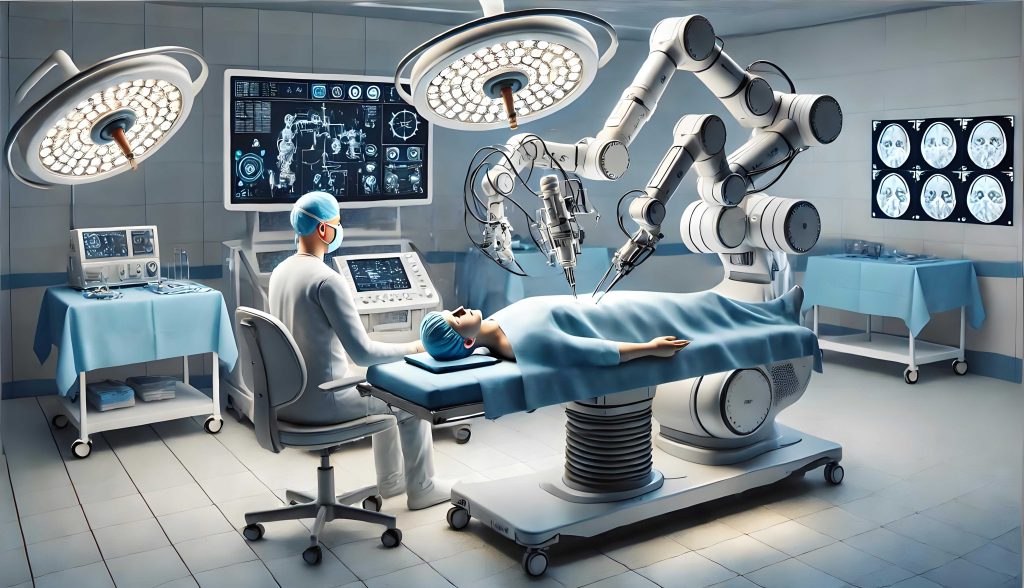

The integration of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) into healthcare represents one of the most transformative technological shifts of our era. At the forefront of this revolution are medical robots—systems that transcend traditional mechanized tools by leveraging machine learning, vast datasets, and sophisticated algorithms to perform tasks ranging from diagnostic analysis and surgical assistance to personalized treatment planning and rehabilitation. As these autonomous systems assume roles once exclusively held by human medical professionals, they promise unprecedented precision, efficiency, and accessibility in care. However, this promise is accompanied by a formidable challenge: determining legal responsibility when a medical robot‘s actions or decisions lead to patient harm. The unique nature of AI-driven autonomy creates profound gaps in existing legal frameworks designed for human actors or simple products. This article explores the intricate landscape of tort liability for medical robot malfunctions and errors, analyzing current regulatory shortcomings and proposing a multi-faceted approach to legal reform that ensures patient safety, fair compensation, and continued innovation.

Defining the “Medical Robot”: Beyond Traditional Instruments

A medical robot in the contemporary context is not merely a programmable arm guided by a surgeon. It is an intelligent system characterized by a degree of operational independence and adaptive learning. Its core functionality can be modeled as a complex interaction between data, algorithms, and physical actuators:

$$ \text{Medical Robot Action} = f(\text{Input Data}, \text{Algorithmic Model } \theta, \text{Environmental State } E) $$

Where the algorithmic model \(\theta\) is continuously updated through machine learning processes, often in ways not fully predictable by its initial programmers. This capacity for “black-box” learning is what distinguishes smart medical robots from conventional medical devices, which operate on fixed, transparent parameters. For legal purposes, we must categorize their functions:

| Function Category | Description | Example | Autonomy Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assistive & Augmentative | Robot provides physical stability, precision, or data visualization, but a human directly controls all critical decisions. | Robotic arm for steadying a surgeon’s hand during microsurgery. | Low |

| Advisory & Diagnostic | Robot analyzes data (e.g., medical images, genomics) and suggests diagnoses or treatment options. The human professional makes the final decision. | AI system analyzing radiology scans for early-stage tumors. | Medium |

| Procedural & Surgical | Robot executes a defined procedure (e.g., suturing, bone cutting) based on pre-operative planning, potentially with real-time adaptation. | Autonomous system performing laser eye surgery or specific steps in a laparoscopic procedure. | Medium-High |

| Fully Autonomous Therapeutic | Robot makes and executes treatment decisions in dynamic, unstructured environments with minimal real-time human oversight. | AI-driven system managing anesthesia delivery or personalized drug infusion rates in an ICU based on continuous patient monitoring. | High |

The legal questions become exponentially more complex as we move down this table toward higher autonomy levels.

The Legal Status of Medical Robots: Person, Product, or Something Else?

