In the realm of precision motion control, particularly within the robotics industry, the demand for high-performance power transmission components has surged. The harmonic drive gear, known for its compact size, high reduction ratio, and zero-backlash capability, stands as a critical component. However, achieving the trifecta of high torque capacity, long operational life, and exceptional positional accuracy remains a significant engineering challenge. This article delves into the advanced design, simulation, and verification of a double-circular-arc tooth profile for harmonic drive gears, presenting a comprehensive, first-person perspective on the methodologies and tools developed to overcome these challenges.

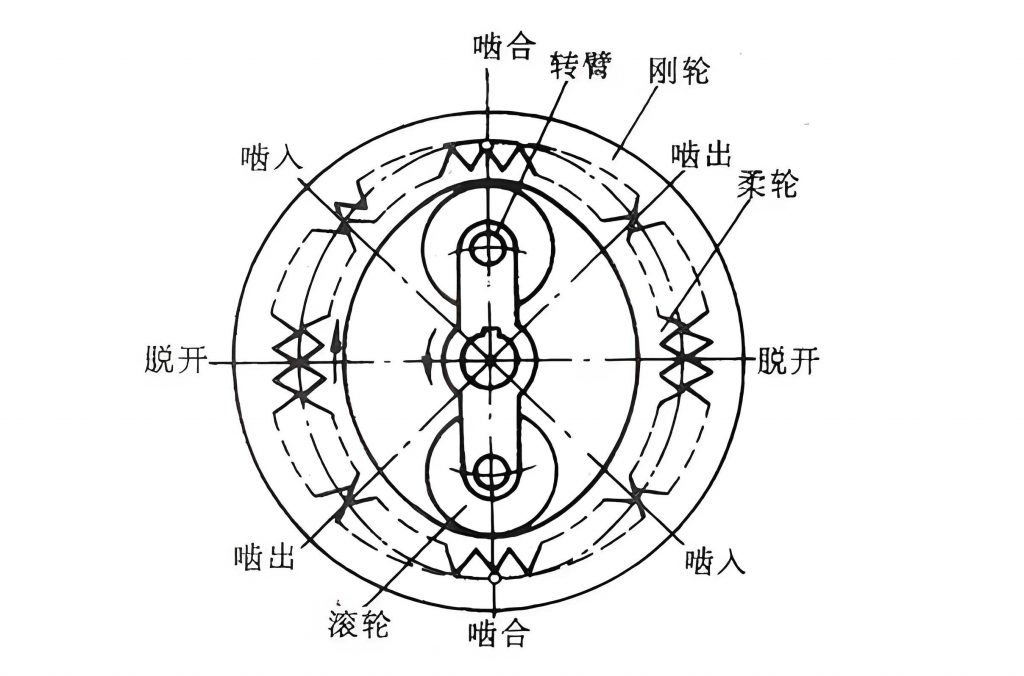

The fundamental components of a harmonic drive gear are the wave generator (input), the flexible spline or flexspline (output), and the circular spline or rigid gear (fixed). The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam paired with a thin-walled bearing, deforms the flexspline into a non-circular shape. This deformation forces the teeth of the flexspline to engage with those of the rigid gear at two diametrically opposite regions. As the wave generator rotates, the points of engagement travel, causing a relative rotation between the flexspline and the rigid gear. The high reduction ratio is derived from the difference in the number of teeth between the two splines, typically by two. The design of the tooth profile that facilitates this unique meshing action is paramount to the device’s performance.

Traditional involute profiles, while simple to manufacture, suffer from a limited number of simultaneously engaged tooth pairs under load. This leads to higher stress concentrations, reduced torque capacity, and accelerated wear. In contrast, the double-circular-arc profile is engineered to provide conjugate or near-conjugate meshing over a larger arc of engagement. This design promotes load sharing across multiple teeth, thereby enhancing the overall torque density, stiffness, and longevity of the harmonic drive gear. Despite its proven advantages, the precise parametric design of this profile, accounting for the complex elastic deformation of the flexspline, has been a considerable barrier.

