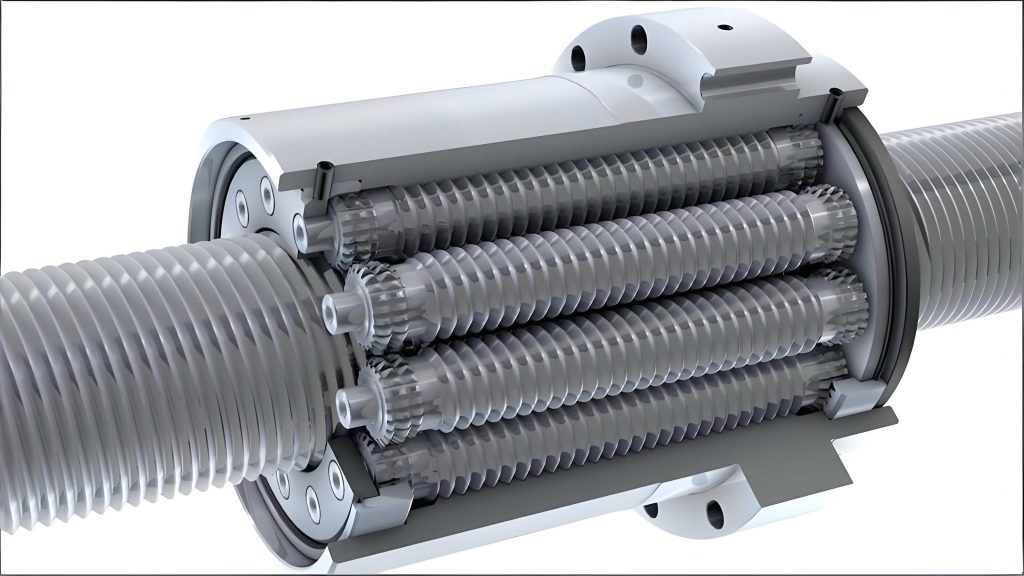

In my analysis of high-performance motion conversion systems, the planetary roller screw stands out for its exceptional load capacity, rigidity, and efficiency. Its operating principle, converting rotary motion into linear translation via multiple threaded rollers acting as planets between a central screw and a peripheral nut, offers significant advantages over traditional ball screws. However, the precision of this meshing action is paramount. Deviations from ideal thread geometry, inherent to manufacturing processes, directly alter the contact conditions between the screw, rollers, and nut. This can lead to either detrimental backlash, compromising positioning accuracy, or excessive interference, causing elevated friction, premature wear, and reduced efficiency and lifespan. Therefore, in my work, I focus on establishing a precise spatial meshing model to quantify these effects and analyze how specific thread profile errors influence the meshing state of the planetary roller screw.

The analysis begins with defining the geometry. For a standard planetary roller screw configuration, I consider threads with a triangular profile. Typically, the screw and nut have straight flanks in the axial section, while the roller thread profile is often ground with a circular arc to promote favorable point contact conditions, reducing stress concentrations. The key geometric parameters I will refer to throughout this analysis are the pitch $P_0$, the thread flank half-angle $\beta$, the nominal pitch diameters for the screw ($d_s$), rollers ($d_r$), and nut ($d_n$), and the radius of the circular arc on the roller thread, $R_r$. The relationship between pitch and lead is defined by the number of thread starts $N$: $P = N \cdot P_0$.

To mathematically capture the meshing interaction, I establish a set of coordinate systems based on spatial gearing theory. A fixed global coordinate system $O(x, y, z)$ is defined with the screw/nut axis along $z$. A roller coordinate system $O_R(x_R, y_R, z_R)$ is attached to a representative roller, with its $z_R$ axis aligned with the roller’s own axis. The origin $O_R$ is offset from $O$ by the center distance $a$. Additionally, I define cross-sectional coordinate systems for the roller $O_r(x_r, y_r, z_r)$, screw $O_s(x_s, y_s, z_s)$, and nut $O_n(x_n, y_n, z_n)$ to conveniently describe their thread profiles before applying the helical motion.

