In modern mechanical transmission systems, the planetary roller screw mechanism stands out as a highly efficient device for converting rotary motion into linear motion. Similar to ball screw mechanisms, the planetary roller screw mechanism offers advantages such as high load capacity, precision, longevity, and shock resistance. These properties have led to its widespread adoption in aerospace, automotive, and precision machining industries. However, the performance of a planetary roller screw mechanism is intrinsically linked to the contact characteristics between its threads, specifically between the screw, rollers, and nut. Understanding these contact interactions requires precise knowledge of the principal curvatures at the contact points, which directly influence the contact area, stress distribution, friction, and overall durability. This article presents a comprehensive analysis of the principal curvature calculation and contact characteristics for a planetary roller screw mechanism, employing a generalized approach based on differential geometry and Hertzian contact theory.

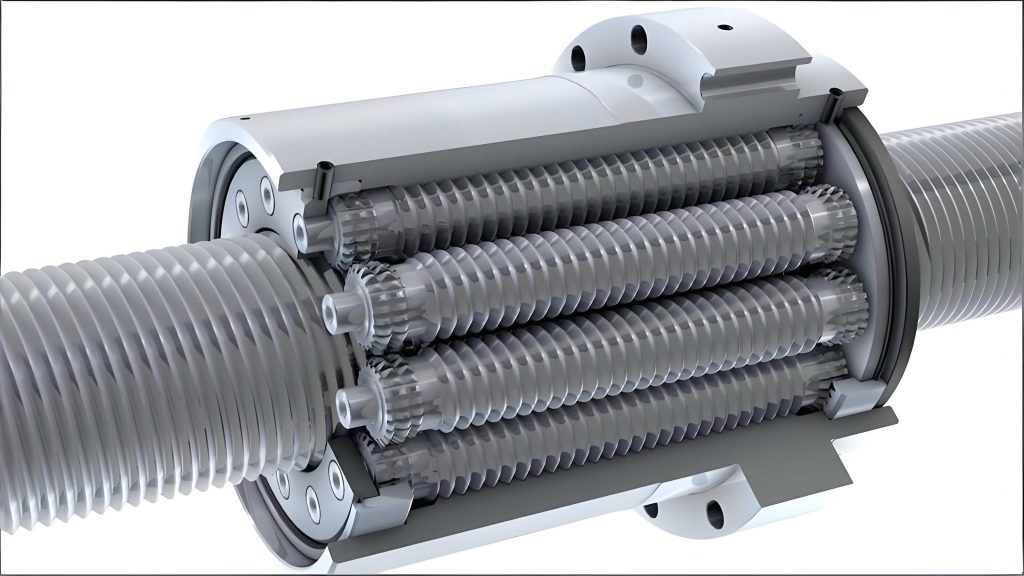

The planetary roller screw mechanism consists of a screw with multiple-start external threads, a nut with multiple-start internal threads, and several rollers with single-start external threads arranged circumferentially around the screw. The rollers are held in place by a retainer and engage with internal gear rings at the nut ends to ensure proper motion. When the screw rotates, the rollers both revolve around the screw axis and rotate about their own axes, transmitting motion and force through contact interfaces between the screw-roller and nut-roller. These interfaces involve spatial helical surfaces, making the contact analysis complex. Traditional methods often approximate the roller threads as spherical balls, similar to ball screw mechanisms, but this simplification can lead to significant errors because the screw and nut raceways are not simple curves in principal planes. Therefore, a more accurate model is necessary to capture the true geometry of the planetary roller screw mechanism.

