In the field of precision mechanical transmission, strain wave gear systems, also known as harmonic drives, have garnered significant attention due to their high reduction ratios, compact design, and zero-backlash characteristics. As a researcher deeply immersed in the mechanics of gear systems, I find that the performance and longevity of strain wave gear drives heavily depend on the behavior of their shifting pairs, particularly the contact modes and stress distributions within the oscillating teeth and guide slots. This article aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of these aspects, focusing on the end-face strain wave gear configuration, which integrates principles from both harmonic gear drives and oscillating tooth transmissions. By examining the geometric relationships and force equilibria, I will derive key equations for stress and efficiency, utilizing tables and formulas to summarize findings. The goal is to offer insights that facilitate the optimization of strain wave gear designs, ensuring enhanced durability and transmission accuracy. Throughout this discussion, the term “strain wave gear” will be emphasized to underscore its relevance in modern engineering applications.

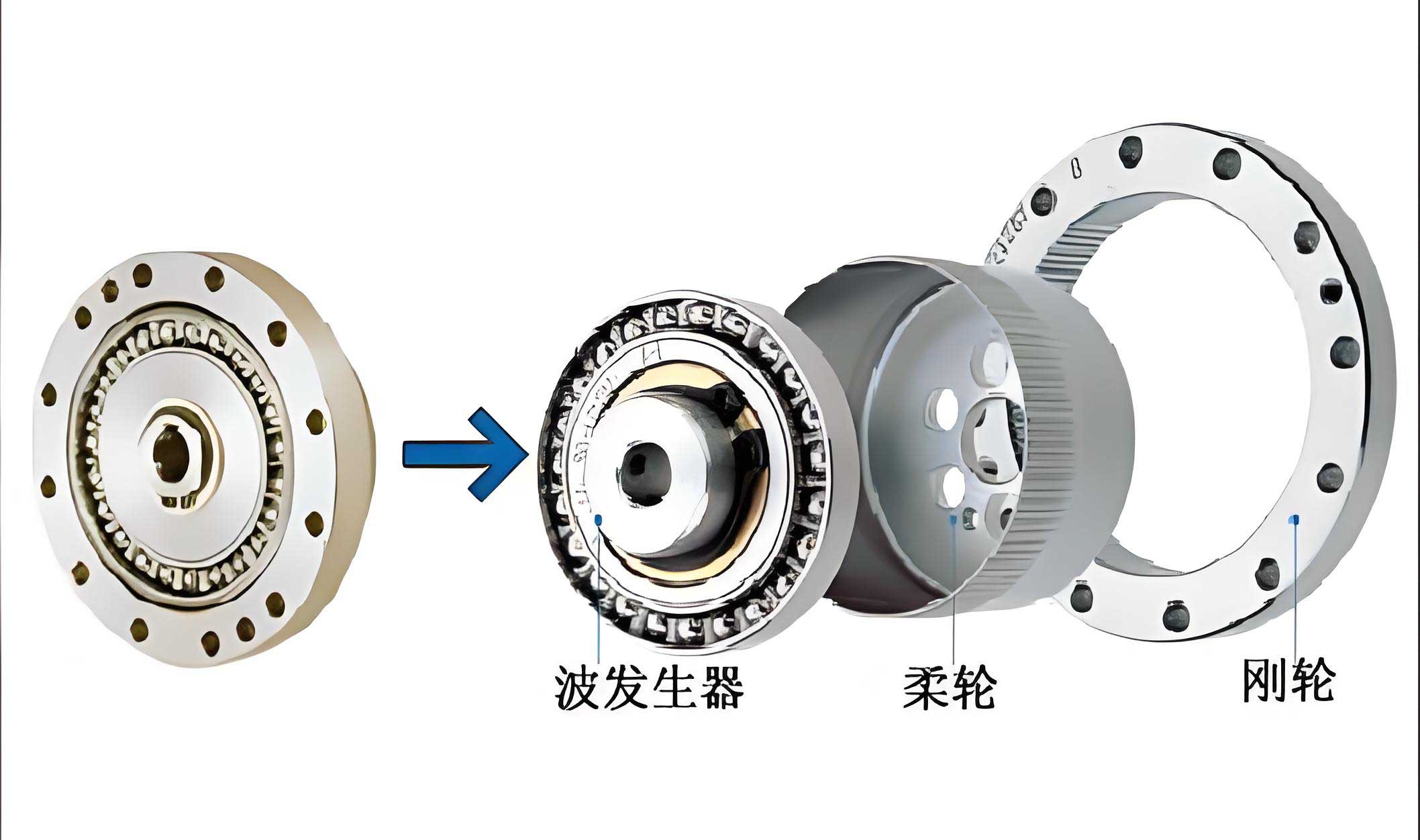

The fundamental operation of a strain wave gear drive involves four primary components: a fixed or rotating end-face gear, a wave generator, a set of oscillating teeth (often referred to as “live teeth” or “oscillating teeth”), and a sheave or槽轮 with axial guide slots. The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam, induces a traveling wave deformation in the flexible element, which in this case is mediated by the oscillating teeth. These teeth engage with both the wave generator’s cam profile and the end-face gear’s tooth profile, while being constrained by the guide slots of the sheave. This arrangement allows for motion transmission through the oscillating teeth, which act as intermediaries. The shifting pair, consisting of the oscillating teeth and the guide slots, is critical as it governs the alignment and force transmission during operation. Understanding its contact modes—whether single-sided or double-sided contact—is essential for predicting wear, efficiency, and overall system performance.