A foundational question is whether an advanced medical robot should be granted legal personhood, akin to a corporation. Proponents argue that highly autonomous systems capable of independent learning and decision-making warrant a sui generis “electronic personhood” to bear their own liability. However, this concept faces significant philosophical and practical hurdles. A medical robot lacks consciousness, intentionality, and the capacity to own assets or be deterred by punishment. Granting personhood could inadvertently shield the human designers, manufacturers, and operators from accountability. As one scholar notes, “Liability, like electricity, follows the path of least resistance to a human actor with ‘deep pockets.'” Therefore, the prevailing and most prudent view is that medical robots remain products or tools under the control and for the benefit of human actors (manufacturers, healthcare providers, users). Their actions are ultimately traceable to human choices in design, deployment, and oversight. Thus, tort liability must be channeled through existing or modified doctrines targeting these human entities.

Current Tort Frameworks and Their Inadequacy

Existing law primarily offers two avenues for redress: professional medical malpractice (negligence) and product liability. Both struggle to accommodate the peculiarities of AI-driven medical robots.

1. Medical Malpractice/Negligence

This doctrine holds healthcare providers to a standard of care commensurate with a reasonably skilled professional. The classic formula for negligence is:

$$ \text{Negligence Liability} \iff \text{Duty} + \text{Breach (of Standard of Care)} + \text{Causation} + \text{Damages} $$

When a surgeon uses a medical robot as a tool, traditional rules apply. Liability arises if the surgeon fails to properly train on the system, ignores safety protocols, or misinterprets its outputs. However, what is the “standard of care” when a medical robot operates autonomously? Is it the skill of an average specialist, or the superior accuracy the robot was marketed to provide? Furthermore, causation becomes a nightmare to prove. If an autonomous diagnostic medical robot misses a cancer, was it due to a flaw in its training data, an algorithmic error, an unforeseeable interaction with a rare patient phenotype, or simply an accepted statistical error rate? Disentangling the machine’s “decision” from the human provider’s overarching responsibility is a formidable evidential challenge.

| Scenario | Potential Liable Party | Legal Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Surgeon mispositions a robotic arm, causing injury. | Surgeon/Hospital (Negligence) | Standard causation analysis applies. |

| Robot’s AI recommends an incorrect drug dosage based on flawed data analysis; doctor follows it. | Doctor (Negligence?), Manufacturer (Product Liability?) | Was the doctor negligent to rely on the AI? Was the AI’s error a “defect”? Establishing proximate cause between data flaw and harm. |

| Fully autonomous surgical robot encounters an unforeseen anatomical variation and makes a harmful adaptation not envisioned by programmers. | Manufacturer (Product Liability) | Was the adaptation a “defect” or an intelligent, albeit harmful, response? Does the “state-of-the-art” defense apply? |

2. Product Liability

This strict liability doctrine holds manufacturers responsible for injuries caused by defects in their products, regardless of fault. A medical robot can be defective in three ways:

- Manufacturing Defect: The individual unit deviates from its intended design. (e.g., a faulty sensor).

- Design Defect: The entire product line is unreasonably dangerous. The classic tests are:

- Consumer Expectation Test: Is the product more dangerous than an ordinary consumer would expect?

- Risk-Utility Test: Do the risks of the design outweigh its benefits? Formally, a design is defective if: $$ \sum \text{Forseeable Risks} > \sum (\text{Utility} + \text{Cost of Safer Alternative}) $$

- Warning/Instruction Defect: Inadequate warnings about risks or instructions for safe use.

For medical robots, the design defect category is the most contentious. How do we assess the “risk-utility” of a self-learning algorithm? Its utility may be immense, but its risks are potentially opaque and evolving. The “state-of-the-art” defense, which absolves manufacturers if a danger was not scientifically knowable at the time of sale, could stifle accountability for inherently unpredictable AI behavior. Furthermore, the “defect” may reside not in the hardware or core software, but in the data used to train the AI, leading to biased or inaccurate outputs. Is biased training data a design defect? Traditional product law is ill-equipped to answer this.

The Core Challenges of Attributing Liability

Several specific hurdles make applying traditional tort law to medical robot incidents particularly difficult.

A. The Causation Conundrum: Proving that a specific flaw in a medical robot‘s complex system (algorithm, data, hardware integration) was the proximate cause of harm is a monumental task. The system’s opacity (“black box” problem) means even the manufacturer may struggle to explain why a particular output was generated. This violates a basic premise of tort law: the ability to identify a causal chain.

B. The Learning Gap and Foreseeability: A medical robot that learns from real-world data may evolve in unforeseeable ways. If it develops a harmful “strategy” not present during testing, can the manufacturer be held liable for an “unforeseeable” risk? This clashes with the negligence requirement of foreseeability and the product liability defenses related to unknowable dangers.

C. The Allocation Problem: When harm results from a chain of events involving a medical robot, how is liability apportioned among the various actors? Consider this simplified liability share model for a diagnostic error:

$$ L_{\text{total}} = \alpha L_{\text{manufacturer}} + \beta L_{\text{hospital}} + \gamma L_{\text{doctor}} + \delta L_{\text{data provider}} $$

where \( \alpha + \beta + \gamma + \delta = 1 \). Quantifying \( \alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta \) is currently a judicial impossibility due to evidentiary barriers.