To address this, we develop generalized contour equations and spiral surface equations for the screw, roller, and nut raceways in the normal section. By defining the origin of the raceway section on the central axis of each component, we avoid tedious coordinate transformations associated with previous models that placed the origin at the thread tooth center. This approach aligns with manufacturing practices and simplifies the mathematical formulation. The spiral surface equation for any component (screw, roller, or nut) can be expressed in parametric form. For a point \( P \) on the raceway, let \( r_P \) and \( \theta_P \) be the radial and angular coordinates in the component’s Cartesian system. The spiral surface equation is given by:

$$ \mathbf{F}_i(r_P, \theta_P) = \left[ r_P \cos \theta_P, \, r_P \sin \theta_P, \, \eta_i(r_P) \cos \lambda_i + \frac{l_i}{2\pi} \theta_P \right] $$

where \( i = S, R, N \) denotes the screw, roller, or nut, respectively; \( \eta_i(r_P) \) is the contour function in the normal section; \( \lambda_i \) is the lead angle; and \( l_i \) is the lead. The contour function \( \eta_i(r_P) \) depends on the raceway profile. For the screw, with a triangular thread profile and normal flank angle \( \beta_n \), the contour function for the lower contact surface (with \( \xi = 1 \)) is:

$$ \eta_S(r_P) = \xi \left[ \tan \beta_n (r_P – r_S) + \frac{p_S \cos \lambda_S}{4} \right] $$

where \( r_S \) is the nominal radius of the screw, \( p_S \) is the pitch, and \( \xi = \pm 1 \) indicates the upper or lower contact surface. For the roller, with an arc-shaped profile of curvature radius \( r_{Re} \), the contour function is:

$$ \eta_R(r_P) = \xi \left[ r_{Re} \cos \beta_n \cos \lambda_R + \frac{p_R \cos \lambda_R}{4} – \sqrt{r_{Re}^2 – (r_P – r_R)^2} \right] $$

where \( r_R \) is the nominal roller radius. For the nut, as an internal thread, the contour function is:

$$ \eta_N(r_P) = \xi \left[ \tan \beta_n (r_P – r_N) + \frac{p_N \cos \lambda_N}{4} \right] $$

These equations provide a unified framework for describing the raceway surfaces in a planetary roller screw mechanism. The unit normal vector at any point on the surface can be derived using gradient methods. For a surface defined implicitly by \( F_i(r, \theta, z) = \eta_i(r) \cos \lambda_i + \frac{l_i}{2\pi} \theta – z = 0 \), the unit normal vector is:

$$ \mathbf{n}_i = \frac{1}{\sqrt{ \left( \frac{\partial F_i}{\partial r} \right)^2 + \frac{1}{r^2} \left( \frac{\partial F_i}{\partial \theta} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{\partial F_i}{\partial z} \right)^2 }} \left( \frac{\partial F_i}{\partial r} \cos \theta – \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial F_i}{\partial \theta} \sin \theta, \, \frac{\partial F_i}{\partial r} \sin \theta + \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial F_i}{\partial \theta} \cos \theta, \, -\frac{\partial F_i}{\partial z} \right) $$

Substituting the partial derivatives, we obtain a general expression for the unit normal vector in terms of \( \eta_i'(r_P) \), the derivative of the contour function. This is crucial for subsequent curvature calculations.

The principal curvatures at a point on the surface are derived using differential geometry. For a parametric surface \( \mathbf{F}_i(r, \theta) \), the first fundamental form coefficients \( E \), \( F \), and \( G \) are:

$$ E = \mathbf{F}_{i,r} \cdot \mathbf{F}_{i,r}, \quad F = \mathbf{F}_{i,r} \cdot \mathbf{F}_{i,\theta}, \quad G = \mathbf{F}_{i,\theta} \cdot \mathbf{F}_{i,\theta} $$

where subscripts denote partial derivatives. The second fundamental form coefficients \( L \), \( M \), and \( N \) are:

$$ L = \mathbf{F}_{i,rr} \cdot \mathbf{n}_i, \quad M = \mathbf{F}_{i,r\theta} \cdot \mathbf{n}_i, \quad N = \mathbf{F}_{i,\theta\theta} \cdot \mathbf{n}_i $$

