In the evolving landscape of high-performance mechanical transmission systems, the demand for components that can operate under extreme conditions of speed, load, and precision has never been greater. As an integral part of this advancement, the planetary roller screw has emerged as a pivotal technology. Unlike traditional ball screws, the planetary roller screw offers superior load-bearing capacity, extended service life, higher acceleration capabilities, and the potential for finer leads, making it indispensable in aerospace, defense, robotics, and heavy machinery applications. However, the manufacturing of large-diameter planetary roller screws poses significant challenges, primarily due to reliance on subtractive machining processes that are inefficient, wasteful, and detrimental to mechanical properties. In this article, I explore innovative radial forging techniques as a solution to these limitations, delving into the principles, parametric relationships, and comparative analyses of two distinct forging methodologies. The focus is on leveraging plastic forming to enhance the performance and sustainability of planetary roller screw production, with implications for a broader range of threaded components.

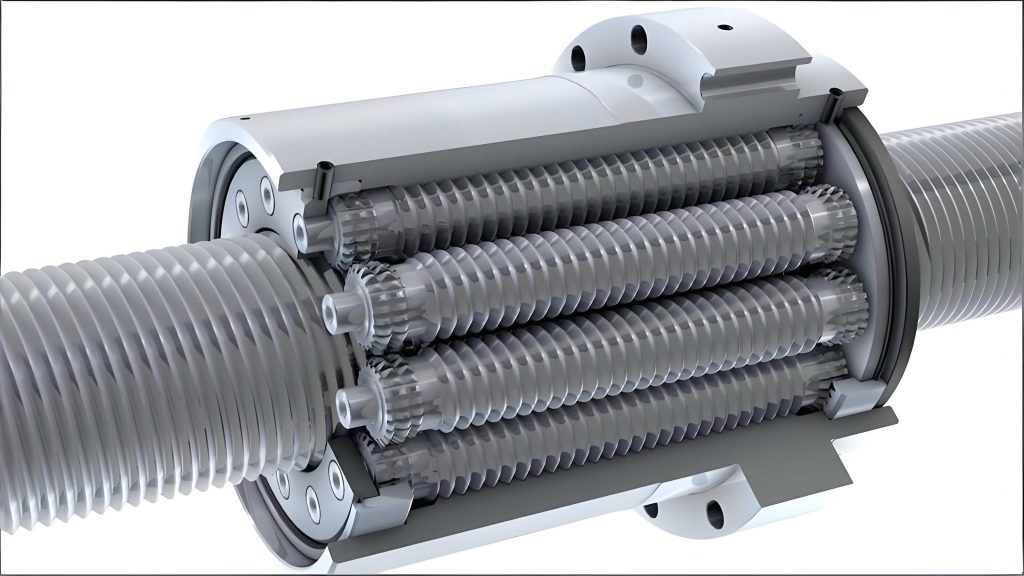

The planetary roller screw mechanism, as illustrated, consists of a central screw, multiple rollers arranged in a planetary configuration, and a nut. This design distributes loads across numerous contact points, reducing stress concentrations and enabling high torque transmission. Despite its advantages, the production of large-diameter planetary roller screws—typically those exceeding 45 mm—has been dominated by machining methods such as turning or grinding. These processes involve material removal, which severs metal fibers, compromises surface integrity, and results in substantial material waste. Moreover, machining is time-consuming and costly, hindering the scalability of planetary roller screw applications in heavy-duty contexts. Consequently, there is a pressing need for alternative manufacturing approaches that align with green manufacturing principles, emphasizing efficiency, material conservation, and enhanced mechanical properties through controlled plastic deformation.

Radial forging, a progressive forming technique where multiple dies (or hammer heads) simultaneously apply radial forces to a workpiece, presents a promising avenue. This method involves localized, incremental deformation, allowing for the shaping of complex geometries like threads without chip formation. In this analysis, I propose two radial forging variants tailored for large-diameter planetary roller screws: continuous feeding radial forging and intermittent feeding radial forging. Both methods aim to transform cylindrical blanks into precision threads through plastic flow, but they differ fundamentally in workpiece kinematics and process dynamics. By examining these techniques, I aim to establish a framework for optimizing the fabrication of planetary roller screws, deriving mathematical models that relate tool geometry, motion parameters, and product specifications. The discussion is structured around the forming principles, kinematic equations, comparative evaluations, and potential extensions to other threaded parts, with an emphasis on practical implementation and performance benefits.