D. Regulatory Lag: The pace of innovation in medical robot technology far outstrips the development of safety standards, certification protocols, and regulatory guidelines. This creates a legal vacuum where it is unclear what constitutes a “reasonable” design or a “proper” standard of care for using such systems.

Proposals for a Reformed Legal and Regulatory Framework

To address these challenges, a multi-pronged approach is necessary, blending adaptations of existing law with new, targeted mechanisms.

1. A Tiered Liability Model Based on Autonomy

Liability rules should be calibrated to the autonomy level of the medical robot.

| Autonomy Level | Primary Liability Basis | Key Legal Modification |

|---|---|---|

| Low (Assistive) | Medical Malpractice (Negligence of user). | None. Traditional rules apply. |

| Medium (Advisory) | Hybrid: Medical Malpractice for unreasonable reliance on AI advice; Product Liability for grossly erroneous advice. | Establish clear standards for “reasonable reliance” by professionals. |

| High (Procedural/Autonomous) | Strict Liability for the Manufacturer, modeled on “Abnormally Dangerous Activity” or enterprise liability. | Shift burden of proof on causation to manufacturer. Apply a “risk-utility” test focused on the system’s overall safety record, not just the specific flaw. |

For high-autonomy systems, framing them as an “abnormally dangerous activity” (similar to keeping wild animals or using explosives) is apt. They offer great social utility but pose a significant and unavoidable risk of serious harm, even with all due care. This justifies imposing strict liability on the entity (the manufacturer) that introduces and profits from this risk.

2. Enhanced Duties for Manufacturers: Explainability and Audit Trails

The law must impose affirmative duties on medical robot manufacturers to mitigate the “black box” problem.

- Duty of Explainability: Manufacturers should be required to implement and maintain technical means to explain, in human-understandable terms, the primary factors leading to a medical robot‘s significant decision. This doesn’t require revealing proprietary algorithms but must provide actionable insight (e.g., “The diagnosis was prioritized due to patterns X, Y, Z in the scan, with confidence C”).

- Mandatory Audit Trails: Every significant action and decision by a medical robot must be logged in a secure, immutable audit trail. This includes input data, system state, the decision/output, and the explainability report. This creates critical evidence for post-incident analysis.

Failure to provide a sufficient audit trail or explanation when harm occurs should result in a rebuttable presumption of defect and causation against the manufacturer.

3. A Mandatory Insurance and Compensation Fund Scheme

Strict liability, while ensuring victim compensation, could stifle innovation if manufacturers face existential financial risk from a single accident. A layered financial responsibility system is needed.

| Layer | Mechanism | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Layer 1: Mandatory Product Liability Insurance | Manufacturers must secure insurance covering potential damages from their medical robots, up to a statutory limit. | Ensures immediate compensation for victims and spreads risk across the insurance market. |

| Layer 2: A Collective Compensation Fund | Funded by a small levy on the sale or lease of each medical robot. Managed by an independent body. | Covers damages that exceed insurance limits or in cases where liability is unclear but compensation is morally warranted (a “no-fault” cushion). |

| Layer 3: Manufacturer’s Residual Liability | Manufacturer remains liable for damages above the combined coverage of Layer 1 & 2, subject to bankruptcy law. | Maintains ultimate financial responsibility and deterrent effect. |

The fund mechanism can be modeled as a dynamic pool:

$$ F_t = F_{t-1} + \sum_{i=1}^{n} (k \cdot S_i) – \sum_{j=1}^{m} C_j $$

where \(F_t\) is the fund at time \(t\), \(k\) is the levy rate, \(S_i\) is the sale price of the i-th medical robot, and \(C_j\) are compensation payouts.

4. Proactive Regulation: Certification and Dynamic Standards

Pre-market certification for medical robots must go beyond hardware safety to include algorithmic audits, bias testing in training data, and validation of explainability features. Standards should be dynamic, requiring periodic re-certification based on real-world performance data (a “learning system” requires a “learning regulation” approach). A central registry for all deployed medical robots, linked to incident reports, would facilitate epidemiology-style safety monitoring.

Conclusion

The advent of intelligent medical robots is not a fleeting trend but a fundamental shift in healthcare delivery. The associated legal challenges are equally profound and cannot be solved by forcing square pegs into the round holes of 20th-century tort law. A coherent response requires recognizing high-autonomy medical robots as a distinct source of risk warranting a strict liability regime for their creators. This must be coupled with legal mandates for transparency (explainability and audit trails) to overcome evidentiary barriers. Finally, a robust financial framework combining mandatory insurance and a collective compensation fund is essential to ensure that victims are made whole without crippling the innovators who drive this promising field forward. By implementing such a balanced, forward-looking framework, society can harness the tremendous benefits of medical robots while confidently managing the unique legal risks they present. The goal is a system where technology advances not in a legal vacuum, but within a structure that prioritizes patient safety, justice, and sustainable innovation.