The heart of my model lies in deriving the parametric equations for the helical surfaces of each component. Starting with the roller, a point $M$ on its left-side profile (circular arc) in its cross-section system is given by:

$$ \vec{r}_{rM}(u_r) = \begin{bmatrix} R_r \sin u_r – R_r \sin \beta + r_r \\ 0 \\ -P_0/4 + R_r \cos \beta – R_r \cos u_r \end{bmatrix} $$

where $u_r$ is an angular parameter defining the point on the arc, and $r_r = d_r/2$ is the roller’s pitch radius. Transforming this profile into the fixed system and applying its helical motion (rotation $\theta_r$ about its axis and translation $P_r \theta_r / (2\pi)$ along $z_R$, where $P_r$ is the roller lead), yields the roller’s left helical surface:

$$ \vec{r}_r(u_r, \theta_r) = \begin{bmatrix} (R_r \sin u_r – R_r \sin \beta + r_r) \cos \theta_r \\ (R_r \sin u_r – R_r \sin \beta + r_r) \sin \theta_r + a \\ -P_0/4 + R_r \cos \beta – R_r \cos u_r + \frac{P_r}{2\pi}\theta_r \end{bmatrix} $$

For the screw’s right-side flank (straight line), a point in its cross-section is $\vec{r}_{sM}(u_s) = [u_s \cos \beta + r_s, 0, P_0/4 + u_s \sin \beta]^T$, where $u_s$ is a linear parameter and $r_s$ is the screw’s pitch radius (treated as a variable for zero-backlash calculation). Applying the screw’s helical motion (rotation $\theta_s$, translation $P_s \theta_s/(2\pi)$) gives:

$$ \vec{s}_s(u_s, \theta_s, r_s) = \begin{bmatrix} (u_s \cos \beta + r_s) \cos \theta_s \\ (u_s \cos \beta + r_s) \sin \theta_s \\ P_0/4 + u_s \sin \beta + \frac{P_s}{2\pi}\theta_s \end{bmatrix} $$

Similarly, the nut’s right-side helical surface is:

$$ \vec{r}_n(u_n, \theta_n, r_n) = \begin{bmatrix} (u_n \cos \beta + r_n) \cos \theta_n \\ (u_n \cos \beta + r_n) \sin \theta_n \\ -P_0/4 + u_n \sin \beta + \frac{P_n}{2\pi}\theta_n \end{bmatrix} $$

where $r_n$ is the nut’s pitch radius. The condition for continuous meshing between two surfaces, according to space gearing theory, is that their relative velocity at the contact point is orthogonal to the common normal vector. For the roller-screw pair, this is expressed as $\vec{v}_{rs} \cdot \vec{n} = 0$. A more direct condition for the contact of two helical surfaces with a common normal is the colinearity of their surface normal vectors at the contact point. The normal vector $\vec{n}$ to a surface $\vec{r}(u, \theta)$ is found from the cross product of the partial derivatives: $\vec{n} = \frac{\partial \vec{r}}{\partial u} \times \frac{\partial \vec{r}}{\partial \theta}$.

Therefore, the meshing condition for the roller and screw reduces to a system of equations stating that a contact point exists where their position vectors and the directions of their normal vectors coincide:

$$

\begin{cases}

\vec{r}_r(u_r, \theta_r) = \vec{r}_s(u_s, \theta_s, r_s) \\

\frac{n_{rx}}{n_{sx}} = \frac{n_{ry}}{n_{sy}} = \frac{n_{rz}}{n_{sz}}

\end{cases}

$$

This is a system of six nonlinear equations (three from coordinate equality, two independent from normal colinearity) with six unknowns: $u_r, \theta_r, u_s, \theta_s, r_s$, and the axial coordinate of the contact point. Solving this system yields the precise contact point coordinates and, critically, the required screw pitch radius $r_s$ for zero clearance at that specific meshing position. An identical set of equations is established for the roller-nut pair to solve for $r_n$.

Solving these nonlinear equations requires a numerical approach. In my analysis, I employ the Newton-Raphson iterative method. To demonstrate, I use a specific example of a standard planetary roller screw with theoretical parameters derived from kinematic relations (ensuring proper motion transfer).

| Geometric Parameter | Screw | Roller | Nut |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Diameter (mm) | 19.5 | 6.5 | 32.5 |

| Pitch, $P_0$ (mm) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Number of Starts | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Lead, $P$ (mm) | 2.0 | 0.4 | 2.0 |

| Flank Half-Angle, $\beta$ (deg) | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Roller Profile Arc Radius, $R_r$ (mm) | – | 3.0 | – |

| Center Distance, $a$ (mm) | 13.0 | ||

Applying the numerical solution to the meshing equations for the system defined in Table 1 provides the actual pitch radii required for zero clearance, contrasting with the kinematically derived theoretical values.

| Component Pair | Theoretical Pitch Radius (mm) | Calculated Zero-Backlash Radius (mm) | Implied State with Theoretical Radius |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roller-Screw | 9.7500 | 9.746675 | Significant Interference |

| Roller-Nut | 16.2500 | $\approx$16.2500 | Near-Zero Interference |

This key result from my model reveals a crucial insight: designing a planetary roller screw based purely on kinematic equations can lead to substantial interference between the rollers and the screw. The actual screw pitch diameter for proper meshing is slightly smaller than the theoretical value. This interference, if not accounted for in manufacturing, would cause high initial friction and wear.