Fundamentals of Radial Forging for Threaded Components

Radial forging is characterized by the synchronized action of multiple forging dies arranged radially around a workpiece. These dies strike the workpiece in rapid succession, inducing plastic deformation through compressive stresses. For thread formation, the dies are machined with internal thread profiles that collectively mimic the external thread of the target planetary roller screw. The process is inherently incremental, reducing forging loads compared to bulk forming and minimizing springback effects. Key advantages include improved grain structure alignment, increased surface hardness due to work hardening, and reduced material waste. In the context of planetary roller screws, radial forging can be adapted to handle large diameters by modulating feed rates, rotational speeds, and die configurations. The core challenge lies in synchronizing workpiece motion with die movements to ensure thread continuity and accuracy, which I address through geometric and kinematic analyses for both continuous and intermittent feeding approaches.

The mathematical modeling of radial forging for planetary roller screws involves parameters such as lead (P), number of thread starts (n), die number (N), feed distances, and rotational angles. These parameters are interrelated through equations that govern thread engagement and forming completeness. For instance, the lead of the planetary roller screw determines the axial advance per revolution, while the number of dies influences the circumferential coverage per forging cycle. I derive these relationships systematically, using LaTeX-formatted equations to clarify dependencies. Additionally, tables are employed to summarize parameter ranges and process constraints, facilitating a clear comparison between the two forging methods. The subsequent sections delve into the specifics of each method, starting with continuous feeding radial forging.

Continuous Feeding Radial Forging for Planetary Roller Screws

In continuous feeding radial forging, the workpiece undergoes simultaneous rotation and axial translation during the intervals between die strikes. This method ensures a seamless thread formation by progressively deforming the material along the screw axis. The dies, which have threaded profiles, engage the workpiece incrementally, with each forging cycle covering a small segment of the thread helix. The kinematic relationship between axial feed and rotation is critical to maintaining thread pitch accuracy. Let the axial feed distance per forging interval be denoted as \( l_c \), and the corresponding rotational angle as \( \theta_c \). For a planetary roller screw with lead \( P \), the following equation must hold to ensure thread continuity:

$$ l_c = \frac{\theta_c}{2\pi} P $$

This equation implies that the feed distance is proportional to the rotational angle scaled by the lead. Furthermore, if the workpiece rotates with an angular velocity \( \omega \) and translates axially at velocity \( v \), the relationship during continuous feeding is:

$$ v = \frac{P \omega}{2\pi} $$

This ensures that the helix trajectory matches the die profile. The rotational angle per forging interval, \( \theta_c \), must be selected within a range that prevents overlapping or gaps in thread formation. Given \( N \) dies, the angle should satisfy:

$$ 0 < \theta_c < \frac{2\pi}{N} $$

This constraint arises because each die forges a distinct circumferential segment; excessive rotation could cause re-forging of the same area, while insufficient rotation might leave unformed zones. For a typical setup with four dies (\( N = 4 \)), \( \theta_c \) would be less than 90 degrees. The process sequence involves initial forging over a portion of the screw length (e.g., 2/3 to 3/4), followed by repositioning of the workpiece via a manipulator to complete the remaining section. This minimizes handling interruptions and ensures full thread coverage.

The die design for continuous feeding radial forging features a threaded cavity with an effective length \( l_a \). This length must accommodate the feed distance \( l_c \), but since \( l_c \) is small, \( l_a \) can be relatively short, reducing die complexity and cost. However, precision in die alignment and strike synchronization is paramount to avoid thread distortions. The following table summarizes key parameters and their interrelationships for continuous feeding radial forging of planetary roller screws:

| Parameter | Symbol | Relationship/Constraint | Typical Value Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead of Planetary Roller Screw | \( P \) | Determined by application requirements | 5–50 mm |

| Number of Dies | \( N \) | Typically 2, 3, 4, or 6 | 4 (common) |

| Rotational Angle per Interval | \( \theta_c \) | \( 0 < \theta_c < \frac{2\pi}{N} \) | 10–80 degrees |