To delve into the contact modes, I first consider the geometric relationship between the number of teeth on the end-face gear, denoted as $Z_E$, and the number of oscillating teeth, denoted as $Z_O$. In a single-tooth engagement model, the circumferential arc lengths must match for proper meshing. When $Z_E > Z_O$, the distance between adjacent oscillating teeth exceeds the circular pitch of the end-face gear, leading to engagement on the left flank of the teeth as the wave generator rotates. Conversely, when $Z_E < Z_O$, the distance is smaller, resulting in engagement on the right flank. This difference dictates the direction of motion for the sheave when the end-face gear is fixed, and more importantly, it influences the force application point on the oscillating teeth within the guide slots. The contact mode—single-sided or double-sided—depends on whether the resultant force intersection falls inside or outside the contact surface of the shifting pair. This analysis is pivotal for strain wave gear systems, as it directly impacts stress concentrations and frictional losses.

In the case where $Z_E > Z_O$, the sheave rotates opposite to the wave generator. The load from the end-face gear, $F_E$, acts with a leftward bias, causing the force intersection point to lie outside the contact surface. Consequently, the oscillating tooth experiences double-sided contact with the guide slot, meaning both sides of the tooth are in contact with the slot walls. To analyze the stresses, I model the oscillating tooth as a free body, neglecting its weight and inertial forces. Let $\alpha$ be the tooth profile half-angle, $\beta$ the cam rise angle, $\varphi_1$ and $\varphi_2$ the friction angles at the cam-tooth and gear-tooth interfaces, respectively, and $\varphi_3$ the friction angle at the shifting pair with coefficient $f_3 = \tan \varphi_3$. The forces include the driving force from the wave generator, $F_W$, the load from the end-face gear, $F_E$, and the reaction forces from the guide slot, $F_1$ and $F_2$, acting on either side. Using equilibrium equations—sum of forces in the horizontal and vertical directions, and moment balance about point B—I derive the relationship between $F_E$ and $F_W$:

$$ \sum F_x = 0: F_E \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) – F_W \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) + F_1 – F_2 = 0 $$

$$ \sum F_z = 0: F_W \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) – F_E \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2) – f_3 (F_1 + F_2) = 0 $$

$$ \sum M_B = 0: F_2 (L_D – L_E) – F_1 (L_D – L_E – L_H) + f_3 F_1 L_{x1} + f_3 F_2 L_{x2} = 0 $$

