In the context of a rapidly aging society, the issue of elderly care, particularly for those living alone, has become a pressing social concern. The accelerated pace of urban life often leaves younger generations with limited time to spend with their aging parents, creating a significant emotional and safety vacuum. This situation has catalyzed a growing demand for intelligent products that offer companionship and monitoring. As robotic technology matures, companion robots characterized by ease of operation, learning, and interaction have emerged as a favored solution for the elderly market. This paper explores the application of user experience (UX) design principles to the development of an elderly companion robot. By analyzing existing challenges and conducting a structured investigation into user needs, I aim to define a design framework that prioritizes the well-being of the elderly user. The process involves establishing a hierarchical model of user requirements, performing a quantitative weight analysis to prioritize these needs, and translating the results into concrete product design principles for form, function, and interaction. The final design practice demonstrates how a human-centered approach can yield a companion robot that is not only functional but also emotionally resonant and easy to use, thereby providing a valuable reference for innovation in this field.

Understanding User Experience in the Context of Elderly Care

User Experience (UX) encompasses the holistic perceptions and responses a person has as a result of the use or anticipated use of a product, system, or service. It is a subjective, largely affective experience stemming from interaction with both physical and digital entities. Given its subjective nature, designing for positive UX requires identifying common patterns across a user base while allowing for personalization. A foundational framework for understanding UX was proposed by psychologist Donald Norman, who delineated three levels: the Visceral (instinctive reactions to appearance), Behavioral (pleasure and effectiveness of use), and Reflective (intellectualization and personal meaning). This framework underscores a “human-centered” design philosophy, where the core objectives are usability, safety, and fulfilling user needs and psychological states. Integrating UX design into the development of an elderly companion robot necessitates a deep focus on the unique physiological and psychological realities of the target users. The goal is to facilitate a positive interaction that addresses loneliness, supports independent living, and ultimately enhances the quality of daily life for the elderly.

Hierarchical Analysis of Target User Needs

The primary user group for this companion robot is defined as individuals aged 55 and above, who live alone, often with children working away from home. To thoroughly understand their needs, a mixed-methods approach was employed, including separate questionnaires for elderly individuals and their adult children, as well as field interviews and observations. The synthesized findings are categorized below.

Needs of the Children (Secondary Users)

Analysis of 150 questionnaire responses from adult children revealed predominant concerns. A significant majority (73%) expressed primary worry about their parents’ physical health and safety, fearing emergencies that might go unnoticed. Furthermore, 65% acknowledged that their elderly parents have a strong desire for conversation and reminiscence, an area where the children themselves feel they lack sufficient time. A notable portion (15%) had direct family experience with Alzheimer’s disease, heightening their focus on safety monitoring. Consequently, the needs from the children’s perspective cluster around remote companionship facilitation, real-time monitoring, and emergency alert systems.

Physiological Needs of the Elderly (Primary Users)

Aging naturally leads to the degeneration of various bodily functions. Common age-related changes include the onset of conditions like diabetes or arthritis, declining memory, reduced learning capacity, presbyopia (farsightedness), and diminished hearing. Research indicates that approximately 77% of people experience presbyopia around age 50. Therefore, the physiological demands placed on a companion robot center on compensating for these changes: simplified operation, health parameter monitoring, and proactive reminders for medication, appointments, or daily tasks.

Psychological Needs of the Elderly (Primary Users)

The psychological landscape of a solo-living elderly person is complex. Lack of regular family contact often breeds profound loneliness and a sense of being misunderstood. Concurrently, physical decline can foster feelings of inadequacy and vulnerability. This vulnerability may manifest as heightened sensitivity or stubbornness, as reported by 85% of the children surveyed. Beyond mere conversation, there is a deep need for empathy, emotional support, and mental stimulation. A companion robot should, therefore, address these layers by providing empathetic companionship, offering entertainment, helping cultivate new interests, and broadening their connection to the outside world to foster a more positive and engaged outlook.