| Axial Feed per Interval | \( l_c \) | \( l_c = \frac{\theta_c}{2\pi} P \) | 0.1–2 mm |

| Angular Velocity | \( \omega \) | \( \omega = \frac{2\pi v}{P} \) | 0.1–10 rad/s |

| Axial Feed Velocity | \( v \) | \( v = \frac{P \omega}{2\pi} \) | 0.5–20 mm/s |

| Die Effective Length | \( l_a \) | \( l_a > l_c \) | 5–30 mm |

The continuous feeding method is characterized by low forging loads due to small deformation zones, making it suitable for materials with moderate strength. However, it requires precise control systems to maintain the exact coordination between rotation and feed, especially for large-diameter planetary roller screws where errors can accumulate. Additionally, the process time may be longer compared to intermittent feeding, as the incremental advances are minimal. Nonetheless, this method offers flexibility in handling various thread geometries and is less restrictive in terms of screw specifications.

Intermittent Feeding Radial Forging for Planetary Roller Screws

Intermittent feeding radial forging adopts a different approach: the workpiece rotates but does not translate axially during forging cycles. Instead, after a segment is fully forged, the workpiece rapidly advances axially by a distance \( l_i \) and rotates by a specific angle \( \phi \) to align the next unformed section with the dies. This method is akin to a stepwise forming process, where each forging operation covers a discrete length of the planetary roller screw. The axial feed distance \( l_i \) is constrained by the effective length of the dies \( l_a \), as the entire forged segment must fit within the die cavity. Thus, the condition is:

$$ l_i \leq l_a $$

To ensure thread continuity between forged segments, the workpiece must rotate during or after the rapid advance. The required rotation angle \( \phi \) is derived from the lead and feed distance:

$$ \phi = \frac{l_i}{P} \cdot 2\pi $$

During the forging phase, the workpiece rotates continuously without axial movement. The rotational angle per forging cycle, \( \theta_i \), must align with the thread starts to avoid mismatches. For a planetary roller screw with \( n \) thread starts, \( \theta_i \) should be:

$$ \theta_i = \frac{2\pi}{n} $$

This ensures that each die strike corresponds to a distinct thread ridge. However, to prevent forging dead zones—areas that remain undeformed due to die spacing—the rotational angle must also satisfy:

$$ \theta_i \neq \frac{2\pi}{N} $$

If \( \theta_i \) equals \( 2\pi / N \), the dies would repeatedly strike the same circumferential points, leaving gaps. Therefore, \( \theta_i \) should be chosen such that it is not an integer multiple of the die spacing angle. For example, with \( N = 4 \) and a single-start planetary roller screw (\( n = 1 \)), \( \theta_i = 360^\circ \), which clearly violates the inequality, necessitating adjustments such as using a multi-start design or modifying die timing. In practice, for multi-start planetary roller screws, \( n \) and \( N \) should be coprime to ensure full coverage.

The intermittent feeding process involves forging a substantial portion of the screw length in one go, leading to larger plastic deformation zones and higher forging loads compared to continuous feeding. This method is more efficient in terms of cycle time, as the rapid advances reduce idle periods. The die design requires a longer threaded length \( l_a \) to accommodate \( l_i \), increasing die manufacturing complexity. Below is a table summarizing the parameters for intermittent feeding radial forging of planetary roller screws:

| Parameter | Symbol | Relationship/Constraint | Typical Value Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead of Planetary Roller Screw | \( P \) | Application-dependent | 5–50 mm |

| Number of Thread Starts | \( n \) | Integral to screw design | 1–6 |

| Number of Dies | \( N \) | Commonly 4 or 6 | 4 |

| Axial Feed per Intermittent Move | \( l_i \) | \( l_i \leq l_a \) | 10–100 mm |

| Rotation Angle for Alignment | \( \phi \) | \( \phi = \frac{l_i}{P} \cdot 2\pi \) | 30–720 degrees |

| Rotational Angle per Forging Cycle | \( \theta_i \) | \( \theta_i = \frac{2\pi}{n} \) | 60–360 degrees |

| Die Effective Length | \( l_a \) | \( l_a \geq l_i \) | 20–150 mm |

| Forging Load | \( F \) | Estimated via plasticity models | High (e.g., 10–100 MN) |

The intermittent feeding method is particularly advantageous for high-volume production of planetary roller screws with consistent geometries, as it reduces process time and simplifies motion control during forging phases. However, it imposes limitations on the screw specifications; for instance, the relationship between \( n \) and \( N \) must be carefully managed to avoid incomplete forming. Additionally, the higher forging loads necessitate robust machinery and may restrict its use to materials with lower flow stresses or require intermediate annealing steps. Integration with induction heating systems can mitigate this by locally softening the workpiece, expanding the range of forgeable materials for planetary roller screws.