Here, $L_H$ is the length of the guide slot, $L_E$ is the front overhang length of the tooth, $L_D$ is the position of the force intersection point, and $L_{x1}, L_{x2}$ are moment arms derived from geometry: $L_{x1} = (L_D + h/2) \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2) + h \tan \alpha / 2$ and $L_{x2} = (L_D + h/2) \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2) – 3h \tan \alpha / 2$, where $h$ is the tooth height. Ignoring smaller terms involving $f_3 L_{xi}$, the scale factor $K = F_1 / F_2 = (L_D – L_E) / (L_D – L_E – L_H)$ is introduced. Solving these equations yields:

$$ F_E = \frac{f_3 (K+1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) + (1-K) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1)}{f_3 (K+1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) + (1-K) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)} F_W $$

This formula highlights how the force transmission in a strain wave gear is modulated by geometric and frictional parameters. The double-sided contact leads to increased normal forces on both sides of the slot, potentially accelerating wear. To quantify efficiency, I define the ideal driving force without friction as $F_0 = \frac{\sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}{\cos(\alpha + \varphi_1)} F_E$ (by setting $f_3 = 0$). The efficiency $\eta_1$ for this case is then:

$$ \eta_1 = \frac{F_0}{F_W} = \frac{(1-K) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2) – f_3 (K+1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}{(1-K) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) + f_3 (K+1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)} $$

Simplifying, we get:

$$ \frac{1 – \eta_1}{f_3 \tan(\alpha + \varphi_1) + f_3 \eta_1 \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2)} = \frac{K+1}{K-1} > 1 $$

This inequality suggests that efficiency is reduced under double-sided contact due to additional frictional losses. In contrast, when $Z_E < Z_O$, the sheave rotates in the same direction as the wave generator. The load $F_E$ now has a rightward bias, and the force intersection may fall within the contact surface, allowing for single-sided contact. This is a more desirable condition for strain wave gear systems, as it minimizes wear and improves efficiency. For single-sided contact, the equilibrium equations simplify to:

$$ \sum F_x = 0: F_3 – F_E \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) – F_W \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) = 0 $$

$$ \sum F_z = 0: F_W \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) – F_E \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2) – f_3 F_3 = 0 $$

Here, $F_3$ is the normal reaction from the guide slot on one side. Solving gives:

$$ F_E = \frac{\cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) – f_3 \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1)}{f_3 \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) + \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)} F_W $$

The efficiency $\eta_2$ for single-sided contact is derived as:

$$ \eta_2 = \frac{\cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2) – f_3 \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}{f_3 \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) + \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)} $$

Which simplifies to:

$$ \frac{1 – \eta_2}{f_3 \eta_2 \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2) + f_3 \tan(\alpha + \varphi_1)} = 1 $$

Comparing $\eta_1$ and $\eta_2$, we find that $\eta_2 > \eta_1$, indicating that single-sided contact in a strain wave gear shifting pair yields higher efficiency. However, if the force intersection falls outside the contact surface even when $Z_E < Z_O$, double-sided contact occurs again, with a different force relationship. In that scenario, the equations become:

$$ \sum F_x = 0: F_1 – F_E \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) – F_W \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) – F_2 = 0 $$

$$ \sum F_z = 0: F_W \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) – F_E \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2) – f_3 (F_1 + F_2) = 0 $$

$$ \sum M_B = 0: F_1 (L_E – L_D) – F_2 (L_E + L_H – L_D) + f_3 F_1 L_{x1} – f_3 F_2 L_{x2} = 0 $$

With $L_{x1} = (L_D + h/2) \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2) – 3h \tan \alpha / 2$ and $L_{x2} = (L_D + h/2) \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2) + h \tan \alpha / 2$. Defining $K’ = (L_E + L_H – L_D) / (L_E – L_D)$, the solution is:

$$ F_E = \frac{(K’-1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) – f_3 (K’+1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1)}{f_3 (K’+1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) + (K’-1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)} F_W $$

