In my extensive research into hydraulic pump technologies, I have focused on addressing a fundamental limitation of conventional gear pumps: the persistent issue of unbalanced radial forces. These forces, generated during operation, lead to shaft deformation, increased wear, and reduced bearing life, especially at higher pressures. My innovative approach involves integrating the principles of strain wave gear transmission into gear pump design, creating what I term the strain wave gear pump. This design inherently balances radial hydraulic pressures by symmetrically positioning inlet and outlet ports, thereby significantly enhancing durability and performance. The strain wave gear mechanism, known for its high torque density and precision, offers unique advantages when applied to pumping applications, making it a promising solution for demanding industrial, agricultural, and mobile machinery.

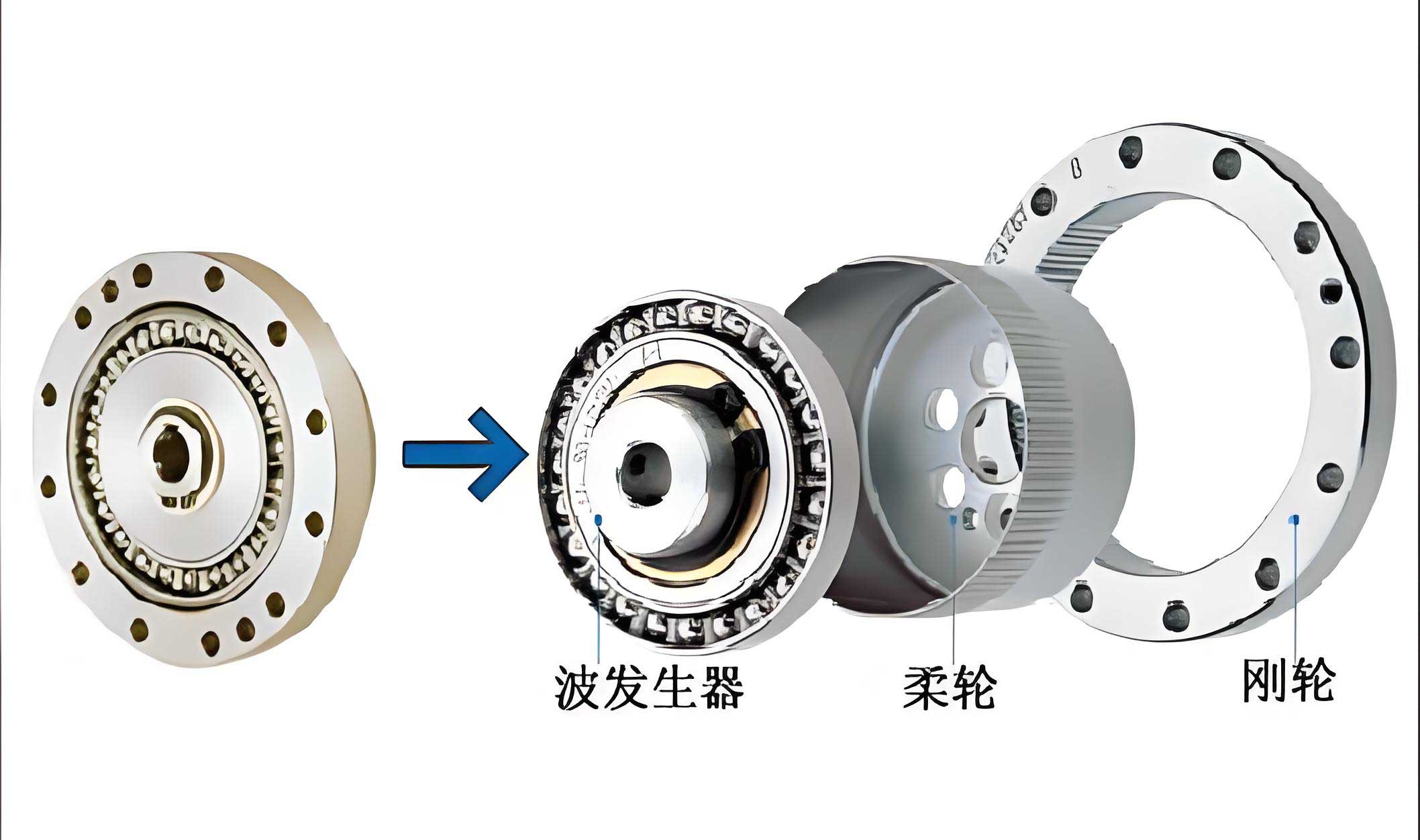

The core operating principle of the strain wave gear pump revolves around three key components: a rigid ring (often called the circular spline), a flexible ring (the flexspline), and a wave generator. In my design, a pair of partition plates is installed between the rigid and flexible rings to effectively separate the low-pressure suction chamber from the high-pressure discharge chamber. The wave generator is typically held stationary. When the rigid ring is driven to rotate, it induces a controlled elastic deformation in the flexible ring. This deformation wave propagates, causing the teeth of the flexible ring to engage and disengage with those of the rigid ring in a traveling motion. As teeth disengage at the inlet region, the volume between them increases, creating a vacuum that draws hydraulic fluid into the pump. The fluid is then transported within the tooth spaces to the outlet region, where the teeth re-engage, reducing the volume and pressurizing the fluid for discharge. This continuous process ensures a steady flow.

This configuration is pivotal for the strain wave gear pump’s success. The symmetrical placement of fluid ports relative to the wave generator’s axes means that the radial fluid pressure forces on the flexible ring are largely self-canceling. This direct mitigation of the unbalanced radial force problem, which plagues traditional external gear pumps, is the primary merit of my strain wave gear pump concept. It translates to lower bearing loads, minimized deflection, reduced friction, and consequently, a longer operational lifespan even under high-pressure conditions.

