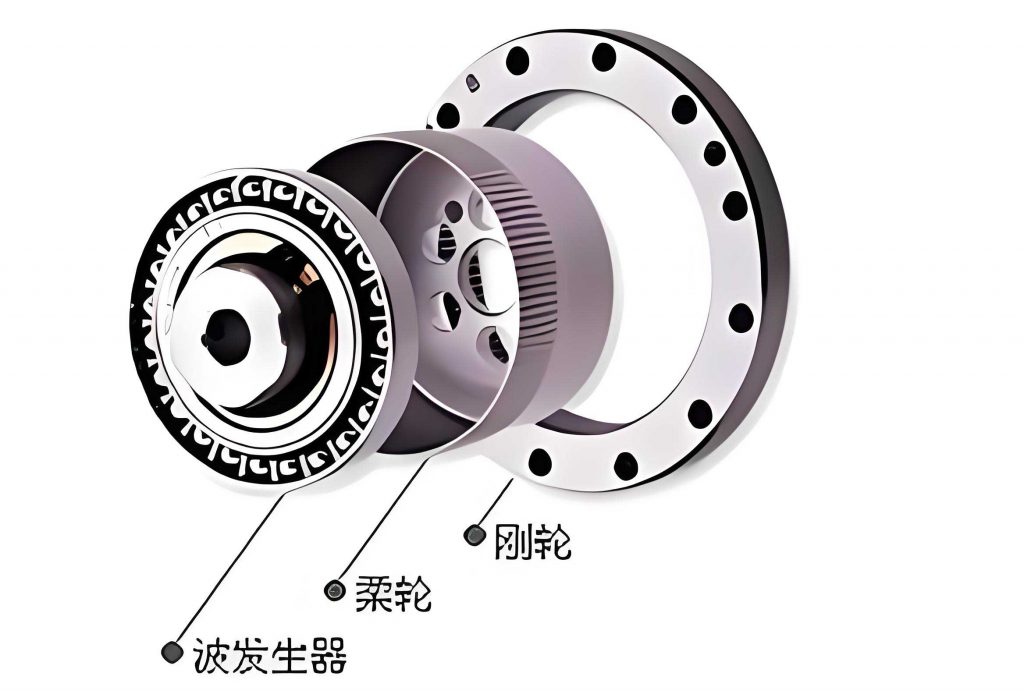

In the realm of precision mechanical transmissions, the strain wave gear system represents a significant advancement, particularly for applications requiring high reduction ratios and substantial power delivery. This transmission mechanism, which integrates concepts from harmonic drives and movable tooth systems, offers a novel approach to overcoming limitations in traditional gear designs. As we delve into the intricacies of this system, it becomes evident that optimizing the tooth surfaces is crucial for minimizing dynamic impacts and ensuring operational stability. This article explores a method for modifying the tooth surfaces using quadratic curves, providing a foundation for designing and manufacturing efficient strain wave gear systems. Throughout this discussion, the term “strain wave gear” will be emphasized to highlight its relevance in modern engineering contexts.

The strain wave gear transmission operates through two primary meshing pairs: one between the wave generator and the rear end of the movable teeth, and another between the front end of the movable teeth and the end-face gear. These pairs facilitate motion conversion, enabling high torque and precise speed reduction. However, a critical issue arises from the kinematic behavior of the movable teeth. When the wave generator acts as the driving component and the end-face gear as the driven component, with the slot wheel fixed, the movable teeth undergo axial reciprocating motion. At the crest or root of the wave generator’s teeth, the velocity of the movable teeth abruptly reverses, leading to theoretically infinite acceleration. This results in severe inertial shocks that can compromise the integrity and performance of the entire strain wave gear assembly. To mitigate this, tooth surface modification is essential to smooth out velocity transitions and reduce impact forces.