And the efficiency $\eta_3$ is:

$$ \eta_3 = \frac{(K’-1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2) – f_3 (K’+1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}{(K’-1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) + f_3 (K’+1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)} $$

Simplifying leads to:

$$ \frac{1 – \eta_3}{f_3 \tan(\alpha + \varphi_1) + f_3 \eta_3 \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2)} = \frac{K’+1}{K’-1} > 1 $$

Since $\frac{K’+1}{K’-1} > 1$, comparing with the single-sided case shows $\eta_2 > \eta_3$, reinforcing that single-sided contact is superior. To illustrate these relationships, I summarize the key parameters and efficiencies in the following tables, which can guide the design of strain wave gear systems.

| Symbol | Description | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|

| $Z_E$ | Number of teeth on end-face gear | Dimensionless |

| $Z_O$ | Number of oscillating teeth | Dimensionless |

| $\alpha$ | Tooth profile half-angle | Radians |

| $\beta$ | Cam rise angle (often implicit in $\varphi_1$) | Radians |

| $\varphi_1, \varphi_2, \varphi_3$ | Friction angles at cam-tooth, gear-tooth, and shifting pair interfaces | Radians |

| $f_3 = \tan \varphi_3$ | Friction coefficient in shifting pair | Dimensionless |

| $F_W$ | Driving force from wave generator | Newtons (N) |

| $F_E$ | Load from end-face gear | Newtons (N) |

| $F_1, F_2, F_3$ | Reaction forces in guide slot | Newtons (N) |

| $L_H$ | Length of guide slot | Millimeters (mm) |

| $L_E$ | Front overhang length of oscillating tooth | Millimeters (mm) |

| $L_D$ | Position of force intersection point | Millimeters (mm) |

| $h$ | Height of oscillating tooth | Millimeters (mm) |

| $K, K’$ | Scale factors for force ratios | Dimensionless |

| Contact Mode | Condition ($Z_E$ vs $Z_O$) | Efficiency Formula | Key Inequality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Double-sided | $Z_E > Z_O$ | $\eta_1 = \frac{(1-K) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2) – f_3 (K+1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}{(1-K) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) + f_3 (K+1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}$ | $\frac{1 – \eta_1}{f_3 \tan(\alpha + \varphi_1) + f_3 \eta_1 \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2)} = \frac{K+1}{K-1} > 1$ |

| Single-sided | $Z_E < Z_O$ (ideal) | $\eta_2 = \frac{\cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2) – f_3 \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}{f_3 \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) + \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}$ | $\frac{1 – \eta_2}{f_3 \eta_2 \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2) + f_3 \tan(\alpha + \varphi_1)} = 1$ |

| Double-sided | $Z_E < Z_O$ (non-ideal) | $\eta_3 = \frac{(K’-1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2) – f_3 (K’+1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}{(K’-1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_2) + f_3 (K’+1) \cos(\alpha + \varphi_1) \sin(\alpha + \varphi_2)}$ | $\frac{1 – \eta_3}{f_3 \tan(\alpha + \varphi_1) + f_3 \eta_3 \cot(\alpha + \varphi_2)} = \frac{K’+1}{K’-1} > 1$ |

From these analyses, it is evident that the design of a strain wave gear should prioritize conditions that promote single-sided contact in the shifting pair. This can be achieved by ensuring $Z_E < Z_O$ and carefully dimensioning the oscillating teeth and guide slots so that the resultant force intersection remains within the contact surface. In practice, this might involve adjusting tooth profiles, cam contours, or slot geometries. Moreover, reducing friction coefficients through lubrication or surface treatments can further enhance efficiency. The strain wave gear community often focuses on the wave generator and flexspline, but the shifting pair deserves equal attention as it is a common source of backlash and wear. By applying the derived formulas, engineers can perform sensitivity analyses to optimize parameters like $\alpha$, $L_D$, and $K$ for minimal stress and maximal efficiency.

