In modern facility agriculture, the cultivation of vegetables often relies on plug seedling transplanting to enable large-scale management and production. Approximately 60% of vegetables in China are grown using this method. During the seedling cultivation process, thinning transplanting—where seedlings are moved from high-density plug trays to low-density ones—is a critical step to provide optimal growing conditions and enhance yield. However, this process is predominantly manual, leading to inefficiencies, high labor costs, and risks of seedling damage. Automating thinning transplanting is essential for improving precision and productivity in agricultural operations. This article presents the design and experimental validation of an adjustable spacing end effector based on a cylindrical cam mechanism, aimed at addressing these challenges. The end effector is capable of performing thinning transplanting between plug trays of different specifications, thereby increasing automation and reducing seedling injury.

The core of any automated transplanting system is the end effector, which directly interacts with the seedlings. Previous research on transplanting end effectors has focused on single-seedling operations, with limited attention to multi-seedling handling or adjustable spacing for thinning purposes. Existing multi-seedling end effectors are often complex and tailored to specific tray sizes, lacking versatility. Meanwhile, commercial transplanting devices from countries like the United States and Australia are cost-prohibitive for widespread adoption in domestic markets. Therefore, we developed a novel end effector that integrates a cylindrical cam for spacing adjustment, allowing it to adapt to various plug tray configurations commonly used in facility agriculture, such as 128-cell, 72-cell, and 50-cell trays. This end effector design prioritizes simplicity, reliability, and minimal seedling damage during operation.

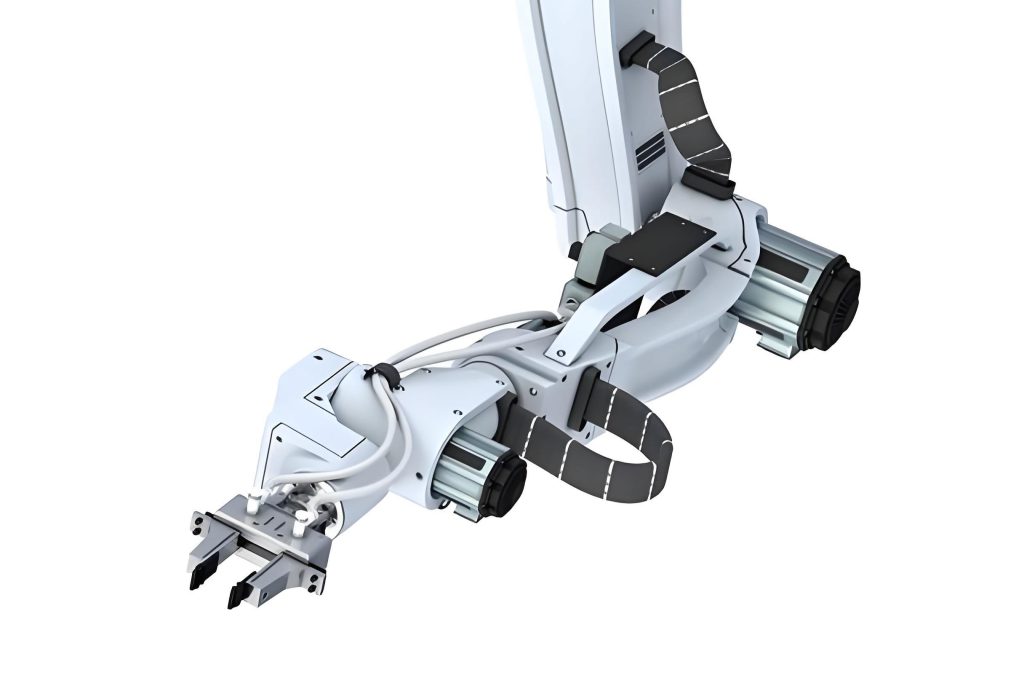

The overall structure of the adjustable spacing end effector comprises several key components: a stepper motor, frame, cylindrical cam, universal ball bearings, fixed plate, linear guide pair, and pen-shaped cylinders. The cylindrical cam is mounted on the frame via a diamond bearing seat, forming a revolute pair. The stepper motor drives the cam to rotate, adjusting the distance between two seedling-gripping fingers. Universal ball bearings, attached to the fixed plate, act as followers within the cam grooves. The linear guide pair, consisting of rails and sliders, ensures smooth linear motion of the fixed plate. The seedling-gripping fingers, located beneath the frame, include pen-shaped cylinders, seedling guard plates, and seedling needles. Each finger features dual needles that insert into the seedling plug at an angle when activated by the cylinders. This design minimizes leaf damage and enhances gripping stability.