Various modification techniques exist, such as circular arcs, sinusoidal surfaces, or quadratic curves. In this work, we adopt quadratic curve transitions for modifying the tooth surfaces of the wave generator, end-face gear, and both ends of the movable teeth. This approach not only simplifies design and manufacturing but also ensures smooth kinematic profiles. The modification involves deriving mathematical equations for the transition curves, ensuring continuity and differentiability at the boundaries with the theoretical tooth surfaces. By applying quadratic functions, we can achieve gradual velocity changes, thereby enhancing the durability and efficiency of the strain wave gear system.

To begin, consider the meshing pair between the wave generator and the rear end of the movable teeth. The theoretical tooth surfaces are based on multi-start Archimedean helicoids with straight generatrices perpendicular to the axis of rotation. For modification, we focus on the crest and root regions of the wave generator. When unfolded on a cylindrical surface of radius \(r\), the transition curve at the wave generator’s crest can be represented in a coordinate system where the \(\xi\)-axis aligns with the circumferential direction and the \(z\)-axis with the axial direction. Let the quadratic curve equation be \(z = f(\xi) = a\xi^2 + b\xi + c\), with parameters \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) determined by boundary conditions. At the modification start point \(-\xi_0\) and end point \(\xi_0\), the curve must match the height and slope of the theoretical surface. The slope \(k_0\) is given by \(k_0 = \tan \theta = hU / (\pi r)\), where \(h\) is the lead of the wave generator, \(U\) is the number of waves, and \(\theta\) is the lead angle. The conditions are:

$$

f(\xi_0) = 0, \quad f(-\xi_0) = 0, \quad f'(\xi_0) = -k_0, \quad f'(-\xi_0) = k_0.

$$

Solving these yields \(a = -k_0/(2\xi_0)\), \(b = 0\), and \(c = k_0 \xi_0 / 2\). Thus, the equation becomes:

$$

z = f(\xi) = -\frac{k_0}{2\xi_0} \xi^2 + \frac{k_0 \xi_0}{2}.

$$

Since \(\xi_0 = h_{W1}/k_0\), where \(h_{W1}\) is the crest modification height, and substituting \(k_0 = hU/(\pi r)\), we obtain:

$$

z = f(\xi) = -\frac{h^2 U^2}{2\pi^2 h_{W1} r^2} \xi^2 + \frac{h_{W1}}{2}.

$$

Expressing in terms of the angular coordinate \(\phi_{W1}\) (the wave generator’s rotation relative to the crest position), with \(\xi = r \phi_{W1}\), the curve on the cylindrical surface is:

$$

z = f_1(\phi_{W1}) = -\frac{h^2 U^2}{2\pi^2 h_{W1}} \phi_{W1}^2 + \frac{h_{W1}}{2}.

$$

This equation is independent of radius \(r\), meaning the surface formed by these curves has constant axial height at the same angle across different radii. Similarly, for the rear end of the movable teeth, the quadratic curve is derived to ensure contact with the wave generator’s crest. After coordinate transformations and considering relative motion, the axial displacement \(\Delta z_{W1}\) imparted by the wave generator’s crest to the movable teeth’s rear end is found to be:

$$

\Delta z_{W1} = \frac{h^2 U^2}{2\pi^2 (h_{W1} + h_1)} \Delta \phi_{W1}^2,

$$

where \(h_1\) is the modification height of the movable teeth’s rear end.

For the wave generator’s root modification, a similar approach is taken. In a local coordinate system, the quadratic curve equation is:

$$

z’ = f(\phi_{W2}) = \frac{h^2 U^2}{2\pi^2 h_{W2}} \phi_{W2}^2 – \frac{h_{W2}}{2},

$$

where \(\phi_{W2}\) is the angular position relative to the root, and \(h_{W2}\) is the root modification height. The corresponding axial displacement \(\Delta z_{W2}\) is:

$$

\Delta z_{W2} = \frac{h^2 U^2}{2\pi^2 (h_{W2} – h_1)} \Delta \phi_{W2}^2.