Core Principles and Parametric Modeling of the Double-Circular-Arc Profile

The development of an accurate design methodology begins with establishing a robust theoretical model. To make the complex problem tractable, several key assumptions are made: the flexspline is treated as a thin-walled ring; its neutral curve undergoes no elongation; tooth profiles are considered rigid relative to the flexspline wall; the transmission ratio is constant and kinematic effects from load-induced deformations are neglected; and the wave generator is a perfect, rigid elliptical contour.

The undeformed flexspline tooth profile is constructed from five distinct segments: a tip arc, an upper (active) flank arc, a connecting straight line (tangent), a lower (root) flank arc, and a root fillet arc. The double-circular-arc nomenclature specifically refers to the two primary flank arcs. The geometry is defined by a set of interrelated parameters, whose symbols and meanings are summarized below.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| $m$ | Module |

| $Z_f$, $Z_r$ | Number of teeth on flexspline and rigid gear |

| $x_f^*$ | Addendum modification coefficient for flexspline |

| $\rho_a$, $\rho_f$ | Radii of the upper and lower flank arcs |

| $\rho_c$ | Radius of the root fillet arc |

| $r_f$, $r_m$ | Pitch circle and neutral curve radii of the undeformed flexspline |

| $R_{af}$, $R_{ff}$ | Addendum and dedendum circle radii of the flexspline |

| $e_a$, $e_f$ | Distance from the pitch circle to the centers of the upper/lower flank arcs |

| $\theta_1$, $\theta_2$ | Start and end angles of the upper flank arc |

| $\theta_3$, $\theta_4$ | Start and end angles of the lower flank arc |

| $(x_a, y_a)$, $(x_f, y_f)$ | Coordinates of the upper and lower flank arc centers |

The coordinates of a point on the tooth profile in a coordinate system fixed to the tooth’s symmetry axis ($X_2O_2Y_2$) are denoted as $x(\theta_x)$ and $y(\theta_x)$, where $\theta_x$ is a curve parameter. The equations for each segment, such as the upper flank arc, are given by:

$$ x_{c1} = x_a + \rho_a \cos(\theta_x), \quad y_{c1} = y_a + \rho_a \sin(\theta_x), \quad \theta_1 \le \theta_x \le \theta_2 $$

These segments are connected via geometric continuity ($C^1$) conditions, leading to a system of constraint equations that define all parameters from a primary set of design choices (e.g., $m$, $Z_f$, $Z_r$, $\rho_a$, $\rho_f$, $e_a$, $e_f$).

The heart of the harmonic drive gear analysis lies in modeling the flexspline’s deformation. When the wave generator is inserted, a point $P$ on the neutral curve at an angular position $\theta$ from the major axis undergoes radial displacement $u(\theta)$ and tangential displacement $v(\theta)$. For a simple elliptical wave generator, these can be approximated as:

$$ u(\theta) = w_0 \cos(2\theta), \quad v(\theta) = -\frac{w_0}{2} \sin(2\theta) $$

where $w_0$ is the radial deformation amplitude at the major axis. Additionally, the cross-section rotates by an angle $\gamma(\theta)$, which for a non-elongating neutral curve is $\gamma(\theta) = -v(\theta)/r_m$.

The transformation of a tooth profile point from its undeformed position to its deformed state in the fixed coordinate system ($X_1O_1Y_1$) involves a sequence of operations: the initial positioning of the undeformed tooth, followed by the application of the neutral curve displacements and the cross-sectional rotation. Let $X_{t1}, Y_{t1}$ be the coordinates of a profile point from the undeformed tooth positioned at angle $\theta$:

$$ \begin{aligned}

X_{t1} &= r_m \sin\theta + x(\theta_x)\cos\theta + (y(\theta_x)-r_m)\sin\theta \\

Y_{t1} &= r_m \cos\theta – x(\theta_x)\sin\theta + (y(\theta_x)-r_m)\cos\theta

\end{aligned} $$

The new position of the neutral curve point $O_2$ is:

$$ \begin{aligned}

X_{t2} &= (r_m + u(\theta))\sin\theta + v(\theta)\cos\theta \\

Y_{t2} &= (r_m + u(\theta))\cos\theta – v(\theta)\sin\theta

\end{aligned} $$

Finally, the deformed tooth profile coordinates $(X_2, Y_2)$ are obtained by rotating the vector from $O_2$ to the profile point by $\gamma(\theta)$:

$$ \begin{aligned}

X_2 &= X_{t2} + (X_{t1} – r_m\sin\theta)\cos\gamma + (Y_{t1} – r_m\cos\theta)\sin\gamma \\