Building on this zero-backlash baseline, I now investigate the sensitivity of the meshing state to specific manufacturing errors. The “meshing state” is quantified as the axial clearance (positive value) or interference (negative value) at the calculated contact point when an error is introduced into one parameter while holding others at their nominal zero-backlash values.

1. Pitch Diameter Error: I vary the pitch radius of each component ($r_s$, $r_r$, $r_n$) by ±0.05 mm (diameter error ±0.1 mm). The effect on axial clearance is pronounced and linear, as the governing equations are highly sensitive to radial dimensions. The relationship can be summarized as:

$$ \delta_{axial} \approx -k_s \cdot \Delta r_s – k_r \cdot \Delta r_r + k_n \cdot \Delta r_n $$

where $\delta_{axial}$ is the axial clearance change, $\Delta r$ are the radius errors, and $k$ are positive sensitivity coefficients. An increase in screw or roller radius reduces clearance (increases interference), while an increase in nut radius increases clearance. This error has the most direct and largest magnitude impact on the meshing state of the planetary roller screw.

2. Pitch Error: I introduce errors in the fundamental pitch $P_0$ for each component within ±0.05 mm. The effect is also linear but with a slightly lower sensitivity coefficient than pitch diameter errors. The trends are distinct:

$$ \delta_{axial} \approx -c_s \cdot \Delta P_{0,s} + c_r \cdot \Delta P_{0,r} – c’_r \cdot \Delta P_{0,r} + c_n \cdot \Delta P_{0,n} $$

For the roller-screw pair, screw pitch increase reduces clearance; roller pitch increase increases clearance. For the roller-nut pair, roller pitch increase reduces clearance; nut pitch increase increases clearance. Pitch error is the second most critical factor to control in the manufacturing of a planetary roller screw.

3. Flank Half-Angle Error ($\Delta \beta$): I analyze errors within ±0.5° for each component’s half-angle. The response is nonlinear, approximately parabolic. For the roller and nut, any deviation from the nominal angle causes interference, with the minimum interference occurring at zero error. For the screw, the relationship is more complex: negative errors (smaller angle) cause interference, while small positive errors first create a small clearance before also leading to interference at larger positive errors. The magnitude of clearance change is on the order of $10^{-4}$ mm, significantly smaller than for pitch diameter or pitch errors.

4. Roller Thread Profile Arc Radius Error ($\Delta R_r$): Varying $R_r$ by ±0.5 mm shows a minimal, approximately linear effect on the roller-screw clearance and virtually no effect on the roller-nut clearance. The change is on the order of $10^{-9}$ mm, which is negligible from an engineering standpoint. This parameter is primarily optimized for contact stress, not for clearance control.

The results of my sensitivity analysis are consolidated below, ranking the influence of various errors on the meshing state of the planetary roller screw.

| Error Type | Typical Error Range | Effect on Axial Clearance | Magnitude Order | Engineering Criticality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Diameter | ±0.1 mm (dia.) | Linear, High Sensitivity | $10^{-1}$ to $10^{0}$ mm | Highest – Must be tightly controlled |

| Pitch ($P_0$) | ±0.05 mm | Linear, Medium Sensitivity | $10^{-2}$ to $10^{-1}$ mm | High – Requires precision machining |

| Flank Half-Angle | ±0.5° | Nonlinear (Parabolic), Low Sensitivity | $10^{-4}$ mm | Low – Standard process capability is sufficient |

| Roller Arc Radius | ±0.5 mm | Quasi-Linear, Very Low Sensitivity | $10^{-9}$ mm | Negligible for clearance |

Through this detailed modeling and analysis, I conclude that the meshing state of a planetary roller screw is exquisitely sensitive to certain geometric tolerances. My model successfully quantifies the zero-backlash condition, revealing that the kinematically derived screw diameter often needs a slight corrective reduction. Furthermore, the analysis clearly identifies pitch diameter and pitch as the most critical parameters to monitor and control during the manufacture of the planetary roller screw components, as errors in these directly and significantly translate into operational backlash or damaging interference. Errors in flank angle and roller profile radius have a comparatively minor effect on clearance. These findings align with practical manufacturing challenges and provide a quantitative foundation for setting meaningful tolerances to ensure the reliable and efficient performance of the planetary roller screw mechanism.