Based on this tripartite analysis, I constructed a hierarchical model of user needs. The top tier represents the overarching goal: an optimal companion robot experience. The second tier decomposes into the three core need clusters identified. This model is summarized in the table below.

| Tier 1: Overall Goal | Tier 2: Core Need Clusters | Specific Need Manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized Companion Robot Experience for the Elderly | Needs of the Children (Caregivers) | Remote communication, Safety monitoring, Emergency alerts |

| Physiological Needs of the Elderly | Easy operation, Health monitoring, Task reminders | |

| Psychological Needs of the Elderly | Companionship & empathy, Entertainment, Interest cultivation, Information access |

Weight Analysis of the User Need Hierarchy

To translate qualitative needs into actionable design priorities, I applied a weight analysis to the hierarchical model. This involves constructing fuzzy pairwise comparison matrices, assigning values based on established scales, calculating weight vectors, and determining an overall priority order.

Constructing Fuzzy Complementary Judgment Matrices

For elements \(a_1, a_2, a_3, …, a_n\) under a common parent criterion, a judgment matrix \(E_n = (e_{ij})_{n \times n}\) is established, where \(e_{ij}\) represents the relative importance of element \(a_i\) over \(a_j\). Using Saaty’s standard scale, values are assigned as shown in Table 1.

| Relative Importance | Assigned Value (\(e_{ij}\)) |

|---|---|

| Equally Important | 1 |

| Moderately More Important | 3 |

| Essentially More Important | 5 |

| Very Strongly More Important | 7 |

| Absolutely More Important | 9 |

| Intermediate Values | 2, 4, 6, 8 |

The matrix is complementary, satisfying \(e_{ji} = 1 / e_{ij}\). Based on the research data, pairwise comparison matrices were constructed for the three second-tier clusters relative to the overall goal (Matrix A), and for needs within each cluster (Matrices B1, B2, B3).

$$E_A = \begin{bmatrix}

1 & 1/2 & 1/3 \\

2 & 1 & 1/2 \\

3 & 2 & 1

\end{bmatrix}$$

where \(a_1\): Children’s Needs, \(a_2\): Physiological Needs, \(a_3\): Psychological Needs.

Calculating Fuzzy Weight Vectors

The weight calculation for a fuzzy complementary matrix \(E\) involves several steps. First, sum each row:

$$r_i = \sum_{k=1}^{n} e_{ik}, \quad \text{for } i=1,2,…,n$$

Then, apply a mathematical transformation to convert \(E\) into a fuzzy consistent matrix \(R\):

$$r_{ij} = \frac{r_i – r_j}{2(n-1)} + 0.5$$

Finally, normalize the rows of matrix \(R\) to obtain the weight vector \(W = (w_1, w_2, …, w_n)^T\):

$$w_i = \frac{\sum_{j=1}^{n} r_{ij}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{j=1}^{n} r_{ij}}, \quad \text{satisfying } \sum_{i=1}^{n} w_i = 1$$

Applying this process to the matrices yields the local weight vectors. For Matrix \(E_A\), the calculated weight vector for the second-tier clusters is approximately:

$$W_A = (0.16, 0.30, 0.54)^T$$

This indicates that within the overall goal, the psychological needs of the elderly (\(a_3\)) are deemed most critical, followed by their physiological needs (\(a_2\)), and then the children’s needs (\(a_1\)).

Overall Priority Ranking

The global weight of a specific need is the product of its local weight within its cluster and the weight of its parent cluster. The formula is:

$$\text{Global Weight}(s_{ij}) = W(\text{Cluster}_i) \times W(s_{ij} | \text{Cluster}_i)$$

where \(s_{ij}\) is the j-th specific need under the i-th cluster. Calculating this for all terminal needs in the hierarchy produces the final priority ranking, as shown in Table 2.

| Rank | Specific Need | Global Weight | Originating Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Easy Operation / Simplified Control | 0.165 | Physiological |

| 2 | Health Monitoring | 0.150 | Physiological |

| 3 | Companionship & Empathetic Interaction | 0.135 | Psychological |

| 4 | Real-time Safety Monitoring & Alerts | 0.128 | Children’s Needs |

| 5 | Task & Medication Reminders | 0.105 | Physiological |

| 6 | Entertainment & Mental Engagement | 0.095 | Psychological |

| 7 | Access to News/Weather Information | 0.090 | Psychological |

| 8 | Remote Communication with Family | 0.064 | Children’s Needs |

| 9 | Interest Cultivation | 0.048 | Psychological |

| 10 | Emergency Alert to Family | 0.020 | Children’s Needs |

This prioritized list provides a clear, data-driven mandate for the design phase. The top four needs—easy operation, health monitoring, companionship, and real-time safety monitoring—form the primary design pillars for the companion robot.