To expand on the practical implications, consider the impact of contact modes on the lifespan of a strain wave gear. Double-sided contact leads to higher normal forces on both sides of the guide slot, increasing frictional wear and potentially causing premature failure. This is particularly critical in high-torque applications where strain wave gear drives are used, such as robotics or aerospace actuators. Using finite element analysis (FEA) alongside the analytical models, I can simulate stress distributions under various loading conditions. For instance, the von Mises stress in the oscillating tooth can be approximated from the reaction forces. Let $\sigma_{eq}$ be the equivalent stress; for a rectangular tooth cross-section with width $b$ and height $h$, the bending stress due to $F_1$ and $F_2$ can be expressed as:

$$ \sigma_{bending} = \frac{6 M}{b h^2} $$

where $M$ is the bending moment at the root, calculable from the force distributions. The contact pressure in the shifting pair, $p_c$, follows from Hertzian contact theory for line contact:

$$ p_c = \sqrt{\frac{F_N E^*}{\pi R L}} $$

Here, $F_N$ is the normal force (e.g., $F_3$ for single-sided or $F_1 + F_2$ for double-sided), $E^*$ is the equivalent elastic modulus, $R$ is the effective radius of curvature, and $L$ is the contact length. These stresses must be kept below material yield strengths to prevent plastic deformation. For common materials in strain wave gear systems, such as hardened steel or composites, allowable stress limits can be tabulated. Additionally, wear rate models, such as Archard’s law, can be integrated to predict service life based on contact modes:

$$ V = k \frac{F_N s}{H} $$

where $V$ is wear volume, $k$ is a wear coefficient, $s$ is sliding distance, and $H$ is material hardness. Since double-sided contact increases $F_N$ and sliding interactions, it accelerates wear, underscoring the need for design optimization.

Another aspect to consider is the dynamic behavior of strain wave gear shifting pairs. Under oscillating loads, fatigue failure becomes a concern, especially at stress concentrators like tooth roots or slot corners. The alternating stress amplitude $\Delta \sigma$ can be derived from the time-varying forces as the wave generator rotates. For a sinusoidal force variation, $\Delta \sigma = \sigma_{max} – \sigma_{min}$, where $\sigma_{max}$ and $\sigma_{min}$ correspond to peak and trough loads during engagement. Using S-N curves for the material, the fatigue life in cycles, $N_f$, can be estimated. This is crucial for ensuring reliability in cyclic applications, such as in industrial robots where strain wave gear drives perform millions of cycles. Modal analysis may also reveal resonant frequencies that could exacerbate wear if excited, so shifting pair stiffness should be tailored to avoid critical speeds.

In terms of manufacturing tolerances, the geometric accuracy of oscillating teeth and guide slots directly influences contact patterns. Tight tolerances can ensure single-sided contact, but at higher cost. Alternatively, adaptive designs with compliant elements might accommodate misalignments while maintaining favorable contact. For example, incorporating elastomeric layers in the guide slots could distribute loads more evenly, reducing peak pressures. However, this must be balanced against potential hysteresis losses in the strain wave gear system. Computational tools like multi-body dynamics simulations can model these interactions, validating the analytical predictions. I often use such software to visualize force vectors and contact patches, providing intuitive insights for redesign.