Central to the performance of any gear pump, including the strain wave variant, is the geometry of its teeth. Therefore, a critical part of my research has been the selection and mathematical definition of the optimal tooth profile. The profile influences factors such as manufacturing complexity, contact stress, efficiency, noise, and the ability to form sealing lines and lubricating films. For strain wave gears, the profile must additionally accommodate the periodic elastic deformation of the flexible ring without losing proper meshing characteristics or inducing excessive stress.

| Profile Type | Geometric Description | Primary Advantages | Primary Challenges | Suitability for Strain Wave Gear Pumps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Involute | Curve traced by a point on a taut string unwinding from a base circle. Characterized by a constant pressure angle along the profile. | Simplified manufacturing using standard gear cutting tools. Conjugate action ensures smooth transmission. Insensitive to small center distance variations. | In a strain wave gear, simultaneous multi-tooth engagement under load often results in partial, edge-contact, hindering optimal load sharing and fluid film formation. Can lead to high contact stresses at specific points. | Moderate. A good baseline but requires modification for optimal performance in a strain wave gear pump. |

| Involute Narrow-Slot | A variant where the tooth thickness at the root circle is significantly greater than the slot width. | Provides high bending strength at the tooth root. Common in traditional harmonic drives for its工艺 simplicity. | The relatively narrow slot may limit fluid volume per tooth and potentially increase flow pulsation. Engagement conditions similar to standard involute. | Acceptable, but not optimal for pumping efficiency and contact. |

| Involute Wide-Slot | A variant involving profile modification where the slot width at the root approaches or exceeds the tooth thickness, often with reduced addendum. | Reduces tooth height, which can lower bending stress and root interference risks. Provides larger inter-tooth volume for fluid transfer. | Design and machining are more complex than standard involutes. Requires precise modification calculations. | Good. The larger fluid volume is beneficial for pump displacement. |

| Modified (Corrected) Involute | A standard involute profile that has been intentionally altered, typically by tip and/or root relief, or by applying a topological modification (lead crowning, profile slope). | Optimizes the contact pattern under load, promoting more uniform load distribution across multiple engaged teeth. Facilitates the formation of a hydrodynamic lubricant film. Reduces noise and stress concentrations. | Requires sophisticated design analysis and may involve non-standard or customized machining processes. | Most Suitable. The modifications directly address the partial engagement issue inherent in strain wave gearing, making it ideal for the dual function of torque transmission and fluid displacement in a pump. |