Y_2 &= Y_{t2} – (X_{t1} – r_m\sin\theta)\sin\gamma + (Y_{t1} – r_m\cos\theta)\cos\gamma

\end{aligned} $$

This set of equations, $X_2(\theta_x, \theta)$ and $Y_2(\theta_x, \theta)$, describes the family of flexspline tooth profiles as a function of the wave generator’s angular orientation, implicitly defined by $\theta$.

The conjugate tooth profile for the rigid gear is found by applying the theory of gearing. As the wave generator rotates by an angle $\phi_1$, the flexspline rotates by $\phi_2 = -\phi_1 / i$, where $i = Z_f / (Z_f – Z_r)$ is the reduction ratio (typically a large negative number). The family of flexspline profiles in the fixed frame becomes $X_2^T(\theta_x, \phi_1), Y_2^T(\theta_x, \phi_1)$ after applying this rotation. The envelope of this family, which is the rigid gear tooth profile $(X_1, Y_1)$, satisfies the meshing equation:

$$ \frac{\partial X_2^T}{\partial \theta_x} \frac{\partial Y_2^T}{\partial \phi_1} – \frac{\partial X_2^T}{\partial \phi_1} \frac{\partial Y_2^T}{\partial \theta_x} = 0 $$

Solving this system numerically for $\theta_x$ and $\phi_1$ yields the coordinates of the rigid gear tooth profile. The profiles for the generating tools (hob for the flexspline, shaper cutter for the rigid gear) are subsequently derived through a secondary envelope process based on the same principles.

Development of a Parametric Computer-Aided Design (CAD) Software

Translating the theoretical model into a practical design tool was essential. A dedicated CAD software was developed to automate the entire process. The software architecture is modular, allowing for efficient computation and visualization.

| Module | Function | Key Output |

|---|---|---|

| Input & Pre-processing | Accepts design specifications (ratio, torque, size), material properties, and primary tooth parameters. | Validated set of geometric and kinematic parameters. |

| Geometric Model Solver | Solves the constraint equations for the undeformed double-circular-arc flexspline profile. | Complete set of coordinates for the 5-segment tooth profile. |

| Kinematic & Deformation Solver | Computes the deformed flexspline profile family using the displacement and rotation fields. | Mathematical representation $X_2(\theta_x, \phi_1), Y_2(\theta_x, \phi_1)$. |

| Conjugate Profile Generator | Numerically solves the envelope equation to generate the rigid gear tooth profile. | Point cloud data for the rigid gear conjugate profile. |

| Tooling Profile Calculator | Performs secondary envelope calculations to derive hob and shaper cutter profiles. | Point cloud and best-fit circular arc parameters for cutting tools. |

| Post-processing & Validation | Calculates measurement over pins/balls (M-values), performs clearance checks, and visualizes meshing. | Quality assurance data and graphical plots of meshing sequences. |

The software outputs not only point cloud data for manufacturing but also provides best-fit circular arc parameters for the generated rigid gear and tool profiles. This is crucial because while the theoretically generated profiles are not perfect arcs, they are extremely close. Fitting them to arcs with sub-micron accuracy facilitates metrology and standard manufacturing processes. A typical output for a shaper cutter profile, visualized within the software, confirms its near-circular-arc nature.

Enhancing Accuracy: Accounting for Complex Flexspline Deformation via FEA

The initial model assumes a simple, thin-cylindrical flexspline. In reality, a harmonic drive gear flexspline has a complex structure with a diaphragm or bell-shaped end for mounting and torque output. This end structure imposes additional boundary conditions that significantly alter the deformation field $u(\theta), v(\theta), \gamma(\theta)$ from the simple elliptical assumption, leading to meshing interference, increased stress, noise, and reduced life if unaccounted for.