Defining the Companion Robot Design Concept

Guided by the weighted user needs, the product design concept is defined as follows: To design a companion robot for solo-living seniors aged 55+, focusing on extremely simple operation, providing empathetic companionship and conversation, monitoring health and safety, and facilitating family connection. The key functional pillars derived from this concept are:

1. Intelligent and Simplified Control: To mitigate the digital divide, the companion robot will employ a multi-modal control scheme combining voice commands (with natural language processing), and a minimalist physical interface with large, tactile buttons. Advanced features like face recognition can be used for personalized greetings. The core principle is to make every interaction intuitive, requiring minimal learning.

2. Integrated Health Monitoring: The robot will serve as a hub for health data, compatible with wearable devices (e.g., smart bracelets) to track vital signs like heart rate and daily activity. It will analyze trends, provide gentle health suggestions, and maintain a simple digital health log for chronic conditions, offering timely reminders for medication or exercises.

3. Proactive Companionship and Emotional Support: Moving beyond pre-programmed responses, the companion robot will use AI-driven dialogue systems to engage in meaningful, context-aware conversations, reminisce about past stories input by the family, and even detect vocal tones to gauge mood. Coupled with soft, responsive lighting that changes color based on interaction or time of day, it aims to create an emotionally supportive presence.

4. Essential Information Gateway: A single dedicated button will trigger a clear, audible broadcast of the latest news headlines and weather forecast. This function addresses the need for easy access to crucial information, ensuring seniors are informed and can take necessary precautions without navigating complex apps or websites.

5. Proactive Safety and Reminder System: The robot will manage daily task reminders (e.g., “The kettle is on,” “It’s time for your walk”). Crucially, it will incorporate fall detection technology (via connected wearables or onboard sensors) and hazard monitoring (e.g., smoke/gas alarm linkage). In an emergency, it can automatically place calls to pre-set emergency contacts and a monitoring center.

6. Seamless Family Interaction Bridge: A dedicated mobile application for family members will allow them to send voice messages, photos, or calendar notes directly to the companion robot, which presents them simply to the elder. Conversely, the elder can easily record voice messages or reminders for the family through the robot, facilitating a smooth, low-friction communication loop.

Design Practice for the User-Centered Companion Robot

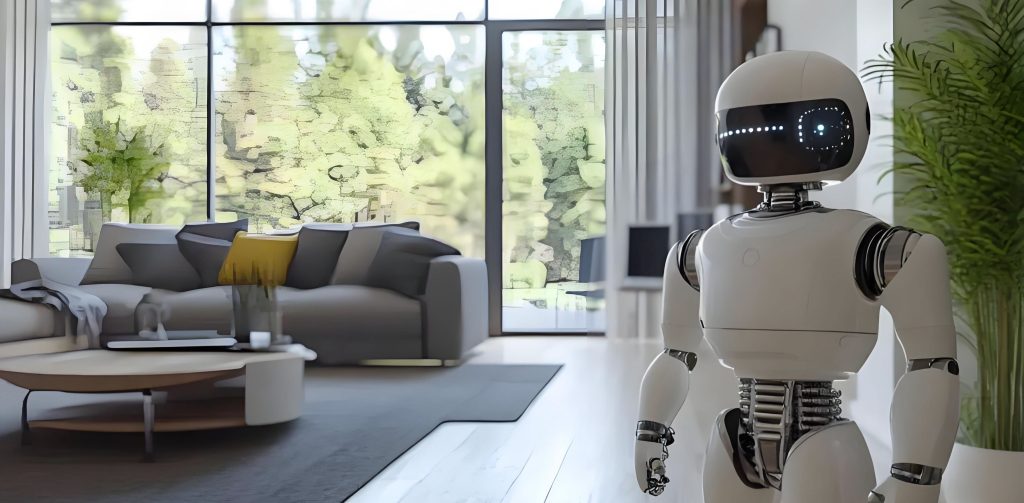

Translating the defined concept into a tangible product involves applying specific design principles across multiple dimensions. The primary use scenario is as a stationary unit on a table or shelf within the living space.