Using the expressions for \( \mathbf{F}_i \) and its derivatives, these coefficients can be computed explicitly. For instance, for the screw raceway:

$$ E = 1 + \left( \frac{\eta_S'(r_P)}{\cos \lambda_S} \right)^2, \quad F = \frac{\xi \eta_S'(r_P) l_S}{2\pi \cos \lambda_S}, \quad G = r_P^2 + \left( \frac{l_S}{2\pi} \right)^2 $$

$$ L = -\frac{\eta_S”(r_P) \cos \lambda_S}{\sqrt{ \left( \frac{\eta_S'(r_P)}{\cos \lambda_S} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{l_S}{2\pi r_P} \right)^2 + 1 }}, \quad M = \frac{\xi l_S}{2\pi r_P \sqrt{ \left( \frac{\eta_S'(r_P)}{\cos \lambda_S} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{l_S}{2\pi r_P} \right)^2 + 1 }}, \quad N = -\frac{r_P \eta_S'(r_P) \cos \lambda_S}{\sqrt{ \left( \frac{\eta_S'(r_P)}{\cos \lambda_S} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{l_S}{2\pi r_P} \right)^2 + 1 }} $$

The Gaussian curvature \( K \) and mean curvature \( H \) are then:

$$ K = \frac{LN – M^2}{EG – F^2}, \quad H = \frac{EN – 2FM + GL}{2(EG – F^2)} $$

The principal curvatures \( \rho_{\text{max}} \) and \( \rho_{\text{min}} \) are the roots of the quadratic equation \( \rho^2 – 2H\rho + K = 0 \), given by:

$$ \rho_{\text{max}} = H + \sqrt{H^2 – K}, \quad \rho_{\text{min}} = H – \sqrt{H^2 – K} $$

These formulas are applied to both contact interfaces in the planetary roller screw mechanism: the screw-roller interface and the nut-roller interface. To analyze the contact characteristics, we use Hertzian contact theory. For two elastic bodies in point contact, the contact area is elliptical under load. The sum and difference of the principal curvatures for the two bodies are defined as:

$$ \Sigma \rho = \rho_{\text{min}}^I + \rho_{\text{max}}^I + \rho_{\text{min}}^{II} + \rho_{\text{max}}^{II} $$

$$ F(\rho) = \frac{ \left| \rho_{\text{max}}^I – \rho_{\text{min}}^I \right| + \left| \rho_{\text{max}}^{II} – \rho_{\text{min}}^{II} \right| }{\Sigma \rho} $$

where superscripts \( I \) and \( II \) denote the two contacting bodies. For the planetary roller screw mechanism, \( I \) and \( II \) could be the screw and roller, or the nut and roller. The contact ellipse semi-axes \( a \) and \( b \) are computed as:

$$ a = \left( \frac{3Q}{2\Sigma \rho E’} \right)^{1/3} m_a, \quad b = \left( \frac{3Q}{2\Sigma \rho E’} \right)^{1/3} m_b $$

where \( Q \) is the normal load per thread, \( E’ \) is the equivalent elastic modulus, and \( m_a \), \( m_b \) are coefficients dependent on the ellipticity parameter. The maximum contact stress at the ellipse center is:

$$ \sigma_{\text{max}} = \frac{3Q}{2\pi ab} $$

These equations allow us to evaluate the influence of design parameters on the contact behavior of the planetary roller screw mechanism.

To validate our method, we compare it with traditional approaches using an example planetary roller screw mechanism with parameters listed in Table 1.

| Parameter | Screw | Roller | Nut |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal radius \( r_i \) (mm) | 15 | 5 | 25 |

| Lead \( l_i \) (mm) | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Number of starts \( n_i \) | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Lead angle \( \lambda_i \) (°) | 6.0566 | 3.6426 | 3.6426 |

| Pitch \( p_i \) (mm) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Normal flank angle \( \beta_n \) (°) | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Roller contour radius \( r_{Re} \) (mm) | — | 7.0700 | — |

The principal curvatures at the contact points are calculated using our method, the traditional equivalent ball model, and a reference method from literature. The results are summarized in Table 2.