Based on my analysis, I conclude that a properly modified involute tooth profile represents the most balanced choice for the strain wave gear pump. The modification is essential to transform the theoretical line contact of conjugate involutes into a favorable area contact under the specific deformed state of the flexible ring. This ensures smoother operation, higher load capacity, and better conditions for the hydraulic fluid within the pumping chambers. The mathematical derivation of the exact tooth profile curves, accounting for the wave generator’s shape and the flexible ring’s deformation, is therefore fundamental.

To derive the precise tooth profile curve equations for both the rigid and flexible rings of the strain wave gear pump, I establish a kinematic model with the following simplifying assumptions, which are standard in initial strain wave gear analysis yet sufficiently accurate for pump design purposes:

- The neutral curve (midline) of the flexible ring’s thin-walled body experiences pure bending without membrane stretching or contraction; its length remains constant.

- Tooth profiles on the flexible ring are considered rigid; deformation occurs only in the ring body between teeth.

- Deformation is confined to the cross-sectional plane, meaning any longitudinal section of a tooth remains planar during motion.

- The form of the wave generator is fixed, and the resulting deflection of the flexible ring’s neutral curve is constant during steady-state operation.

I define a global coordinate system $\{xoy\}$ fixed to the wave generator, with origin $o$ at its geometric center. The $y$-axis is aligned with the major axis of the generator’s elliptical profile. Let the parametric equation of this ellipse (representing the inner surface guiding the flexible ring) be:

$$ x_w = b \sin t, \quad y_w = a \cos t $$

where $a$ and $b$ are the semi-major and semi-minor axes, respectively, and $t$ is a parameter. Its polar form relative to $o$ is:

$$ \rho = \frac{ab}{\sqrt{a^2 \sin^2 \phi_H + b^2 \cos^2 \phi_H}} $$

Here, $(\rho, \phi_H)$ are the polar coordinates of a point $H$ on the ellipse.

Now, I attach a moving coordinate system $\{x_1o_1y_1\}$ to a single tooth on the flexible ring. The origin $o_1$ is located on the neutral curve of the flexible ring (denoted as curve $c$), which is offset from the inner ellipse by the wall thickness $e$. The $y_1$-axis is aligned with the symmetry axis of the tooth. Another moving system $\{x_2o_2y_2\}$ is fixed to the rigid ring, with origin $o_2$ at its rotation center and the $y_2$-axis along the symmetry line of a tooth space.

If $(x_1, y_1)$ are the coordinates of a point on the flexible ring tooth profile in its local system $\{x_1o_1y_1\}$, its coordinates $(x_1′, y_1′)$ in the global system $\{xoy\}$ are obtained by a transformation comprising a rotation and a translation:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} x_1′ \\ y_1′ \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{M}_{01} \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ y_1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

where the transformation matrix $\mathbf{M}_{01}$ is:

$$ \mathbf{M}_{01} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\psi & -\sin\psi & \rho_1 \cos\phi_1 \\ \sin\psi & \cos\psi & \rho_1 \sin\phi_1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

Similarly, for a point $(x_2, y_2)$ on the rigid ring profile in $\{x_2o_2y_2\}$, its global coordinates $(x_2′, y_2′)$ are:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} x_2′ \\ y_2′ \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{M}_{02} \begin{bmatrix} x_2 \\ y_2 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \text{with} \quad \mathbf{M}_{02} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\phi_2 & -\sin\phi_2 & 0 \\ \sin\phi_2 & \cos\phi_2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

The angles $\psi$, $\phi_1$, and $\phi_2$ are critical and are derived from the geometry of the strain wave gear assembly.