Functional Architecture & Interaction Design

The functional design directly addresses the priority needs. Smart voice control is the primary interaction mode, supplemented by a few large, backlit physical buttons for core functions (News, Call Family, Emergency). To manage cost and complexity, the robot itself does not include a large video screen but is designed to wirelessly connect to a family member’s existing tablet or smart TV for video calls or photo viewing. Health monitoring is implemented as an expandable module via Bluetooth pairing with standard wearables. The reminder and alarm functions are integrated into the core dialogue and alert system.

Form and CMF Design

The form language is deliberately non-humanoid but warmly anthropomorphic. Research suggests that overly realistic humanoid robots can trigger unease (the “uncanny valley” effect). Instead, the form is inspired by the soft, rounded proportions of a young animal or a plush toy, employing gentle, continuous curves. This approach evokes feelings of innocence and approachability, making the companion robot seem friendly and non-threatening. The size is compact, designed for domestic spaces without being imposing.

For Color, Material, and Finish (CMF), the palette avoids sterile whites or cold greys. The main body uses warm, matte-finish materials like soft-touch plastics or fabric-wrapped surfaces in off-white or light grey tones. Accents in muted blues, greens, or oranges add visual interest without being overwhelming. The use of matte finishes, slightly textured surfaces, and warm fabric accents makes the device feel more tactile and “alive,” reducing the coldness associated with technology and enhancing the perceived warmth of the companion robot.

Ergonomics and Interaction Design

The companion robot is a tool for augmentation, not replacement. Its interaction design is tailored to common age-related impairments. Voice output is clear and at an adjustable, louder-than-standard volume. Any textual feedback on connected devices uses very large, high-contrast fonts. The physical interface employs a “familiarity principle”: the layout and style of buttons are reminiscent of classic, reliable devices from the user’s past (e.g., old radios or telephones), reducing cognitive load and fostering immediate comfort. The device’s height and control placement are determined based on average elderly sitting posture and reach envelopes.

Emotional and Experience Design

Emotional design is woven into both form and interaction. The cute, non-threatening form subconsciously triggers nurturing feelings. More importantly, experiential familiarity is engineered into the interaction. The sound of a button press, the quality of the voice (calm, respectful, slightly slower-paced), and the logic of menu structures (simple, linear) are all crafted to feel dependable and reassuring. The companion robot can initiate positive interactions, like playing a favorite piece of music from the user’s youth in the morning or asking about a cherished memory, thereby building a bond and fostering reflective pleasure—the highest level of Norman’s UX hierarchy.

Conclusion

The design of an elderly companion robot presents the unique challenge of serving two distinct user groups: the primary elderly user and their concerned family. A successful design must seamlessly integrate the needs of both. This paper has demonstrated a structured, user-experience-driven methodology to address this challenge. By systematically gathering user insights, constructing a hierarchical need model, and applying a fuzzy weight analysis, the often-implicit needs are not only made explicit but also quantitatively prioritized. This analysis unequivocally highlights ease of use, health monitoring, empathetic companionship, and safety as the foundational pillars for design.

The subsequent translation of these priorities into a concrete product concept and design practice shows how theory informs practice. The proposed companion robot moves beyond a mere functional appliance to become an accessible, warm, and intelligent presence in the home. It emphasizes intuitive interaction over technological complexity, and emotional support over mere surveillance. The focus on familiar interaction patterns and emotionally resonant design elements is crucial for user acceptance and long-term engagement. This human-centered approach, grounded in rigorous UX analysis, provides a valuable framework and actionable insights for developing future companion robots that truly enhance the lives of the elderly, offering them security, connection, and a renewed sense of agency in their daily lives.