To achieve true precision, a hybrid analytical-FEA approach is adopted. A detailed 3D finite element model of the assembly (wave generator, flexspline, rigid gear) is created. Contact conditions are defined between the wave generator bearing and the flexspline bore, and between the flexspline and rigid gear teeth. After solving the nonlinear contact problem, the nodal displacements along the flexspline’s neutral layer are extracted.

| Model Type | Deformation Field Source | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Analytical | Elliptical assumption: $u=w_0\cos2\theta$ | Fast computation, good for initial design. | Ignores end effects, leads to interference in real gears. |

| FEA-Corrected | Nodal displacements from 3D FEA of full assembly. | Captures true deformation, enables precise conjugate design. | Computationally intensive, requires accurate FEA modeling. |

The extracted discrete displacement data $(x_k, y_k)$ for the deformed neutral curve is then fitted with a smooth cubic spline $S(x)$ to create a continuous and differentiable representation for use in the conjugate profile equations. For $n$ intervals between points $x_k$ and $x_{k+1}$ ($k=1,…,n$), with $h_k = x_{k+1} – x_k$, the cubic spline on the $k$-th interval is:

$$ S_k(x) = \frac{M_k (x_{k+1}-x)^3}{6h_k} + \frac{M_{k+1} (x-x_k)^3}{6h_k} + \left( y_k – \frac{M_k h_k^2}{6} \right) \frac{x_{k+1}-x}{h_k} + \left( y_{k+1} – \frac{M_{k+1} h_k^2}{6} \right) \frac{x-x_k}{h_k} $$

The second derivative moments $M_k$ are found by solving a tridiagonal system derived from $C^2$ continuity and end conditions:

$$

\begin{bmatrix}

2 & \lambda_1 & & & \\

\mu_2 & 2 & \lambda_2 & & \\

& \ddots & \ddots & \ddots & \\

& & \mu_{n} & 2 & \lambda_{n} \\

& & & \mu_{n+1} & 2

\end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix}

M_1 \\

M_2 \\

\vdots \\

M_n \\

M_{n+1}

\end{bmatrix}

=

\begin{bmatrix}

d_1 \\

d_2 \\

\vdots \\

d_n \\

d_{n+1}

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where $\mu_k = h_{k-1}/(h_{k-1}+h_k)$, $\lambda_k = 1-\mu_k$, and $d_k$ are constants based on the data points and end slopes.

This spline function $S(x)$ accurately represents the FEA-derived neutral curve. Its first derivative gives the slope, from which the local radial displacement $u$ and tangential displacement $v$ can be deduced relative to the original circle. This refined deformation model is then fed back into the kinematic equations for the deformed tooth profile and the subsequent conjugate rigid gear profile calculation. The result is a set of tooth profiles that, in theory, should mesh perfectly with the *actual* deformed shape of the complex flexspline.

Verification and Conclusion

The final verification step involves closing the loop. The newly generated “FEA-corrected” rigid gear profile is imported back into a new finite element model. A full assembly simulation is run. The results demonstrate a dramatic improvement: the severe interference observed when using profiles based on the simple elliptical model is eliminated. The flexspline teeth, undergoing their true complex deformation, now mesh smoothly with the rigid gear teeth along the intended zones of contact, with minimal penetration and uniform clearance elsewhere.

This successful verification confirms the validity of the entire parametric design and simulation workflow. The development of a dedicated CAD software based on a rigorous theoretical model for the harmonic drive gear has proven to be a transformative step. It drastically reduces the reliance on costly and time-consuming trial-and-error prototyping. The integration of high-fidelity FEA to capture real-world deformation characteristics of complex flexspline geometries allows for the design of truly conjugate double-circular-arc profiles. This methodology directly addresses the core performance limitations of traditional designs, paving the way for harmonic drive gears with significantly enhanced torque capacity, positional accuracy, operational life, and reliability—key enablers for the next generation of robotic and precision industrial systems.

Future work will focus on further refining the model by incorporating the effects of neutral curve elongation under load, studying the impact of instantaneous transmission ratio variations on ultra-high precision requirements, and optimizing the flexspline end geometry to inherently produce a more favorable deformation field that minimizes meshing disturbances even before corrective design steps are taken.