| Angle / Variable | Symbol | Definition and Derivation |

|---|---|---|

| Polar angle on ellipse | $\phi_H$ | Independent parameter defining location on wave generator surface. |

| Coordinate rotation angle | $\psi$ | Angle between global $x$-axis and local $x_1$-axis (tooth symmetry axis). For an ellipse: $$ \psi = \arctan\left( \frac{a^2}{b^2} \tan \phi_H \right) $$ This comes from the slope of the ellipse normal. |

| Radial distance to neutral curve | $\rho_1$ | Distance from global origin $o$ to point $o_1$ on the neutral curve. Using the law of cosines: $$ \rho_1 = \sqrt{e^2 + \rho^2 + 2e\rho \cos \mu} $$ where $e$ is wall thickness. |

| Angle between tooth axis and ellipse radial line | $\mu$ | $$ \mu = \psi – \phi_H $$ |

| Small correction angle | $\mu_1$ | Angle between tooth axis and neutral curve radial line $\rho_1$. For small $\mu$: $$ \mu_1 \approx \arcsin\left( \frac{\rho}{\rho_1} \sin \mu \right) \approx \frac{\rho}{\rho_1} \sin \mu $$ |

| Angle between radial lines | $\gamma$ | $$ \gamma = \mu – \mu_1 $$ |

| Polar angle of neutral curve point | $\phi_1$ | $$ \phi_1 = \phi_H + \gamma $$ |

| Rigid ring rotation angle | $\phi_2$ | Related to the flexible ring rotation. If the flexible ring rotates by an angle $\phi$, and tooth numbers are $z_1$ (flexible) and $z_2$ (rigid), then: $$ \phi_2 = \frac{z_1}{z_2} \phi $$ This ensures correct meshing kinematics. |

With the kinematic relationships established, I now define the tooth profile itself. I have selected a modified involute curve. For derivation ease, I first consider an unmodified involute in a local coordinate system $\{x_0o_0y_0\}$ attached to the gear blank, with the $y_0$-axis passing through the center of the tooth. The parametric equations for the left flank of a standard involute are:

$$ x_0 = r_b (\sin \lambda – \lambda \cos \alpha_0 \cos(\lambda + \alpha_0)) $$

$$ y_0 = r_b (\cos \lambda + \lambda \cos \alpha_0 \sin(\lambda + \alpha_0)) $$

Here, $r_b$ is the base circle radius ($r_b = r \cos \alpha_0$, where $r=mz/2$ is the pitch radius, $m$ is module, $z$ is tooth count, $\alpha_0$ is the tool pressure angle). The parameter $\lambda$ is the roll angle: $$ \lambda = \tan \alpha_k – \tan \alpha_0 $$ where $\alpha_k$ is the pressure angle at the point in question, varying from $\alpha_0$ at the pitch circle to a larger value at the addendum.

To account for profile shift or modification (characterized by coefficient $x$), the tooth thickness on the pitch circle changes. The half-tooth-space angle $\theta$ on the pitch circle relative to the $y_0$-axis becomes:

$$ \theta = \frac{s}{2r} = \frac{m(\pi/2 + 2x \tan \alpha_0)}{2r} = \frac{\pi + 4x \tan \alpha_0}{2z} $$

Rotating the profile by $\theta$ aligns it correctly. Thus, in a coordinate system $\{xoy\}$ aligned with the tooth’s central axis (after rotation), the left flank equations become:

$$ x = r_b [\sin(\lambda – \theta) – \lambda \cos \alpha_0 \cos(\lambda – \theta + \alpha_0)] $$

$$ y = r_b [\cos(\lambda – \theta) + \lambda \cos \alpha_0 \sin(\lambda – \theta + \alpha_0)] $$

The right flank is symmetrical:

$$ x = -r_b [\sin(\lambda – \theta) – \lambda \cos \alpha_0 \cos(\lambda – \theta + \alpha_0)] $$

$$ y = r_b [\cos(\lambda – \theta) + \lambda \cos \alpha_0 \sin(\lambda – \theta + \alpha_0)] $$

These $(x, y)$ coordinates are defined in a tooth-centric system. To obtain the profiles in the global $\{xoy\}$ system (fixed to wave generator), I apply the previously defined transformations, substituting $(x_1, y_1)$ with these involute expressions.