$$

Turning to the meshing pair between the end-face gear and the front end of the movable teeth, analogous modifications are applied. For the end-face gear’s root, the quadratic curve is:

$$

z = f_1(\phi_{E2}) = -\frac{h^2 Z_E^2}{2\pi^2 h_{E2}} \phi_{E2}^2 + \frac{h_{E2}}{2},

$$

where \(\phi_{E2}\) is the end-face gear’s rotation relative to its root, \(Z_E\) is the number of teeth on the end-face gear, and \(h_{E2}\) is the root modification height. The axial displacement \(\Delta z_{E2}\) is:

$$

\Delta z_{E2} = \frac{h^2 Z_E^2}{2\pi^2 (h_{E2} – h_2)} \Delta \phi_{E2}^2,

$$

with \(h_2\) as the modification height of the movable teeth’s front end. For the end-face gear’s crest, the curve is:

$$

z = f(\phi_{E1}) = \frac{h^2 Z_E^2}{2\pi^2 h_{E1}} \phi_{E1}^2 – \frac{h_{E1}}{2},

$$

and the axial displacement \(\Delta z_{E1}\) is:

$$

\Delta z_{E1} = \frac{h^2 Z_E^2}{2\pi^2 (h_{E1} + h_2)} \Delta \phi_{E1}^2.

$$

The modification principles for the strain wave gear system are derived from the requirement that the axial positions of the wave generator and end-face gear remain unchanged in the unmodified regions. This ensures consistent meshing conditions. Specifically, the axial displacement from the wave generator’s crest must equal that from the end-face gear’s root, i.e., \(\Delta z_{W1} = \Delta z_{E2}\). Substituting the expressions and using the transmission ratio \(i_{WE} = Z_E / U\) and the kinematic relation \(\Delta \phi_{W1} = i_{WE} \Delta \phi_{E2}\), we obtain:

$$

h_{E2} = h_{W1} + h_1 + h_2.

$$

Similarly, equating the displacements from the wave generator’s root and the end-face gear’s crest (\(\Delta z_{W2} = \Delta z_{E1}\)) yields:

$$

h_{W2} = h_{E1} + h_1 + h_2.

$$

These relationships dictate the interdependence of modification heights across the components, forming a core design guideline for strain wave gear systems.

To further elucidate the modification process, we can summarize the key equations and parameters in tables. Table 1 outlines the variables used in the derivations, while Table 2 presents the quadratic curve equations for different components. Such tabulations aid in practical implementations and highlight the systematic nature of the strain wave gear modification.

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| \(h\) | Lead of wave generator | mm |

| \(U\) | Number of waves on wave generator | – |

| \(Z_E\) | Number of teeth on end-face gear | – |

| \(r\) | Radius of cylindrical section | mm |

| \(h_{W1}\) | Crest modification height of wave generator | mm |

| \(h_{W2}\) | Root modification height of wave generator | mm |

| \(h_{E1}\) | Crest modification height of end-face gear | mm |

| \(h_{E2}\) | Root modification height of end-face gear | mm |

| \(h_1\) | Modification height of movable teeth rear end | mm |

| \(h_2\) | Modification height of movable teeth front end | mm |

| \(\theta\) | Lead angle | rad |

| \(k_0\) | Slope of theoretical surface | – |

| \(\phi_{W1}\) | Wave generator angle relative to crest | rad |

| \(\phi_{W2}\) | Wave generator angle relative to root | rad |

| \(\phi_{E1}\) | End-face gear angle relative to crest | rad |

| \(\phi_{E2}\) | End-face gear angle relative to root | rad |

| \(\Delta z\) | Axial displacement | mm |

| \(\Delta \phi\) | Angular increment | rad |

| Component | Curve Equation | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Wave generator crest | $$z = -\frac{h^2 U^2}{2\pi^2 h_{W1}} \phi_{W1}^2 + \frac{h_{W1}}{2}$$ | \(\phi_{W1} \in [-\phi_0, \phi_0]\) |

