from a reactive cost center into a proactive strategy that fully leverages the high torque, compactness, and durability that make the cycloidal drive such a valuable asset in modern industry. Ultimately, every hour invested in understanding and caring for a cycloidal drive pays dividends in reduced downtime, lower lifecycle costs, and smoother, more predictable production flows.