Therefore, the final tooth profile curve equations for the flexible ring (right flank) in the global coordinate system are:

$$ \begin{aligned}

x_1′ &= r_{b1} \left[ \sin(\psi – (\lambda_1 – \theta_1)) + \lambda_1 \cos \alpha_0 \cos(\psi – (\lambda_1 – \theta_1) + \alpha_0) \right] + \rho_1 \sin\phi_1 – r_{m1} \sin\psi \\

y_1′ &= r_{b1} \left[ \cos(\psi – (\lambda_1 – \theta_1)) – \lambda_1 \cos \alpha_0 \sin(\psi – (\lambda_1 – \theta_1) + \alpha_0) \right] + \rho_1 \cos\phi_1 – r_{m1} \cos\psi

\end{aligned} $$

For the flexible ring (left flank):

$$ \begin{aligned}

x_1′ &= r_{b1} \left[ \sin(\psi + (\lambda_1 – \theta_1)) – \lambda_1 \cos \alpha_0 \cos(\psi + (\lambda_1 – \theta_1) + \alpha_0) \right] + \rho_1 \sin\phi_1 – r_{m1} \sin\psi \\

y_1′ &= r_{b1} \left[ \cos(\psi + (\lambda_1 – \theta_1)) + \lambda_1 \cos \alpha_0 \sin(\psi + (\lambda_1 – \theta_1) + \alpha_0) \right] + \rho_1 \cos\phi_1 – r_{m1} \cos\psi

\end{aligned} $$

Here, subscript $1$ denotes flexible ring parameters ($r_{b1}$ is its base radius, $\theta_1$ its half-tooth-space angle, $\lambda_1$ its roll angle parameter). The term $r_{m1}$ is a reference radius, often the radius to the neutral curve at the tooth center, used for precise positioning.

For the rigid ring (right flank), the profile in the global system is:

$$ \begin{aligned}

x_2′ &= r_{b2} \left[ \sin(\phi_2 – (\lambda_2 – \theta_2)) + \lambda_2 \cos \alpha_0 \cos(\phi_2 – (\lambda_2 – \theta_2) + \alpha_0) \right] \\

y_2′ &= r_{b2} \left[ \cos(\phi_2 – (\lambda_2 – \theta_2)) – \lambda_2 \cos \alpha_0 \sin(\phi_2 – (\lambda_2 – \theta_2) + \alpha_0) \right]

\end{aligned} $$

For the rigid ring (left flank):

$$ \begin{aligned}

x_2′ &= -r_{b2} \left[ \sin(\phi_2 – (\lambda_2 – \theta_2)) – \lambda_2 \cos \alpha_0 \cos(\phi_2 – (\lambda_2 – \theta_2) + \alpha_0) \right] \\

y_2′ &= r_{b2} \left[ \cos(\phi_2 – (\lambda_2 – \theta_2)) – \lambda_2 \cos \alpha_0 \sin(\phi_2 – (\lambda_2 – \theta_2) + \alpha_0) \right]

\end{aligned} $$

Subscript $2$ denotes rigid ring parameters. These equations fully describe the instantaneous position of every point on the tooth profiles during the operation of the strain wave gear pump.

The power of these derived equations lies in their application for design, analysis, and optimization. By programming these parametric equations into computational software like MATLAB, Python, or specialized CAD systems, I can perform a multitude of critical analyses for the strain wave gear pump:

- Tooth Engagement Simulation: Animating the relative motion between the rigid and flexible ring teeth to visualize the meshing process throughout a full cycle of the wave generator.

- Interference Checking: Determining if the deformed flexible ring tooth profiles collide with the rigid ring teeth at any point during rotation, which is crucial for avoiding jamming and wear.

- Contact Path and Pressure Angle Analysis: Calculating the path of contact and the instantaneous pressure angle. For the strain wave gear pump, a smooth and continuous variation is desirable for stable fluid displacement and minimal vibration.

$$ \alpha_{inst} = \arctan\left( \frac{dy/d\lambda}{dx/d\lambda} \right) \text{(evaluated along the path of contact)} $$ - Sealing Line Determination: Identifying the lines of contact that separate high and low-pressure chambers. The quality of these sealing lines directly impacts volumetric efficiency.