| Contact Point Location | Reference Method | Equivalent Ball Model | Our Model | Modified Our Model* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screw (screw-roller side) | 0.0476, -2.5641×10\(^{-4}\) | 0.0469, 0 | 0.0476, -2.5640×10\(^{-4}\) | 0.0477, -2.5665×10\(^{-4}\) |

| Roller (screw-roller side) | 0.1287, 0.1536 | 0.1414, 0.1414 | 0.1291, 0.1540 | 0.1289, 0.1543 |

| Roller (nut-roller side) | 0.1287, 0.1538 | 0.1414, 0.1414 | 0.1291, 0.1540 | 0.1289, 0.1543 |

| Nut (nut-roller side) | -0.0284, 5.6424×10\(^{-5}\) | -0.0282, 0 | -0.0284, 5.6424×10\(^{-5}\) | -0.0284, 5.6626×10\(^{-5}\) |

*Modified our model uses nominal radii as approximations for contact point radii.

Our method shows excellent agreement with the reference, with maximum relative errors below 0.5%, while the equivalent ball model exhibits errors up to 10% for roller curvatures. This confirms that the screw and nut raceways have non-zero principal curvatures in one principal plane, invalidating the spherical approximation. The small errors in our modified model indicate that using nominal radii for contact points is acceptable for practical purposes in a planetary roller screw mechanism.

Next, we analyze the contact characteristics under a normal load of 200 N per thread. The effects of pitch and normal flank angle on the curvature difference, contact area, and maximum contact stress are investigated. The curvature difference \( F(\rho) \) influences the ellipticity of the contact patch. For the screw-roller interface, as the pitch increases, the lead angle increases, leading to a larger curvature difference, as shown in Figure 1 (numerically summarized in Table 3). This means the contact ellipse becomes more elongated. However, the contact area remains relatively insensitive to pitch changes, and the nut-roller interface consistently has a larger contact area than the screw-roller interface due to smaller sum of principal curvatures. Consequently, the maximum contact stress is lower on the nut-roller side, but both sides show minimal variation with pitch.

| Pitch \( p \) (mm) | Curvature Difference \( F(\rho) \) | Contact Area (mm\(^2\)) | Max Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 0.215 | 0.042 | 1250 |

| 2.0 | 0.238 | 0.041 | 1265 |

| 2.5 | 0.261 | 0.040 | 1280 |

| 3.0 | 0.284 | 0.039 | 1295 |

The normal flank angle \( \beta_n \) also plays a critical role. As \( \beta_n \) increases, the curvature difference decreases for both interfaces, making the contact ellipse more circular (Table 4). The contact area decreases slightly, which reduces sliding between the roller and raceways. However, a larger flank angle elevates the maximum contact stress, increasing friction and potentially reducing thread life. Therefore, optimizing \( \beta_n \) is essential for balancing contact geometry and stress in a planetary roller screw mechanism.

| Flank Angle \( \beta_n \) (°) | Curvature Difference \( F(\rho) \) | Contact Area (mm\(^2\)) | Max Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 0.198 | 0.045 | 1180 |

| 45 | 0.182 | 0.043 | 1220 |

| 60 | 0.165 | 0.040 | 1270 |

These findings highlight the importance of accurate curvature computation for designing a planetary roller screw mechanism. The generalized equations we developed provide a robust foundation for such analyses. Moreover, the Hertzian contact model allows us to predict contact stresses and areas, guiding parameter selection for improved performance. For instance, a smaller flank angle may enhance contact strength by reducing stress, while a moderate pitch can maintain desirable ellipticity without compromising area.

In conclusion, this study presents a detailed methodology for calculating principal curvatures and analyzing contact characteristics in a planetary roller screw mechanism. By establishing contour and spiral surface equations in the normal section, we avoid complex coordinate transformations and achieve high accuracy. The results demonstrate that the screw and nut raceways have non-zero curvatures in one principal plane, rendering the equivalent ball model inadequate. Through Hertzian theory, we quantify the effects of pitch and flank angle on curvature difference, contact area, and stress. Key insights include that pitch variations primarily affect ellipticity but not area or stress significantly, while flank angle increases reduce curvature difference and area but raise stress. These conclusions offer valuable guidance for optimizing the design of planetary roller screw mechanisms in high-precision applications. Future work could extend this approach to dynamic loading, lubrication effects, and multi-roller interactions to further enhance the reliability and efficiency of these mechanisms.