| Wave generator root | $$z’ = \frac{h^2 U^2}{2\pi^2 h_{W2}} \phi_{W2}^2 – \frac{h_{W2}}{2}$$ | \(\phi_{W2} \in [-\phi_0, \phi_0]\) |

| End-face gear root | $$z = -\frac{h^2 Z_E^2}{2\pi^2 h_{E2}} \phi_{E2}^2 + \frac{h_{E2}}{2}$$ | \(\phi_{E2} \in [-\phi_0, \phi_0]\) |

| End-face gear crest | $$z = \frac{h^2 Z_E^2}{2\pi^2 h_{E1}} \phi_{E1}^2 – \frac{h_{E1}}{2}$$ | \(\phi_{E1} \in [-\phi_0, \phi_0]\) |

| Movable teeth rear end | $$z = \frac{h^2 U^2}{2\pi^2 h_1} \phi_{W1}^2 + \frac{h_{W1}}{2}$$ | Contact with wave generator crest |

| Movable teeth front end | $$z = -\frac{h^2 Z_E^2}{2\pi^2 h_2} \phi_{E2}^2 + \frac{h_{E2}}{2}$$ | Contact with end-face gear root |

The modification methodology not only addresses kinematic shocks but also enhances the load distribution and longevity of strain wave gear systems. By implementing quadratic curves, we achieve smooth transitions that reduce stress concentrations and wear. This is particularly beneficial for high-power applications where traditional strain wave gears might face limitations. Moreover, the derived principles facilitate standardized design processes, allowing engineers to calculate modification heights efficiently based on gear parameters.

In practical terms, the strain wave gear modification involves several steps: first, determining the theoretical tooth surfaces based on the Archimedean spiral; second, identifying the modification regions at crests and roots; third, applying the quadratic equations with appropriate boundary conditions; and fourth, verifying the meshing through kinematic simulations. Computational tools can automate this process, integrating the equations into CAD software for precise manufacturing. The use of quadratic curves is advantageous due to their simplicity and ease of machining, as they can be produced using standard CNC techniques.

Furthermore, the strain wave gear system’s performance can be optimized by adjusting modification heights. For instance, increasing \(h_{W1}\) and \(h_{E2}\) can further smooth velocity transitions but may affect the gear’s compactness. Thus, a balance must be struck based on application requirements. Experimental validations, such as dynamometer tests, can correlate modification parameters with noise reduction and efficiency gains. These aspects underscore the importance of tooth surface modification in advancing strain wave gear technology.

Another consideration is the material selection for strain wave gear components. High-strength alloys or composites can complement the modification by withstanding cyclic loads. Additionally, lubrication plays a role in minimizing friction at modified surfaces. The quadratic curve profile, with its continuous curvature, promotes better oil film formation compared to sharp edges. This holistic approach—combining geometric modification with material science—propels the strain wave gear toward broader industrial adoption.

From a theoretical perspective, the modification principles align with elastohydrodynamic lubrication theory, where smooth surfaces reduce pressure peaks. The quadratic curves approximate optimal profiles for minimizing contact stresses in rolling-sliding interfaces, common in strain wave gear meshing. Future research could explore higher-order polynomials or adaptive curves tailored to dynamic loads. However, the quadratic method remains a robust starting point due to its analytical tractability and practical feasibility.

In conclusion, tooth surface modification via quadratic curves is a viable and effective strategy for enhancing strain wave gear systems. The derived equations and principles provide a framework for designing meshing pairs that mitigate inertial shocks and improve operational smoothness. The interdependence of modification heights ensures kinematic consistency, while the mathematical formulations lend themselves to straightforward implementation. As strain wave gear technology evolves, such modifications will be integral to achieving higher power densities and reliability, solidifying their role in modern mechanical transmissions. The continuous emphasis on strain wave gear in this discussion highlights its significance as a transformative innovation in gear engineering.