Comparative Analysis of Continuous and Intermittent Feeding Radial Forging

To elucidate the trade-offs between continuous and intermittent feeding radial forging for planetary roller screws, I conduct a detailed comparison based on multiple criteria: process kinematics, forging loads, efficiency, geometric flexibility, and control requirements. Both methods share a common die structure—multiple hammer heads with threaded profiles that coalesce into an internal thread form—but diverge in implementation. The comparative insights are synthesized into a table below, followed by a discussion of key equations and implications.

| Criterion | Continuous Feeding Radial Forging | Intermittent Feeding Radial Forging |

|---|---|---|

| Workpiece Motion | Simultaneous rotation and axial feed during forging intervals | Rotation only during forging; intermittent axial feed and rotation between cycles |

| Axial Feed Distance | Small: \( l_c = \frac{\theta_c}{2\pi} P \) | Large: \( l_i \leq l_a \) |

| Rotational Angle per Cycle | \( \theta_c \), with \( 0 < \theta_c < \frac{2\pi}{N} \) | \( \theta_i = \frac{2\pi}{n} \), with \( \theta_i \neq \frac{2\pi}{N} \) |

| Die Effective Length | Short (can be less than feed distance accumulation) | Long (must accommodate \( l_i \)) |

| Forging Loads | Lower due to small deformation zones | Higher due to larger contact areas |

| Process Efficiency | Lower (slower due to incremental feeds) | Higher (faster due to batch forging) |

| Control Precision | High (requires precise sync of rotation and feed) | Moderate (focus on positioning between cycles) |

| Geometric Flexibility | High (suitable for various leads and starts) | Limited by \( n \) and \( N \) compatibility |

| Material Suitability | Better for high-strength materials | May require heating for tough materials |

| Applications | Custom or small-batch planetary roller screws | Mass production of standard planetary roller screws |

The forging load differential can be quantified using plasticity theory. For continuous feeding, the instantaneous deformation volume \( V_c \) is approximated as the product of feed distance \( l_c \) and the cross-sectional area of the thread groove. The forging force \( F_c \) scales with flow stress \( \sigma_f \) and area:

$$ F_c \approx \sigma_f \cdot A_c $$

where \( A_c \) is the contact area per die, which is small due to incremental feed. In contrast, for intermittent feeding, the deformation volume \( V_i \) is larger, proportional to \( l_i \), leading to:

$$ F_i \approx \sigma_f \cdot A_i $$

with \( A_i > A_c \). Empirical studies suggest \( F_i \) can be an order of magnitude greater than \( F_c \), necessitating heavier equipment for intermittent forging. The efficiency comparison can be expressed in terms of throughput \( Q \), defined as formed length per unit time. For continuous feeding, \( Q_c = v \), while for intermittent feeding, \( Q_i = l_i / t_i \), where \( t_i \) is the cycle time including forging and rapid advance. Typically, \( Q_i > Q_c \) for large-diameter planetary roller screws, making intermittent feeding preferable for high-volume scenarios.

Geometric constraints arise from the equations governing rotational angles. In continuous feeding, the condition \( 0 < \theta_c < 2\pi/N \) is relatively easy to satisfy for any planetary roller screw lead, as \( \theta_c \) can be adjusted. However, in intermittent feeding, the requirement \( \theta_i = 2\pi/n \) and \( \theta_i \neq 2\pi/N \) imposes restrictions on the combination of thread starts and die number. For instance, a single-start planetary roller screw (\( n=1 \)) with \( N=4 \) would have \( \theta_i = 360^\circ \), which equals \( 2\pi/N \) when \( N=1 \) but not for \( N=4 \); however, since \( 360^\circ = 2\pi \), and \( 2\pi/N = \pi/2 \) for \( N=4 \), they are not equal, so it may be acceptable, but care is needed to avoid common multiples. A general rule is that \( n \) and \( N \) should be coprime to ensure uniform coverage, which limits design options for intermittent forging.