The working principle of the end effector involves a sequence of steps: First, the end effector moves to the source plug tray, with the spacing between fingers adjusted to match the tray specification via cam rotation. Second, it descends to the picking height, aligning the needle tips with the plug surface at a specific entry angle. Third, the pen-shaped cylinders extend, driving the needles into the plug along the edge of the cell hole. Fourth, the end effector ascends vertically, extracting the seedling plug by overcoming adhesive forces from the cell wall. Fifth, the end effector transports the seedlings to the target tray while the cam adjusts the spacing to the new specification. Finally, the cylinders retract, releasing the seedlings into the target cells. This process ensures efficient and gentle handling, crucial for seedling survival post-transplant.

Designing the key components required careful theoretical analysis. The spacing adjustment mechanism centers on the cylindrical cam, which converts rotary motion into linear displacement of the followers. The cam was designed to accommodate a spacing adjustment range of 25–50 mm, covering common plug tray specifications. The cam rise is set at 12.5 mm, with a diameter of 25 mm and groove dimensions of 12 mm wide and 5 mm deep to fit Ф12 mm universal ball bearings. The cam profile curve was derived using simple harmonic motion to ensure smooth operation and minimize vibrations. The displacement equation is given by:

$$ s = 6.25 \left(1 – \cos \frac{x}{10}\right) \quad (0 \leq x \leq 20\pi) $$

where \( s \) is the displacement in mm, and \( x \) is the independent variable. This curve provides continuous and smooth motion, though practical conditions may introduce minor shocks. Dynamic simulations in Adams software verified the cam’s performance under different thinning requirements, such as transitioning from 72-cell to 50-cell trays. The simulations showed that the maximum contact stresses remained within allowable limits for the materials used, confirming structural integrity. For instance, the maximum acceleration during spacing change was around 7.59 m/s², with a maximum contact stress of 10.73 MPa, well below the yield strength of the polymer resin and stainless steel components.

Force analysis of the cylindrical cam mechanism ensures reliable operation. During spacing adjustment, the cam groove exerts forces on the followers. The equilibrium equations, based on d’Alembert’s principle, are:

$$ \begin{cases}

N \cos \gamma – F_k – f \sin \gamma = 0 \\

T – N \sin \gamma – f \cos \gamma = 0 \\

f = \mu N \\

F_k = f’ = \mu’ G

\end{cases} $$

where \( N \) is the normal force from the cam groove, \( F_k \) is the force to overcome friction in the linear guide, \( f \) is the friction force between the cam and follower, \( T \) is the motor-applied torque, \( \gamma \) is the angle between \( N \) and the cam axis, \( \mu \) and \( \mu’ \) are friction coefficients, and \( G \) is the total weight supported by the guide. Solving these equations yields the required motor torque. For a maximum weight \( G = 4.55 \, \text{N} \), the maximum torque \( M_{\text{max}} \) was calculated as 14.76 N·mm. Additionally, the maximum pressure angle \( \phi_{\text{max}} \) must satisfy \( \phi_{\text{max}} \leq [\phi] = 30^\circ \). Using the formula:

$$ \phi_{\text{max}} = \arctan \left( \frac{h}{r_m \sigma} \right) $$

where \( h = 12.5 \, \text{mm} \), \( r_m = 10 \, \text{mm} \), and \( \sigma \) is the equivalent friction angle (14.03°), we obtained \( \phi_{\text{max}} = 5.1^\circ \), meeting the design requirement.

The seedling-gripping fingers are critical for successful plug extraction. Each finger uses four flat needles inserted into one side of the plug, leveraging an entry angle and needle inclination to enhance extraction force while minimizing damage. Key parameters include the needle root opening \( d_1 \), needle tip opening \( d_2 \), needle included angle \( \alpha \), entry angle \( \beta \), insertion edge distance \( \varepsilon \), needle length \( l \), and needle spacing \( d_3 \). These parameters were optimized based on plug tray dimensions. For example, to avoid damaging cell walls, the conditions are:

$$ d_1 < l_1, \quad d_2 < l_2 $$

where \( l_1 \) and \( l_2 \) are the upper and lower side lengths of the cell hole. For 72-cell trays, \( l_1 = 40 \, \text{mm} \) and \( l_2 = 22 \, \text{mm} \); for 128-cell trays, \( l_1 = 30 \, \text{mm} \) and \( l_2 = 13 \, \text{mm} \). We set \( d_1 = 28 \, \text{mm} \). The needle included angle must satisfy:

$$ \alpha \geq \arctan \left( \frac{l_1 – l_2}{2h_k} \right) = \theta $$

where \( h_k \) is the cell height and \( \theta \) is the cell wall inclination angle (11.2° for 72-cell, 11.9° for 128-cell). The entry angle \( \beta \) is constrained between minimum and maximum values to prevent needle penetration through the cell wall. The minimum \( \beta_{\text{min}} = 90^\circ – \theta \), while the maximum \( \beta_{\text{max}} \) depends on geometric relations involving insertion depth \( h_z \). The needle length must ensure \( h_z \leq h_k \) to avoid piercing the tray bottom. Needle spacing \( d_3 \) is optimized to provide sufficient gripping force without excessive plug deformation.

To evaluate the end effector’s performance, we conducted coupling simulations using EDEM and RecurDyn software. A root-soil composite model of the seedling plug was developed based on CT scans of 25-day-old tomato seedlings. The plug matrix was modeled as spherical particles with radius 0.6 mm, using the EEPA contact model to account for cohesive forces due to moisture. The simulation replicated the needle insertion and extraction process, with single-factor tests examining the effects of needle included angle \( \alpha \), entry angle \( \beta \), and needle spacing \( d_3 \) on plug deformation. Deformation was measured as the change in plug upper side length and edge length after extraction. The simulation results are summarized in the table below:

| Factor | Levels | Optimal Range | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Needle Included Angle \( \alpha \) | 10°, 11°, 12°, 13°, 14° | 10°–12° | Larger angles increase plug deformation due to greater needle spread. |

| Entry Angle \( \beta \) | 0°, 3°, 6°, 9°, 12° | 4°–6° | Extreme angles cause significant deformation; moderate angles balance grip and damage. |

| Needle Spacing \( d_3 \) | 2 mm, 4 mm, 6 mm, 8 mm, 10 mm | 4–8 mm | Spacing below 4 mm or above 8 mm leads to high deformation from insufficient grip or excessive disturbance. |

The simulations indicated that plug deformation is minimized when \( \alpha \) is 10°–12°, \( \beta \) is 4°–6°, and \( d_3 \) is 4–8 mm. For instance, at \( \alpha = 10° \), deformation was around 1.28 mm, while at \( \alpha = 14° \), it increased to 1.90 mm. These findings guided the subsequent experimental design.

We constructed a transplanting test platform to validate the end effector under real conditions. Tomato seedlings (variety “Luyang k9”) aged 18 days were used, with plug parameters including height (95.33–112.47 mm), stem diameter (2.23–3.08 mm), and moisture content (51.90–67.22%). The platform incorporated the adjustable spacing end effector, a robotic arm for movement, and control systems. Orthogonal experiments were conducted with four factors: needle included angle \( \alpha \), entry angle \( \beta \), needle spacing \( d_3 \), and spacing change speed \( v \). Each factor had three levels, as shown in the table below:

| Factor | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \alpha \) (°) | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| \( \beta \) (°) | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| \( d_3 \) (mm) | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| \( v \) (mm/s) | 5 | 10 | 15 |

The response variables were maximum plug deformation \( \delta \) (mm) and transplanting success rate \( \eta \) (%). Success was defined as seedlings retaining over 70% of their original mass after transplanting and surviving for 10 days. Each test group involved 30 seedlings, repeated three times. The orthogonal array and results are summarized as follows:

| Test No. | \( \alpha \) (°) | \( \beta \) (°) | \( d_3 \) (mm) | \( v \) (mm/s) | \( \delta \) (mm) | \( \eta \) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1.66 | 80.00 |

| 2 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 3.42 | 70.00 |

| 3 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 15 | 2.29 | 73.33 |

| 4 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 2.95 | 67.77 |

| 5 | 11 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 3.27 | 83.33 |

| 6 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 1.24 | 56.67 |

| 7 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 2.67 | 90.00 |

| 8 | 12 | 5 | 4 | 15 | 4.79 | 63.33 |

| 9 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 1.84 | 63.33 |

Range analysis was performed to determine the influence of each factor on the responses. For plug deformation \( \delta \), the primary and secondary order of factors is: entry angle \( \beta \), spacing change speed \( v \), needle included angle \( \alpha \), needle spacing \( d_3 \). The mean deformations for each factor level are:

$$ \bar{\delta}_{\alpha1} = 2.46 \, \text{mm}, \quad \bar{\delta}_{\alpha2} = 2.49 \, \text{mm}, \quad \bar{\delta}_{\alpha3} = 3.10 \, \text{mm} $$

$$ \bar{\delta}_{\beta1} = 2.42 \, \text{mm}, \quad \bar{\delta}_{\beta2} = 3.83 \, \text{mm}, \quad \bar{\delta}_{\beta3} = 1.79 \, \text{mm} $$

$$ \bar{\delta}_{d31} = 2.56 \, \text{mm}, \quad \bar{\delta}_{d32} = 2.74 \, \text{mm}, \quad \bar{\delta}_{d33} = 2.74 \, \text{mm} $$

$$ \bar{\delta}_{v1} = 2.26 \, \text{mm}, \quad \bar{\delta}_{v2} = 2.44 \, \text{mm}, \quad \bar{\delta}_{v3} = 2.95 \, \text{mm} $$

The ranges are \( R_\alpha = 0.64 \), \( R_\beta = 2.04 \), \( R_{d3} = 0.18 \), \( R_v = 0.69 \), confirming that \( \beta \) has the greatest effect. For success rate \( \eta \), the order is: needle spacing \( d_3 \), entry angle \( \beta \), spacing change speed \( v \), needle included angle \( \alpha \). The mean success rates are:

$$ \bar{\eta}_{\alpha1} = 74.44\%, \quad \bar{\eta}_{\alpha2} = 69.26\%, \quad \bar{\eta}_{\alpha3} = 72.22\% $$

$$ \bar{\eta}_{\beta1} = 79.26\%, \quad \bar{\eta}_{\beta2} = 72.22\%, \quad \bar{\eta}_{\beta3} = 64.44\% $$

$$ \bar{\eta}_{d31} = 66.67\%, \quad \bar{\eta}_{d32} = 67.03\%, \quad \bar{\eta}_{d33} = 82.22\% $$

$$ \bar{\eta}_{v1} = 75.55\%, \quad \bar{\eta}_{v2} = 72.22\%, \quad \bar{\eta}_{v3} = 68.14\% $$

With ranges \( R_\alpha = 5.18 \), \( R_\beta = 14.82 \), \( R_{d3} = 15.55 \), \( R_v = 7.41 \). The optimal combination for minimizing deformation is \( \alpha1\beta3d3v1 \) (i.e., \( \alpha = 10^\circ \), \( \beta = 6^\circ \), \( d_3 = 4 \, \text{mm} \), \( v = 5 \, \text{mm/s} \)), while for maximizing success rate it is \( \alpha1\beta1d3v1 \) (\( \alpha = 10^\circ \), \( \beta = 4^\circ \), \( d_3 = 8 \, \text{mm} \), \( v = 5 \, \text{mm/s} \)). Considering both criteria, we selected \( \alpha = 10^\circ \), \( \beta = 4^\circ \), \( d_3 = 8 \, \text{mm} \), \( v = 5 \, \text{mm/s} \) as the best compromise, as it offers high success with acceptable deformation.

Verification tests were conducted under this optimal parameter set for two thinning scenarios: transplanting from 128-cell to 72-cell trays, and from 72-cell to 50-cell trays. Sixty tomato seedlings were used in total. The results showed that the average maximum plug deformation for 128-cell seedlings was \( 1.13 \pm 0.68 \, \text{mm} \), and for 72-cell seedlings was \( 1.51 \pm 0.64 \, \text{mm} \). The overall transplanting success rate was 93.33%, with a system efficiency of 22 seedlings per minute. All successfully transplanted seedlings survived the 10-day observation period. The deformation patterns observed in practice aligned with simulation predictions, validating the coupled EDEM-RecurDyn model. Failures were attributed mainly to positioning errors during needle insertion or poor root development in some plugs, leading to excessive soil shedding.

In conclusion, this study developed an adjustable spacing end effector for plug seedling thinning transplanting, leveraging a cylindrical cam mechanism for versatile spacing adjustment. The end effector design integrates theoretical analysis, dynamic simulation, and experimental optimization to achieve high performance. Key findings include the optimal parameters for needle geometry and operation speed, which minimize plug deformation and maximize transplanting success. The end effector proved effective across different tray specifications, with a success rate over 93% and efficient operation. This work provides a foundation for advancing automated thinning transplanting technology in facility agriculture, offering a cost-effective and adaptable solution. Future research could focus on enhancing the end effector’s intelligence, such as integrating vision systems for real-time seedling detection and adaptive control, further improving precision and robustness in diverse agricultural environments.