- Load Distribution Analysis: Estimating how the transmitted load is shared among the multiple simultaneously engaged tooth pairs in the strain wave gear. This involves solving a statically indeterminate system considering tooth flexibility and the deformation of the flexible ring.

$$ \sum_{i=1}^{N_{eng}} F_i \cdot r_b = T_{load}, \quad \delta_i = \delta_{rigid} + \delta_{flex} + \delta_{bend} $$

where $F_i$ is load on tooth pair $i$, $T_{load}$ is torque, and $\delta_i$ are deformations. - Pumping Chamber Volume Calculation: Computing the change in volume between teeth as a function of rotation angle to derive the theoretical flow rate and ripple characteristics.

$$ dV = \frac{1}{2} \left( \vec{r}_a \times \vec{r}_b \right) \cdot \hat{k} \, d\phi $$

where $\vec{r}_a$ and $\vec{r}_b$ are position vectors to adjacent tooth flanks.

To facilitate these calculations, I often organize key design parameters into a structured table, which serves as an input set for the mathematical model.

| Parameter Group | Symbol | Example Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wave Generator | $a$ (Semi-major axis) | 25.0 | mm |

| $b$ (Semi-minor axis) | 24.5 | mm | |

| Ellipse Ratio ($b/a$) | 0.98 | – | |

| Wave Generator Type | Elliptical Cam | – | |

| Gear Geometry | $z_1$ (Flexible Ring Teeth) | 100 | – |

| $z_2$ (Rigid Ring Teeth) | 102 | – | |

| Module ($m$) | 0.5 | mm | |

| Pressure Angle ($\alpha_0$) | 20° | deg | |

| Profile Shift Coeff. ($x_1$, $x_2$) | +1.2, +1.0 | – | |

| Flexible Ring | Wall Thickness ($e$) | 1.0 | mm |

| Material | Alloy Steel | – | |

| Young’s Modulus | 210 | GPa | |

| Pump | Face Width | 10.0 | mm |

| Nominal Speed | 1500 | rpm |

The mathematical framework I have developed is not merely theoretical. It enables parametric studies to optimize the strain wave gear pump design. For instance, I can investigate the effect of the ellipse ratio ($b/a$) on the magnitude of radial forces and the conformity of tooth engagement. Similarly, the impact of profile shift coefficients ($x_1$, $x_2$) on the shape of the contact pattern and the pump’s displacement per revolution can be quantified. The fundamental advantage of the strain wave gear mechanism—its ability to have many teeth in simultaneous contact—directly benefits the pump by smoothing out flow pulsations compared to traditional gear pumps with only one or two teeth sealing the chambers. The theoretical flow rate $Q_t$ for the strain wave gear pump can be approximated by considering the volume displaced per wave generator revolution:

$$ Q_t = 2 \cdot (z_2 – z_1) \cdot V_{tooth\_chamber} \cdot N $$

where $V_{tooth\_chamber}$ is the average effective volume between a pair of engaged teeth, and $N$ is the speed of the rigid ring. The factor $(z_2 – z_1)$, typically 2 for common strain wave gears, represents the number of wave lobes and is crucial for the pumping action.

In conclusion, my research into tooth profile types and the derivation of precise curve equations provides a comprehensive mathematical foundation for the design and analysis of the strain wave gear pump. By selecting a modified involute profile and rigorously modeling its kinematics within the unique deformed state imposed by the wave generator, I have created tools to engineer a pump that inherently solves the radial force imbalance problem. The strain wave gear pump concept, supported by this detailed analytical framework, promises significant advancements in hydraulic pump technology—offering higher pressure capability, greater reliability, longer service life, and smoother operation. Future work will involve prototyping, experimental validation of the derived profiles, and further optimization of the modification parameters for specific application requirements, solidifying the strain wave gear pump’s role in the next generation of efficient fluid power systems.