Control precision is another differentiator. Continuous feeding demands real-time coordination between rotational and axial drives, often requiring closed-loop feedback systems to maintain the helix trajectory. Errors in \( \theta_c \) or \( l_c \) can lead to pitch deviations or thread discontinuities. Intermittent feeding, while simpler during forging (only rotation), requires accurate positioning during rapid advances, with tolerances on \( l_i \) and \( \phi \) to ensure thread alignment. Both methods benefit from advanced CNC systems, but continuous feeding is more susceptible to dynamic errors due to continuous motion.

Mathematical Modeling and Parametric Optimization

To deepen the analysis, I derive comprehensive models for both radial forging methods, incorporating material behavior, die geometry, and process kinematics. These models facilitate optimization of parameters for manufacturing large-diameter planetary roller screws. The thread profile on a planetary roller screw is typically trapezoidal or modified to handle heavy loads. The die profile must mirror this, with clearance angles to facilitate material flow. For a trapezoidal thread with flank angle \( \alpha \), root diameter \( d_r \), and crest diameter \( d_c \), the cross-sectional area of the thread groove \( A_g \) can be approximated as:

$$ A_g = \frac{P}{2} \left( \frac{d_c – d_r}{2} \tan \alpha \right) $$

This area influences forging pressures. In radial forging, the dies apply pressure to form this groove incrementally. Using slab analysis, the forging pressure \( p \) for a cylindrical workpiece of diameter \( D \) under radial compression can be estimated as:

$$ p = \sigma_f \left(1 + \frac{\mu D}{4 h}\right) $$

where \( \mu \) is the friction coefficient, and \( h \) is the instantaneous height of the deformation zone (related to feed distance). For continuous feeding, \( h \) is small, reducing the friction term and thus \( p \). For intermittent feeding, \( h \) is larger, increasing \( p \) and total force.

The total forging energy \( E \) for a planetary roller screw of length \( L \) can be integrated over the process. For continuous feeding, with constant \( v \) and \( \omega \), the energy is:

$$ E_c = \int_0^{L/v} F_c(t) \, v \, dt $$

Assuming steady-state, \( E_c \approx F_c L \). For intermittent feeding, with discrete cycles of number \( L/l_i \), the energy is:

$$ E_i = \sum_{k=1}^{L/l_i} F_i \, \delta_i $$

where \( \delta_i \) is the deformation per cycle. Typically, \( E_i > E_c \) due to higher forces, but the shorter process time may reduce overall energy consumption per part when considering machine efficiency.

Optimization involves minimizing forging loads while maximizing throughput. For continuous feeding, the objective is to select \( \theta_c \) and \( v \) to reduce \( F_c \) without compromising thread quality. This can be formulated as a constrained optimization problem:

$$ \text{Minimize } F_c(\theta_c, v) \text{ subject to } l_c = \frac{\theta_c}{2\pi} P, \quad 0 < \theta_c < \frac{2\pi}{N} $$

Similarly, for intermittent feeding, the goal is to choose \( l_i \) and \( n \) to minimize \( F_i \) while ensuring formability:

$$ \text{Minimize } F_i(l_i, n) \text{ subject to } l_i \leq l_a, \quad \theta_i = \frac{2\pi}{n}, \quad \theta_i \neq \frac{2\pi}{N} $$

These optimizations can be solved numerically, with results tailored to specific planetary roller screw dimensions. The table below presents an example optimization outcome for a large-diameter planetary roller screw with \( D = 60 \, \text{mm} \), \( P = 10 \, \text{mm} \), and material flow stress \( \sigma_f = 600 \, \text{MPa} \):

| Parameter | Continuous Feeding Optimal | Intermittent Feeding Optimal |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Dies (\( N \)) | 4 | 4 |

| Rotational Angle (\( \theta_c \) or \( \theta_i \)) | 45° (\( \pi/4 \)) | 180° (\( \pi \)) for \( n=2 \) |

| Axial Feed (\( l_c \) or \( l_i \)) | 1.25 mm | 50 mm |

| Forging Force (per die) | ~50 kN | ~500 kN |

| Throughput (\( Q \)) | 8 mm/s (assumed \( v \)) | 100 mm/s (effective) |

| Energy per Unit Length | 6.25 kJ/m | 10 kJ/m |

These results highlight the trade-offs: continuous forging yields lower forces and energy but slower production, while intermittent forging offers speed at the cost of higher loads. The choice depends on production volume, material properties, and equipment capabilities for planetary roller screw manufacturing.