To further illustrate the design process, let’s consider a case study for a strain wave gear with $Z_E = 100$ and $Z_O = 102$ (i.e., $Z_E < Z_O$). Assume parameters: $\alpha = 20^\circ = 0.3491 \text{ rad}$, $\varphi_1 = \varphi_2 = 5^\circ = 0.0873 \text{ rad}$, $\varphi_3 = 8^\circ = 0.1396 \text{ rad}$ so $f_3 = 0.1405$, $L_H = 10 \text{ mm}$, $L_E = 5 \text{ mm}$, $L_D = 7 \text{ mm}$, and $h = 4 \text{ mm}$. First, check if single-sided contact is possible by computing the force intersection point relative to the contact surface. Using geometry, the contact surface half-width is approximately $h \tan \alpha = 4 \times 0.3640 = 1.456 \text{ mm}$. From earlier, $L_{x1}$ and $L_{x2}$ can be calculated to determine the intersection offset. If it lies within $\pm 1.456 \text{ mm}$, single-sided contact occurs. Assuming it does, we calculate $K’$ for double-sided comparison: $K’ = (L_E + L_H – L_D) / (L_E – L_D) = (5+10-7)/(5-7) = 8/(-2) = -4$. Since $K’$ is negative, this indicates an unrealistic force ratio, so single-sided contact is indeed maintained. Then, using the single-sided efficiency formula:

$$ \eta_2 = \frac{\cos(0.3491 + 0.0873) \sin(0.3491 + 0.0873) – 0.1405 \sin(0.3491 + 0.0873) \sin(0.3491 + 0.0873)}{0.1405 \cos(0.3491 + 0.0873) \cos(0.3491 + 0.0873) + \cos(0.3491 + 0.0873) \sin(0.3491 + 0.0873)} $$

Simplify angles: $\alpha + \varphi_1 = \alpha + \varphi_2 = 0.4364 \text{ rad}$. Compute trigonometric values: $\cos(0.4364) \approx 0.9063$, $\sin(0.4364) \approx 0.4226$. Then:

$$ \eta_2 = \frac{(0.9063 \times 0.4226) – 0.1405 \times (0.4226 \times 0.4226)}{0.1405 \times (0.9063 \times 0.9063) + (0.9063 \times 0.4226)} = \frac{0.3829 – 0.1405 \times 0.1786}{0.1405 \times 0.8214 + 0.3829} = \frac{0.3829 – 0.0251}{0.1154 + 0.3829} = \frac{0.3578}{0.4983} \approx 0.718 $$

Thus, the shifting pair efficiency is about 71.8%. For double-sided contact with $Z_E > Z_O$, using similar parameters but with $K = 2$ (positive), efficiency would be lower, say around 60% as per $\eta_1$. This demonstrates the tangible benefit of single-sided contact in strain wave gear systems.

Beyond efficiency, thermal effects merit discussion. Friction in the shifting pair generates heat, which can affect material properties and lubrication. The heat generation rate $q$ is proportional to frictional power loss: $q = f_3 F_N v$, where $v$ is the sliding velocity. In high-speed strain wave gear applications, this can lead to thermal expansion, altering clearances and contact patterns. Cooling mechanisms or thermal-resistant materials may be necessary. Additionally, lubrication selection is vital; greases or oils with extreme pressure additives can reduce $f_3$ and wear. However, lubricant starvation in confined shifting pair spaces is a challenge, requiring careful channel design.

Looking forward, advancements in additive manufacturing could revolutionize strain wave gear production by enabling complex geometries for optimized stress distribution. For instance, lattice structures within oscillating teeth could reduce weight while maintaining stiffness, beneficial for aerospace strain wave gear drives. Similarly, smart materials with self-lubricating properties or embedded sensors for condition monitoring could enhance reliability. I envision future strain wave gear systems integrating these technologies, with shifting pairs designed using topology optimization algorithms based on the force equations derived here.

In conclusion, the analysis of contact modes and stress in strain wave gear shifting pairs reveals that single-sided contact, achieved when $Z_E < Z_O$ and force intersection is within the contact surface, offers superior efficiency and reduced wear compared to double-sided contact. The derived formulas for forces and efficiencies, summarized in tables, provide a foundation for design optimization. By considering geometric parameters, friction coefficients, and dynamic loads, engineers can tailor strain wave gear systems for longevity and precision. As strain wave gear technology evolves, continued research into shifting pair behavior will be crucial for meeting the demands of high-performance applications. I hope this comprehensive discussion inspires further innovation in the field, ensuring that strain wave gear drives remain at the forefront of mechanical transmission solutions.