Extension to Other Threaded Components and Advanced Techniques

The radial forging methodologies developed for planetary roller screws are not limited to this component alone; they can be adapted to a wide array of large-diameter threaded parts, such as lead screws, ball screw shafts, and power transmission screws. The underlying principles of synchronized die action and controlled workpiece motion remain applicable, with modifications to die profiles and kinematic equations based on thread geometry. For instance, for Acme threads commonly used in lead screws, the flank angle \( \alpha \) differs, altering the forging pressure calculations. The general equations for feed and rotation can be extended as follows, where \( P \) is the lead, and \( m \) is a thread form factor (e.g., \( m=1 \) for standard threads):

$$ \text{Axial feed per interval} = m \cdot \frac{\theta}{2\pi} P $$

This adaptability makes radial forging a versatile process for high-performance threaded components beyond planetary roller screws.

To enhance the applicability of radial forging for difficult-to-form materials, such as high-strength alloys used in aerospace planetary roller screws, I propose integrating in-process heating. Induction heating can be applied locally to the deformation zone, reducing flow stress and forging loads. The temperature rise \( \Delta T \) can be estimated from energy input:

$$ \Delta T = \frac{Q_{\text{heat}}}{\rho c_p V} $$

where \( Q_{\text{heat}} \) is the heat energy, \( \rho \) is density, \( c_p \) is specific heat, and \( V \) is the heated volume. By controlling \( \Delta T \), materials like titanium or tool steel can be forged without excessive die wear or cracking. This hybrid approach combines the benefits of hot forging (lower forces) with cold forging (precision and strength), ideal for heavy-duty planetary roller screws.

Future advancements in radial forging for planetary roller screws may involve adaptive control systems using real-time monitoring of forging forces and thread geometry. Sensors can detect variations in material properties or die wear, adjusting feed rates or rotational speeds accordingly. Additionally, multi-stage forging processes could be employed, where a rough thread is formed initially via intermittent feeding, followed by a finishing pass with continuous feeding to achieve high accuracy. Such strategies would further optimize the manufacturing of planetary roller screws for critical applications.

Conclusion

In this comprehensive exploration, I have examined radial forging as a transformative plastic forming technique for large-diameter heavy-duty planetary roller screws. The analysis centered on two distinct approaches: continuous feeding radial forging and intermittent feeding radial forging. For each method, I elucidated the forming principles, derived kinematic and geometric relationships using LaTeX-formulated equations, and summarized key parameters in tables for clarity. The continuous feeding method involves simultaneous rotation and axial feed during forging intervals, characterized by low forging loads and high geometric flexibility, albeit with lower efficiency and stringent control requirements. In contrast, intermittent feeding employs discrete forging cycles with rapid advances, offering higher throughput but imposing constraints on thread starts and die numbers, along with significantly higher forging forces.

The comparative assessment reveals that the choice between these methods depends on production volume, material characteristics, and desired mechanical properties for planetary roller screws. Continuous feeding is advantageous for custom or small-batch production where flexibility and reduced loads are prioritized, while intermittent feeding suits mass production of standardized planetary roller screws where speed is critical. Both methods surpass traditional machining in terms of material utilization, mechanical performance enhancement, and alignment with sustainable manufacturing goals.

Furthermore, the mathematical models and optimization frameworks presented here provide a foundation for process design, enabling manufacturers to tailor radial forging parameters for specific planetary roller screw specifications. The extension to other threaded components underscores the versatility of this technology, with potential adaptations for various industrial applications. As the demand for high-performance transmission systems grows, radial forging stands out as a key enabler for producing robust, precision planetary roller screws that meet the challenges of high-speed, heavy-load, and high-precision environments. Future work should focus on experimental validation, die life improvement, and integration with smart manufacturing systems to fully realize the potential of radial forging for advanced threaded parts.